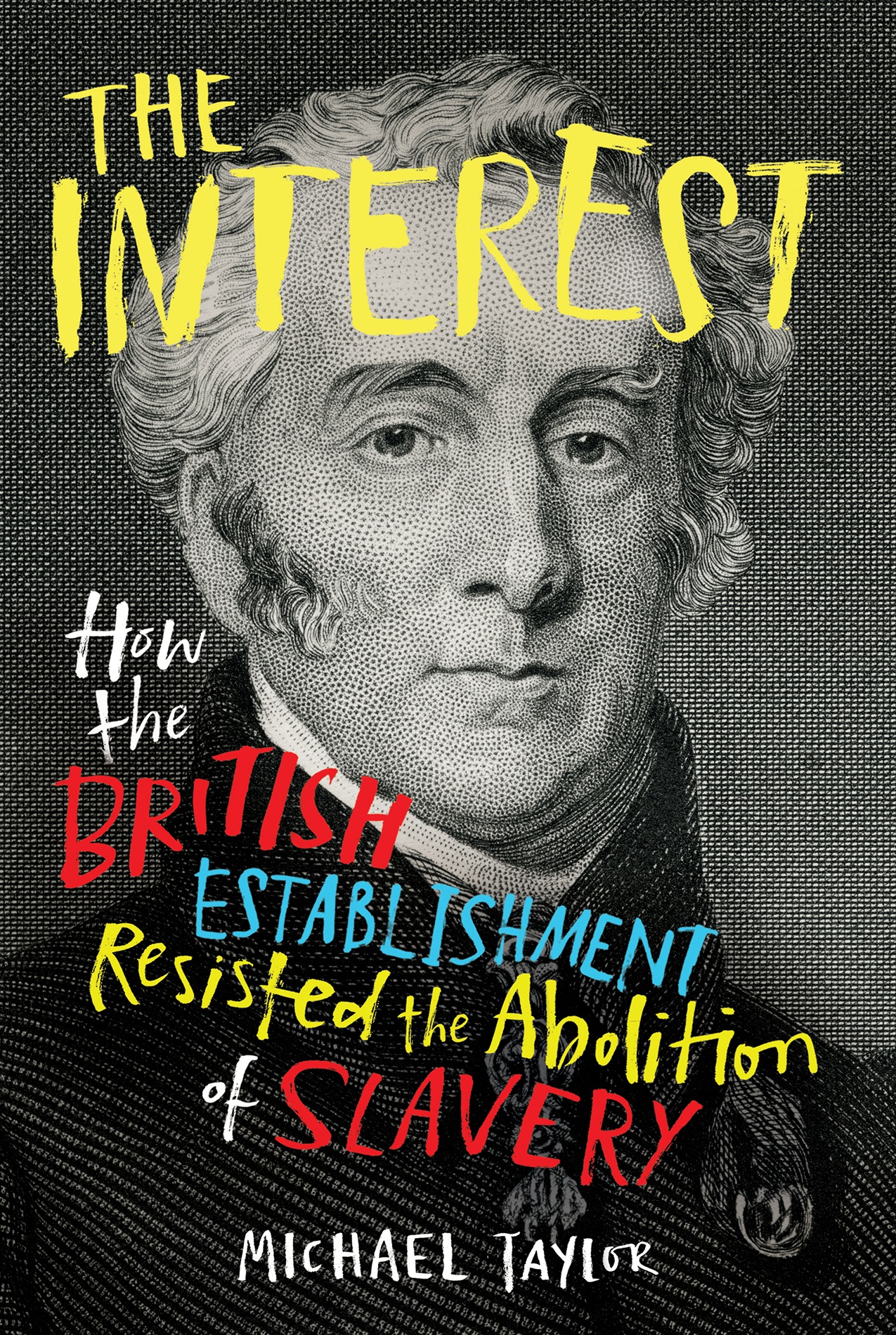

Michael Taylor - The Interest: How The British Establishment Resisted The Abolition Of Slavery

Here you can read online Michael Taylor - The Interest: How The British Establishment Resisted The Abolition Of Slavery full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. publisher: Penguin Books Ltd, genre: Art. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The Interest: How The British Establishment Resisted The Abolition Of Slavery

- Author:

- Publisher:Penguin Books Ltd

- Genre:

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Interest: How The British Establishment Resisted The Abolition Of Slavery: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Interest: How The British Establishment Resisted The Abolition Of Slavery" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

The Interest: How The British Establishment Resisted The Abolition Of Slavery — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Interest: How The British Establishment Resisted The Abolition Of Slavery" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Michael Taylor is an historian of colonial slavery, the British Empire and the British Isles. He graduated with a double first in history from the University of Cambridge, where he earned his PhD and also won University Challenge. He has since been Lecturer in Modern British History at Balliol College, Oxford, and he is currently a Visiting Fellow at the British Librarys Eccles Centre for American Studies.

To my parents, Hubert and Geraldine.

All maps Bill Donohoe 2020. The following images are the following organisations and individuals and/or reproduced with their permission:

First picture section:

Courtesy of the John Carter Brown Library.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Courtesy of the Henry Lillie Pearce Fund, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London, Michael Graham-Stewart Slavery Collection. Acquired with the assistance of the Heritage Lottery Fund.

Hakewill, A Picturesque Tour of the Island of Jamaica (London, 1825).

