The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

To our parents and everyone who has ever supported our movement: this is our thanks to you.

by Amanda Seales

In the late 60s, newspaper headlines and magazines chronicled America bursting into flames as black folks watched great leaders of our community be taken down by oppressive forces. Out of those ashes came the Black Arts Movement and the black pride movement. Dashikis and Afros, mud cloth and black power fist picks, red-black-and-green wristbands and Africa pendants flooded the landscape as black folks reconnected with the inner and outer beauty that they had been taught for so long to despise. Entire communities began to actively teach not only the truth about the African diaspora, but the importance of black hair, its uniqueness, its strength, and its power. A generation finally saw their blackness represented without restraint.

I was fortunate to grow up in the 90s. Hip-hop was becoming a global phenomenon giving identity to all of us with something to say, and styles upon styles to wear; it was pre-TSA and you could see your folks off at the gate at the airport, and most awesomely, as a young black girl I was surrounded by representations of black girl magic. In music, athletics, and television, the 90s saw all different shades and shapes of black women stepping into the light and owning it.

They had all types of hairstyles, fashion flavas, professions, accents, attitudes, and unique attributes. Id watch them and could see myself in them. Id hear them, and find my funny in their comedic genius. Id study their demeanor, their walk, the way they held their champagne glasses, and my young and influential spirit would take it in, process it through my maturing minds mainframe and pieces of each of them would take their place on the strands of my ever-forming identitys DNA. That time of development was incredibly integral to my becoming the black woman I always wanted to be. Outside of my own familial circles, parents, and peer groups, seeing those images of black beauty represented in front of me informed me, from the dawn of my development, that I was worthy, I was valuable, and I could be anything!

For the current generation, TV has been replaced with social media. At its best, social media serves as a place to share and learn new information, find humor, and watch an incredible animal rescue. As a comedian and actress, it has been a great resource for sharing my comedy, like the countdown to the release of my HBO stand-up special, I Be Knowin, behind-the-scenes photos as the character Tiffany DuBois on HBOs Insecure, connecting folks to my black culture comedy game show, Smart Funny & Black, and giving insight on social issues, relationships, and Game of Thrones. Most important, it has been a source point for connecting with various voices that regularly resonate a message of love and empowerment to the black community.

