Richard A. Peterson

Creating Country Music

Fabricating Authenticity

The University of Chicago Press

Chicago and London

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

1997 by The University of Chicago

All rights reserved. Published 1997

Printed in the United States of America

16 15 14 13 12 11 10 3 4 5

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-66284-8 (cloth)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-66285-5 (paper)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-11144-5 (e-book)

ISBN-10: 0-226-66284-5 (cloth)

ISBN-10: 0-226-66285-3 (paper)

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Peterson, Richard A.

Creating country music : fabricating authenticity / Richard A. Peterson.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-226-66284-5 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-226-11144-5 (e-book)

1. Country musicHistory and criticism. 2. Popular cultureUnited States. I. Title.

ML3524.P48 1997

781.64209dc21

97-9675

CIP

MN

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.

Dedicated to Edna Wildman Peterson, Mom

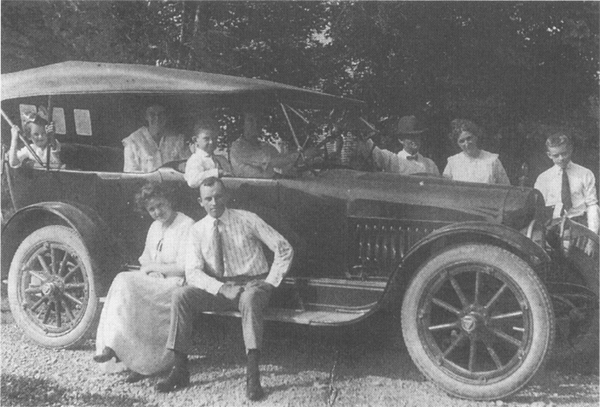

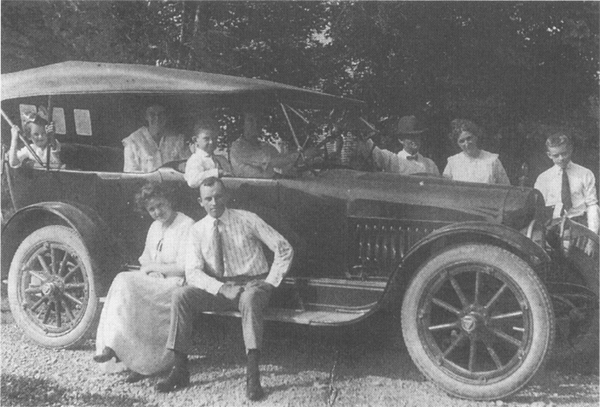

Edna Wildman Peterson on the running board of the family Hudson with her parents (behind the hood of the car) and six of her siblings in 1917

Acknowledgments

A NOTE ON METHOD

My first memory of country music was as a small city-kid listening to a barn-dance program while visiting my grandfathers farm near Selma in Clark County, Ohio. I was puzzled at all the hilarity of those at the barn-dance because I usually couldnt tell what they were laughing about. I was fascinated, however, by the way the harmonica player simulated all the sounds of hounds and men on a coon hunt. I also loved the yarns the old hired man Earl Doster would tell as we rode along on a horse-drawn feed wagon or side-delivery rake. The stories were generally about the goings-on of men and beasts deep in the hills and hollers of his home, Ken-tuck. Earl, I later learned from Mother, was a hillikan of the kind that our kind avoided. But on those dusty 1940 summer days Earl sang playful rhymes while spitting tobacco for emphasis, as we rumbled along.

As a teen I was back working a summer on the farm. My kin were Quakers so there wasnt much music, but I found a bunch of records in an old wind-up Victrola stored in the abandoned tenant house near the cattle barn that reeked of coal oil, rodent droppings, and the sheeps wool stored there. I remember plaintive ballads, bluesy numbers, foxtrots, fiddle tunes, and comedy numbers. A committed New Orleans jazzrevivalist at the time, the only disk I kept was one by the Memphis Jug Band, but in all likelihood, I was listening to some Jimmie Rodgers records the year that Hank Williams died.

