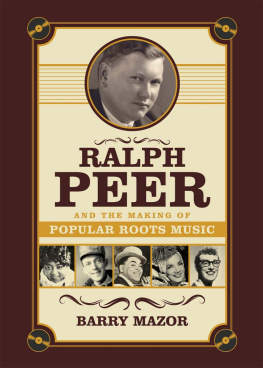

Copyright 2015 by Barry Mazor and Southern Music Publishing Co., Inc.

All rights reserved

Published by Chicago Review Press, Incorporated

814 North Franklin Street

Chicago, Illinois 60610

ISBN 978-1-61374-021-7

All photos are courtesy of the Peer Family Archives unless otherwise indicated.

The Storms Are on the Ocean by A. P. Carter

Copyright 1927 by Peer International Corporation

Copyright renewed. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Mazor, Barry.

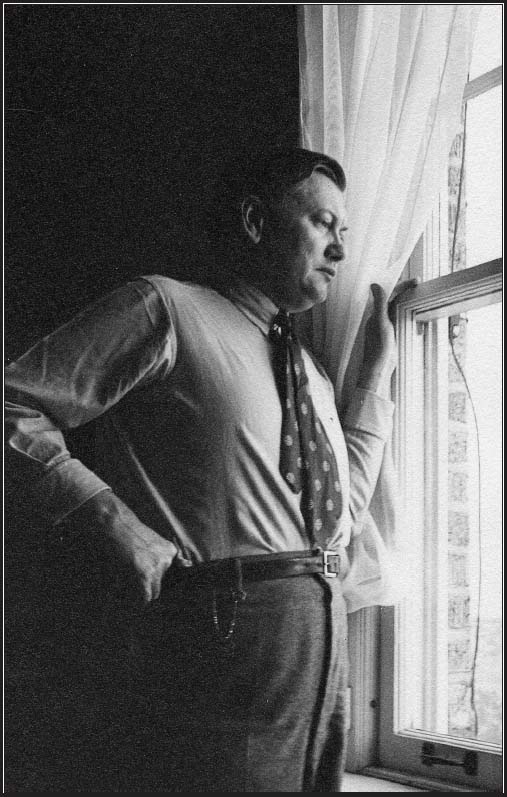

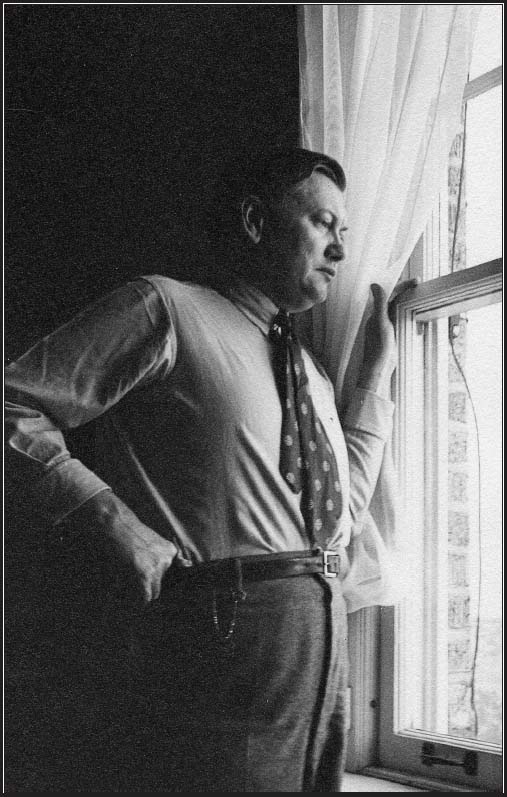

Ralph Peer and the making of popular roots music / Barry Mazor.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-61374-021-7

1. Peer, Ralph Sylvester, 18921960. 2. Sound recording executives and producersUnited StatesBiography. 3. Sound recording industryUnited StatesBiography. I. Title.

ML429.P37M39 2014

781.64092dc23

[B]

2014029263

Interior design: Jonathan Hahn

Printed in the United States of America

5 4 3 2 1

Contents

I NDEX

Introduction

Something NewBuilt Along the Same Lines

I N 1955 FOLKLORIST J OHN G REENWAY sent a letter to the celebrated A&R man and music publisher Ralph S. Peer, pressing him to assess his own impact on American music over the previous thirty-five years or sospecifically, on folk music. Peer answered Professor Greenway directly and succinctly, in an unpublished letter that, in its thrust, must have taken the protest song chronicler by surprise:

As a pioneer in this field, I perhaps set the pattern which has resulted in a really tremendous new section of the Amusement Industry. I quickly discovered that people buying records were not especially interested in hearing standard or folkloric music. What they wanted was something newbuilt along the same lines.