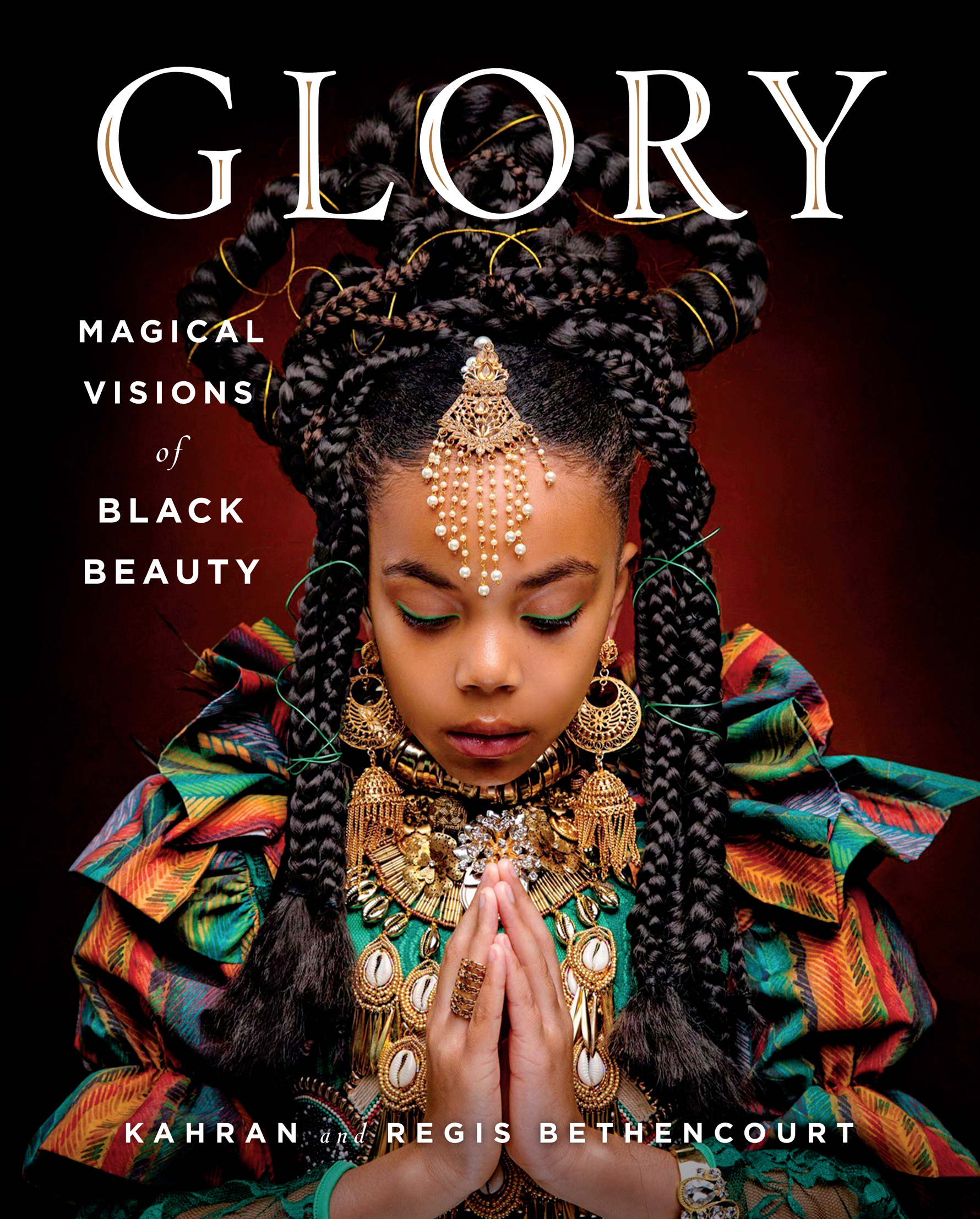

Though there are a number of pages that consistently amplify the gloryfrom the kitchen to baby hairsof the natural black crown, when I first came across the AfroArt series on Instagram, I was mesmerized. The photos were more than just cute captures of adorable kids cheesing beneath meticulously oiled scalps. In their unique and elevated vision, the AfroArt creators had deftly found the natural regal spirit of these beautiful brown children and, with the lens, given it space to illuminate and radiate.

Behind a pointed gaze, with each kink and curl in place, the subjects connect with the viewer. The creativity in their settings and costumes was exceeded only by how both were seamlessly interwoven with the bold hairstyles that framed each magnificent and innocent face. The varied combination of pastoral, couture, jewels, and more continuously expand the possibilities of how we see ourselves as black bodies.

To be young and black in this world can be a dangerous burden of the pressures of having to pursue perfection and duel with discrimination, but in the work of the AfroArt series, we see the embodiment of self-love displayed in portraits of pride and power that lift not only our spirits, but our community, reminding us of our boundless possibilities.

As photographers, we are blessed with the opportunity to capture the stories we want to tell through images. We are literally looking through a lens at our people, and what we see in everyday folks is the beauty of black culture. It is an extraordinary beauty that is rarely represented in its full glory. Often symbolized by our hair, that glory is a halo that radiates up to the heavens and confirms the exquisite grace of its natural state.

We think of ourselves as cultural storytellers, documenting not only the world as we see it, but also imagining the world we want to see. For generations, black culture, black identity, and black hair has often been under-celebrated in the western world. In the past, black kids were often taught that their natural hair was too kinky or nappy, not long enough, not straight enough. Battles on the schoolhouse playground about whether your skin was too dark or too light were a typical occurrence for many, and sadly still are today.

Growing up, Reg and I had vastly different experiences with black culture and black hair. For me, as a black kid in the South it was understood that at a certain age, when my soft and curly baby hair had grown out, it was time to either get a kiddie perm or straighten my hair to manage its kinky texture.

At the age of six, I was introduced to the world of relaxers, which would become my norm for the next twenty-two years. As an adult I began a long journey of not only learning about it, but loving and accepting my hair in its natural state.

The child of a Filipino mother and a black father, Reg grew up with very different experiences. In school, black kids (specifically girls and women) always commented on his good hair. Boys would often make fun of it and chide him for not really being black. Reg often wore hats or had short haircuts to hide his natural curls. Rather than dealing with the confusion surrounding his identity as a mixed-race child, hats and short hair allowed him to blend in.

Today, we are able to channel those experiences into our work. We often imagine our future kids living in a world where their identity is celebrated rather than derided, misunderstood, and misappropriated.

Our journey as photographers began with a love of visual storytelling. We started by documenting our families stories and evolved into the kids fashion industry where we quickly noticed a lack of diversity. At photo shoots, parents often felt the need to straighten their kids natural hair in an attempt to have them fit in.

For decades, images of our childrens subdued selves have traveled out into the world, reaffirming the sense that acceptable black beauty was not our natural beauty. We knew this had to change.