In the years following I became an industrial sociologist and, thanks in part to the promptings of a graduate student, Alan Orenstein, at the University of Wisconsin, and with another student, David Berger, whom I met there, I began to research aspects of the music industry. But it wasnt until some years after taking a job at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tennessee, that I became aware that the center of country music production was just six blocks from the Vanderbilt campus. Certainly my university colleagues didnt consider anything having to do with country as relevant to those of our kind. But already by then a seasoned researcher of aspects of jazz, pop, and rock, I cared little about the elitist snobbery of my university colleagues of the 1970s.

While researching popular music producers and session musicians, the organizing question for the country music research became Why Nashville? Why should the production of country music be located in a regional center (rather than in L.A. and New York like the rest of commercial music), and why should that center be located in Nashville rather than Dallas, Atlanta, Bakersfield, Chicago, Cincinnatior Richmond, Indiana, for that matter, where many early records were made? The easy answer, of course, was that the Grand Ole Opry was located in Nashville, but that answer just begged further questions. Why, for example, did the Opry flourish when the other larger and more important barn-dance programs of the 1930s floundered and disappeared one by one?

No single method has proved adequate to answer the questions, and so over the past twenty-five years I have made numerous interviews; I have attended concerts, recording sessions, and TV program tapings; I have consulted newspaper, company, and scholarly archives; I have made secondary analyses of available data in sources ranging from fan magazines to government surveys; and I have learned much from the rapidly growing number of detailed reports on specific artists, local scenes, and genres of country musicmany completed since my quest began. Publishing bits and pieces of the work over the years has facilitated feedback from knowledgeable informants and scholars. This work also helped to put into sharper focus what I still did not understand. Giving lectures to elder-hostel groups and academic scholars, as well as teaching undergraduate seminars on country music, has greatly helped to render the huge complex of facts and speculations down to a set of ideas that can more readily be grasped and played with.

I profoundly appreciate the many people who have shared their ideas, their knowledge, and above all their enthusiasm for what is now called country music. The first was Don Light, the veteran Nashville talent agency director who, though bemused by my naivete, made it his mission to edify me. He took me backstage at the Ryman to meet Bill Monroe and to experience the chemistry of the Opry up close while Monroe, Porter Wagoner, Dotty West, and others were performing. He introduced me to Jimmie Buffett and arranged for me to spend four days on the road touring the Midwest with the Oak Ridge Boys when they were still a gospel music group and Tony Brown was their piano player.

At the Grand Ole Opry I met and extensively interviewed Bud Wendell, who was then the manager. Don also introduced me to Ronnie Light, who was then a staff record producer at RCA. Through Ronnie I attended a number of recording sessions and got to see Chet Atkins, Skeeter Davis, Waylon Jennings, Charlie Pride, and Hank Snow, among others, at work in the studio. Harold Bradley, one of the premier session guitarists, showed me something of the range of styles he had at his command, and I observed the magical manipulations of sound that were at the fingertips of the staff engineers.

It is not so much that I learned directly about the details of early country music from these people or from the brief periods of consulting with Jack Clement, Tandy Rice, Film House, and the trade magazines Billboard and Radio & Records. As with my two years of working at country musics huge annual fan-oriented bonanza, Fanfare, I gained something of a sense of what country music was and is about.

Just living in Nashville since the mid-1960s has been a great advantage for this project because I have run across a large number of profoundly important informants in the normal course of daily activities. Just two examples will have to suffice. I met one of my first informants, John DeWitt, through the Yacht Club. As a Vanderbilt engineering student, Jack had helped to build the original transmitter for WSM, home of the Grand Ole Opry, and by 1952 he was WSMs general manager when Hank Williams was fired off the Opry. The most recently found informant was Marjorie Kirby, whose late husband, Edward Kirby, was the director of publicity for WSM in the 1930s. With her husband, Marjorie helped to found the early fan magazine,

Next page

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.