Contents

NATALIE HAYNES

PANDORAS JAR

Women in Greek Myths

For my mum, who has always thought a woman with an axe was more interesting than a princess

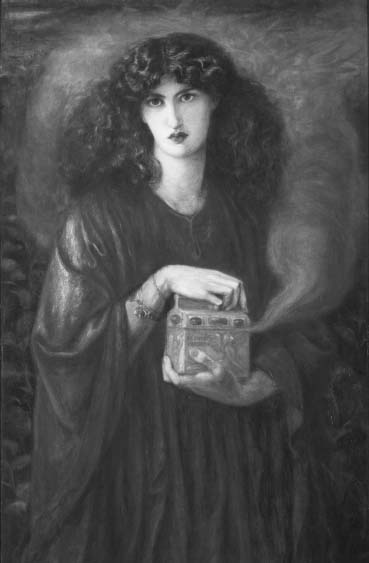

List of Illustrations

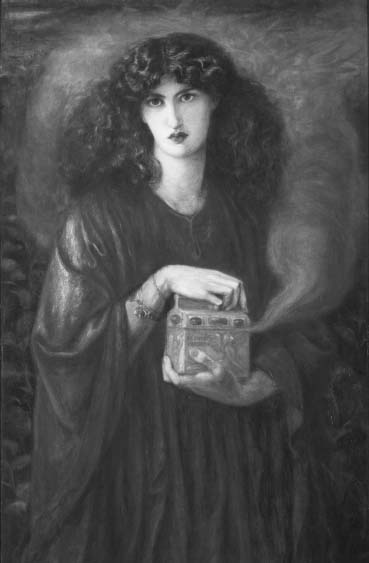

Pandora, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, 1871. (Heritage Image Partnership Ltd / Alamy Stock Photo)

Oedipus Separating from Jocasta, Alexandre Cabanel, 1843. (akg-images)

Pompeian fresco depicting Leda and the Swan. (KONTROLAB / Contributor)

])

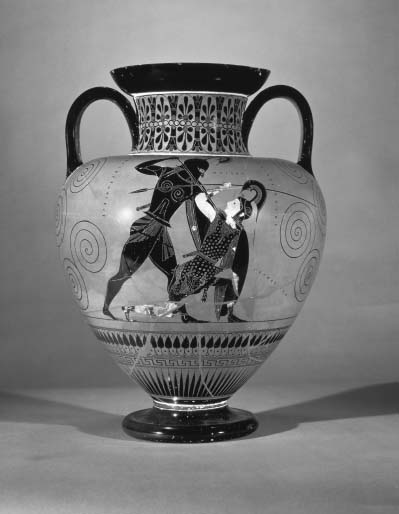

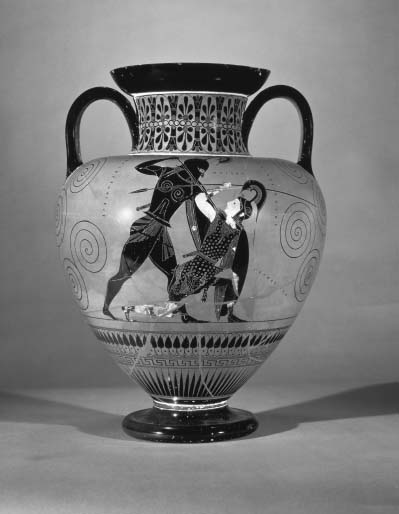

Amphora depicting Achilles driving his spear into Penthesilea, Exekias, fifth century BCE . (De Agostini Picture Library / Bridgeman Images)

A Calyx krater showing Aegisthus killing Agamemnon, Dokimasia Painter, fifth century BCE . (William Francis Warden Fund / Bridgeman Images)

Orpheus and Eurydice, Peter Paul Rubens, 163638. (Bridgeman Images)

Red-figure hydria showing Phaedra on a swing, fifth century BCE . (bpk / Antikensammlung, SMB / Johannes Laurentius)

Lucanian Calyx krater depicting Medea escaping in her chariot, Policoro Painter, 400 BCE. (Leonard C. Hanna, Jr. Fund / Bridgeman Images)

Penelope weaves and waits, Marian Maguire, 2017. (Acrylic on wooden fireplace, 135cm x 139cm x 23cm. Reproduced with permission of the artist)

Introduction

W HEN H ARRY H AMLIN STOOD BEHIND A PILLAR IN THE DARKNESS OF Medusas lair in the Ray Harryhausen film Clash of the Titans, flames flickering off his shield, his face glistening with sweat, my brother and I were transfixed. Perseus holds the shield in front of his eyes to protect himself from Medusas stony gaze. He watches the reflection of a slithering monster, outlined in front of the fire behind him. This Medusa has a lashing, snakish tail as well as the traditional snakes for hair. She is armed with a bow and arrows, and can knock one of Perseus comrades off his feet with a single hit. As the man sprawls on the ground, she glides forward into the light. Suddenly her eyes flash bright green. He is turned to stone where he lies.

