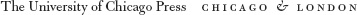

Cruelty and Laughter

Cruelty and Laughter

FORGOTTEN COMIC LITERATURE AND THE UNSENTIMENTAL EIGHTEENTH CENTURY

Simon Dickie

SIMON DICKIE is associate professor of English at the University of Toronto.

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

2011 by The University of Chicago

All rights reserved. Published 2011.

Printed in the United States of America

20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 11 1 2 3 4 5

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-14618-8 (cloth)

ISBN-10: 0-226-14618-9 (cloth)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-14620-1 (e-book)

The University of Chicago Press gratefully acknowledges the generous support of the University of Toronto toward the publication of this book.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Dickie, Simon.

Cruelty and laughter : forgotten comic literature and the unsentimental Eighteenth Century / Simon Dickie.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-14618-8 (hardcover : alk. paper)

ISBN-10: 0-226-14618-9 (hardcover : alk. paper) 1. English wit and humor18th centuryHistory and Criticism. 2. Cruelty in literature. I. Title.

PR935.D53 2011

827.509dc22

2011004069

This paper meets the requirements of ansi/niso z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

For N.H.A.

ILLUSTRATIONS

PREFACE

This book has three aims. First, I bring to light a vast but little-known archive of eighteenth-century comic texts, from pamphlets and short-lived periodicals to jestbooks, verse miscellanies, farces, variety shows, and comic fiction. Mainly from the three decades 174070, these texts seem almost oblivious to the humanitarian sensibilities we have come to associate with this period. Second, I contest some prevailing tendencies in eighteenth-century studiesthe interpretive habits that have kept this archive at the margins of scholarly inquiry. These include the routine treatment of this period as a moment of transition to modernity, and the related emphasis on politeness, sentimentalism, and other middle-class values. Third, I offer literary scholars an expanded understanding of some major authors, including Gay, Goldsmith, Aphra Behn, Charlotte Lennox, Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, Richardson, Smollett, Sarah Fielding, Burney, Austen, and Sterne. I devote a central chapter to Henry Fielding, the midcentury author who most urgently engages with contemporary debates about the fragility of sympathy and the dubious joys of laughter.

The raw material of this book will often be distasteful, if not repugnant, to modern readers. Yet these texts reach out to us from such an alien world, and preserve such unfamiliar idioms, that it seemed crucial to quote freely from them rather than reviewing the evidence in more detached ways. For the same reason, I have retained eighteenth-century terminologies in place of preferred modern usages: cripple, hunchback, dwarf rather than the currently preferred little person; deaf rather than person with deafness. Fat, ugly, hag, cuckold: the brutal directness of such words itself tells us a lot about this world of feeling. Both the primary texts and this books approach to them raise troubling questions. How should abhorrent aspects of the past be written about? Who should or shouldnt do it? Should they be discussed at all? However these questions are answered, the evidence itself remains, and it wont go away.

NOTE ON PRIMARY SOURCES, QUOTATIONS, AND REFERENCES

Primary sources are quoted exactly as they appearwith all eighteenth-century spellings, capitalization, contractions, and word division. Since it would occur multiple times on every page, I have foregone all use of sic. With more canonical texts, unmodernized editions have been used wherever possible (the Florida Sterne, Donald Bonds Spectator, Halsband and Grundys editions of Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, etc.).

In light of recent arguments for the expressive significance of nonstandard punctuation, and because so many of these texts were produced to be read aloud, I have strived to approximate details of layout and typography. Of particular importance to this project, I have retained all italics. Punch lines are often set in italic type, and italic is everywhere used to point up ironies or innuendos that might otherwise be lost on modern readers. This practice, while never consistent, became especially clear in nonliterary sources like newspapers and the Old Bailey Sessions Papers, examined in . One of the few disappointments of the Old Bailey digitization project is its romanization of all italic type; citations to this source have been verified against the originals. Unless explicitly identified as mine, all italic text in primary-source quotations is original.

Jestbooks and comic pamphlets are notoriously fugitive texts. They were messily and haphazardly produced. Large numbers give no date in the imprint, and their publishers used all the most artful puffing techniques, including wildly inflated edition numbers. Ongoing work at the English Short Title Catalogue (ESTC) is now revealing the extent and diversity of bibliographic guesswork that went on as these books entered collections around the world. Even with easier access to newspaper advertisements and book trade data, it has not always been possible to establish firm publication dates or confirm edition numbers. Perhaps half the relevant ESTC dates are conjectural, many of them derived from the old British Museum Catalogue of Printed Books and now repeated in Eighteenth Century Collections Online (ECCO). I have used none of these estimates without external confirmation. Occasional corrections to ESTC are made silently, and noticeably suspect edition numbers are given in quotation marks. In several cases, it seemed preferable to specify the actual copy consulted.

French and Spanish comic texts are all quoted from contemporary translations: Urquhart and Motteuxs Rabelais, Motteuxs Cervantes (the odious Motteux translation, as Samuel Putnam described it), Tom Browns Scarron, and contemporary versions of Quevdo, Guzmn, and Lazarillo de Tormes. For all their defects as translations, these were the versions that midcentury authors read and emulated. Biblical quotations are from the King James Version; quotations from Greek and Latin are from Loeb Classical Library editions. With dates before 1753, January 1 is taken as the beginning of the year.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

It would be impossible to thank everyonecolleagues, students, librarians, and archivistswho has helped me with this book. My largest debts are to my Stanford mentors. Terry Castle first pointed me toward the forgotten byways of eighteenth-century culture and taught me more about writing than she can ever know. John Bender has been energetically involved with this project since the beginning; I can only hope that the finished product rewards his hopes. Without the example and encouragement of Hans-Ulrich Gumbrecht, I would never have plunged so deeply into a single historical moment. Also at Stanford, I owe many valuable insights to W. B. Carnochan, Maureen Harkin, and Suvir Kaul. The most scholarly of librarians, William McPheron was also an unrivaled critic of academic prose.

This paper meets the requirements of ansi/niso z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ansi/niso z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).