It was perfectly characteristic of Peer that his response concerned what appealed to people buying recordsconsumers of commercial, popular music. He had never been driven by any particular desire to contribute something to traditional music, by any musical theory or ideology, by any sense that it was good to make or sell some flavor of music rather than some other, or even by his personal taste, but by decades of mounting practical experience about what evoked a positive audience response, provoked it again and again. Finding an untapped opportunity that workedan audience unaddressed, a style of music underexplored, a new way to freshen what was already availablewas precisely what excited Ralph Peer, spurred him to musical and music business experimentation, as the discovery of some new reaction or interaction might galvanize an applied scientist. His music-changing experiments proceeded for some fifty years, with enormous consequences.

Ralph Peer developed and executed a business strategy that bordered on an aesthetic. At its core was a simple idea: untapped roots musicmusic that evidences rich history, that has moved a specific people of some distinctive place and culture and reflects their lives and rhythmscould appeal to much broader audiences by far, if handled properly as a commercial musical proposition. He never, of course, referred to the arena he was commercializing and popularizing as roots music, as we commonly do now; he died at the dawn of the 1960s, and nobody used the term in his day. But he talked about local music, regional music, and occasionally traditional or standard or even legendary music. He knew what he was after.

Before very long, so did the industry he worked in. Step-by-step, he was entrusted with exploring and developing more and more popular music derived from the range commonly included under the roots music umbrella today. In the twenty-first century, we can take it for granted that theres a rooted side to pop, at times more in favor, at times less so, but it remains an available direction for popular music to take. That wasnt always so, and it wasnt inevitable that it would be.

When the business of creating, promoting, and selling music on a mass scale first took hold, published sheet music was the medium, and its use by professionals in performances was the key to getting the music widely known, so their musically literate audiences might want to buy and play it, tooat home, in a school band, or perhaps semiprofessionally, at a wedding or some community band shell or restaurant. Focused that way, the music business hardly concerned itself with artists or songwriters with little or no formal training, or who specialized in some regionally favored music less known and less appreciated outside of its limited home base, music most typically favored by those who didnt read music at all, music apparently without universal commercial pop prospects as they understood them. The early music publishers and professional concert and show producers of the Tin Pan Alley era saw music outside of the Broadway, concert hall, and broadest parlor sheet-music mainstream as marginal propositions, and as a consequence, the structure of the industry they built across the Western world marginalized it still further, without giving the matter much thought.

Surprisingly, perhaps, that didnt change even when recording arrived at the end of the nineteenth century, when making something out of music that hadnt been composed or appeared as sheet music became so very much easier. If anyone, even then, saw broader potential or musical power in the down-home roots music being skipped over so cavalierly, they certainly werent doing anything about it.

In the United States, the excluded, underestimated, marginalized music included all but the most schooled music made by African Americans, virtually all music of rural and small-town white Southerners other than hymnal lyric sheets, and while there had already been, in Jelly Roll Mortons famous description, a Spanish tinge detectable in American popular music for many years, Latino music, and Latin American songs, werent going to cross the border into American parlors or stages, either.

And then Ralph Peer came along. He saw as much potential in passed-over, underexplored, professionally neglected music, and did as much to make something of it, as any one person ever has. He knew that no working idea in the music business could stay unexplored by others for long, and didnt put much stock in great-man theories, as was amply evident when, late in life, he was asked directly whether the popularizing of roots musics various flavors would have happened without him.

I do think that if I hadnt, somebody else would have, he answered. There was a bigger demand for [those] records, and theyd eventually give them the artists they wanted.

And maybe sobut eventually can take a long time. Ralph Peer made it happen the way it happened. He virtually always, as he put it himself, looked first for music that was local in nature, precisely because it would be novel everywhere else. He was not a musicologist, or a performer, or a composer, but a modernizing businessman, a record man and a music publisher, and it was as a businessman that he pulled the lever that budged the musical world. It tookand, even in this interconnected age, still takesa music industry structure equipped to convey and promote untapped music for us even to be aware of it. Because Peer opened the music businesss door to unheard regional music and implemented some serious ideas about what to do with it, the very structure of the industry evolved, and so did the sounds audiences could hear. Durable genres with musical power and lasting, growing enterprises developed, and pop music broadened in the United States and around the world.

Next page