William Clark, Ten Views of the Island of Antigua (London, 1823). Courtesy of the John Carter Brown Library.

Reproduced in John Saunders, Portraits and Memoirs of Eminent Living Political Reformers (London, 1840).

Courtesy of Wilberforce House, Hull City Museums and Art Galleries / Bridgeman Images.

Frontispiece of Macaulay, Life and Letters (1900).

National Portrait Gallery, London.

Courtesy of the John Carter Brown Library.

Metropolitan Museum of Art. The Elisha Whittelsey Collection, The Elisha Whittelsey Fund, 1959.

Ickworth House, Suffolk / Bridgeman Images.

PLA Collection / Museum of London.

Courtesy of The Baring Archive.

Copyright of Philip Mould Ltd / Bridgeman Images.

Courtesy of the Council for World Mission / SOAS Library.

Elizabeth Heyrick, Immediate not Gradual Emancipation [1824] (Philadelphia, 1836).

Papers relative to the Wesleyan Mission, 31 (March 1828).

Second picture section:

Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

The Ohio State University, Billy Ireland Cartoon Library and Museum.

Courtesy of University of Glasgow Library, Archives & Special Collections.

National Portrait Gallery, London.

Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

. Out of copyright..

Bristol Museum & Art Gallery / Bridgeman Images.

Courtesy of the State Library of Victoria.

National Portrait Gallery, London.

Courtesy of the Birmingham Museum & Art Gallery.

Wikimedia Commons.

National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London. Gift of the Executors of Mr and Mrs F H Boxer.

Courtesy of the Birmingham Museum & Art Gallery.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

National Portrait Gallery, London.

public domain.

Michael Graham-Stewart / Bridgeman Images.

Shortly before 4.00 p.m. on 29 September 2015, the private plane carrying David Cameron and his retinue touched down at Norman Manley International Airport outside Kingston, Jamaica. As the prime minister disembarked, he was greeted with a red carpet,

For almost 200 years, Jamaica had been the largest and most valuable slave colony in the British Empire, and by the early nineteenth century there were more enslaved people in Jamaica over 300,000 than there were people of any description in any British city except London. Some of the legacies of this history are obvious. Jamaicas three counties are Surrey, Middlesex, and Cornwall, while the islands parishes include Manchester and Westmoreland; Sabina Park in Kingston is one of the great crucibles of cricket; and the tripartite structure of the Jamaican government is modelled on Westminster. There are also pointed, personal aspects to these shared histories, for many Jamaicans of the present day are descended from the Africans whom the British had enslaved and trafficked across the Atlantic, their surnames often taken from the slaveholders who once owned their ancestors. At the same time, many Britons have ancestors among those slaveholders, and Camerons visit had brought one in particular to public attention. Sir James Duff was an army officer and MP who, as the trustee of a Jamaican estate, had received compensation for 202 enslaved people. Duff was also Camerons first cousin six times removed.

In the weeks and months before Cameron went to Jamaica, he had faced mounting calls to atone [and] apologise personally and on behalf of his country for the horrors of colonial slavery. The Barbadian historian Sir Hilary Beckles asked him to acknowledge responsibility for your share of this situation and to contribute in a joint programme of rehabilitation and renewal. Earlier that year the Jamaican Parliament had unanimously passed a motion which stated that the country was entitled to reparations for colonial slavery, and now Professor Verene Shepherd, the chair of Jamaicas National Commission on Reparations, declared that nothing short of an unambiguous apology would suffice. Then, shortly after Camerons plane touched down at Kingston, Portia Simpson-Miller raised the issues of slavery and reparatory justice during their bilateral talks. It followed that, on 30 September, when Cameron finally addressed the assembled dignitaries in the Jamaican Parliament, he would indeed speak of slavery and the long, dark shadow that it cast over the Caribbean. But he did not say sorry.

Instead, Cameron appeared to represent Britain as a fellow victim of slavery. Describing Britons and Jamaicans as friends who have gone through so much together since those darkest of times, he urged his audience to move on from this painful legacy and continue to build for the future. And while Cameron allowed that slavery was abhorrent in all its forms and without a place whatsoever in any civilised society, the traditional, triumphalist account of Britains connection to colonial slavery shone through. Britain is proud, he told the descendants of the very people whom the British had enslaved, to have eventually led the way in its abolition.

The lack of apology should not have been surprising. On the day before Camerons speech, Downing Street had defended the British governments stubborn refusal to discuss reparations. Slavery was centuries old, a spokesman said, and it happened under a different government. It therefore remained official policy that the right approach did not encompass reparations. On the contrary, the right approach appeared to involve spending 25 million on a new prison outside Kingston for the purpose of incarcerating Jamaican nationals who had been convicted of crimes in Britain. Downing Street promptly issued another press release: UK signs deal, ran the headline, to send Jamaican prisoners home. Notably, all this occurred while Theresa Mays Home Office was aggressively pursuing the deportation of Windrush-generation West Indians.

In his 732-page memoir, For the Record, David Cameron found no space for his 2015 trip to Jamaica, or the issue of historical slavery more generally. However, the

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The Interest: How The British Establishment Resisted The Abolition Of Slavery»

Look at similar books to The Interest: How The British Establishment Resisted The Abolition Of Slavery. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Interest: How The British Establishment Resisted The Abolition Of Slavery and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.