Medusa fires another arrow, this time taking Perseus shield out of his hands. Her rattlesnake tail quivers in anticipation of the kill. Perseus tries to catch her reflection in the glinting blade of his sword as she nocks a third arrow. Medusa inches closer as Perseus waits, turning his sword in his hand. The sweat has formed beads across his upper lip. At the crucial moment, he swings his arm and decapitates her. Her body writhes before thick red blood seeps out from her neck. When it reaches his shield, there is a hissing sound as it corrodes the metal.

This film along with Jason and the Argonauts was a staple of my childhood viewing: it was a rare school holiday when one of them wasnt on TV. It did not occur to me that there was anything unusual about the depiction of Medusa, because she wasnt a character, she was just a monster. Who feels sorry for a creature who has snakes for hair, and turns innocent men to stone?

I would go on to study Greek at school because of these films, and probably also because of the childrens versions of Greek myths I had read (a Puffin edition, I think, by Roger Lancelyn Green. My brother tells me we had a Norse one too). It would be years before I came across any other version of Medusas story, anything that told me how she became a monster, or why. During my degree, I kept coming across details in the work of ancient authors which were quite different from the versions I knew from simplified stories Id read and watched. Medusa wasnt always a monster, Helen of Troy wasnt always an adulterer, Pandora wasnt ever a villain. Even characters that were outright villainous Medea, Clytemnestra, Phaedra were often far more nuanced than they first appeared. In my final year at college, I wrote my dissertation on women who kill children in Greek tragedy.

I have spent the last few years writing novels which tell stories from Greek myth that have largely been forgotten. Female characters were often central figures in ancient versions of these stories. The playwright Euripides wrote eight tragedies about the Trojan War which survive to us today. One of them, Orestes, has a male title character. The other seven have women as their titles: Andromache, Electra, Hecabe, Helen, Iphigenia in Aulis, Iphigenia Among the Taureans and TheTrojan Women. When I began hunting out the stories I wanted to tell, I felt exactly like Perseus in the Harryhausen movie: squinting at reflections in the half-light. These women were hiding in plain sight, in the pages of Ovid and Euripides. They were painted on vases which are held in museums all over the world. They were in fragments of lost poems, and broken statues. But they were there.

It was, however, while debating the character of a non-Greek woman that I decided to write this book. I was on Radio 3, discussing the role of Dido, the Phoenician queen who founded the city of Carthage. To me, Dido was a tragic heroine, self-denying, courageous, heartbroken. To my interviewer, she was a vicious schemer. I was responding to her in Virgils Aeneid, he was responding to her in Marlowes Dido, Queen of Carthage. Id spent so long thinking about ancient sources Id forgotten that most people get their classics from much more modern sources (Marlowe is modern to classicists). Dismal though I think the film Troy to be, for example, it has probably been seen by more people than have read the Iliad.

So I decided I would choose ten women whose stories have been told and retold in paintings, plays, films, operas, musicals and more and I would show how differently they were viewed in the ancient world. How major female characters in Ovid would become non-existent Hollywood wives in twenty-first-century cinema. How artists would recreate Helen to reflect the ideals of beauty of their own time, and we would lose track of the clever, funny, sometimes frightening woman that she is in Homer and Euripides. And how some modern writers and artists were finding these women, just like I was, and putting them back at the heart of the story.

Every myth contains multiple timelines within itself: the time in which it is set, the time it is first told, and every retelling afterwards. Myths may be the home of the miraculous, but they are also mirrors of us. Which version of a story we choose to tell, which characters we place in the foreground, which ones we allow to fade into the shadows: these reflect both the teller and the reader, as much as they show the characters of the myth. We have made space in our storytelling to rediscover women who have been lost or forgotten. They are not villains, victims, wives and monsters: they are people.

PANDORA

JOCASTA

HELEN

MEDUSA

THE AMAZONS