Suppose a Sentence

BRIAN DILLON

New York Review Books New York

New York Review Books New York

This is a New York Review Book

published by The New York Review of Books

435 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014

www.nyrb.com

Copyright 2020 Brian Dillon

All rights reserved.

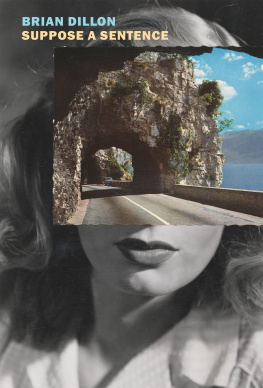

Cover art: John Stezaker, Mask XCI, 2009, collage. Courtesy of the artist, The Approach Gallery, London, and private collection, New York; photographer: Alex Delfanne.

Cover design: Katy Homans

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Dillon, Brian, 1969 author.

Title: Suppose a sentence / Brian Dillon.

Description: New York City: New York Review Books, 2020.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020011251 (print) | LCCN 2020011252 (ebook) | ISBN 9781681375243 (paperback) | ISBN 9781681375250 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Literary style. | English languageRhetoric. | English languageSentences. | Creation (Literary, artistic, etc.)

Classification: LCC PN203 . D55 2020 (print) | LCC PN203 (ebook) | DDC 808/.042dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020011251

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020011252

ISBN: 978-1-68137-525-0

v1.0

For a complete list of titles, visit www.nyrb.com or write to:

Catalog Requests, NYRB, 435 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014

For Emily LaBarge

Contents

Sensibility as Structure

O r maybe a short sentence after all, a fragment in fact, a simple cry, of pain or pleasure, or succession of same, of the same cries that is, compounded, and spoken at the last, in extremis, or another sort of beast entirely, whose unmeaning cry is just an overture, before the sentence sets in distinguished motion its several parallel clauses, as though it were a creature with at least four legs (Every sentence was once an animal, says Emerson), so slowly but deliberately intent on its progress, so stately in its procession, so lavish in attention to the world it passes through, so exacting in the concentration it demands in turn, thatwhat?here already the sentence swerves, and although you are sure youve caught the sense the shape has begun to elude you, as if the animal in question were squirming or shaking itself loose of your grip, or turning to bite you and then take off, against all entreaties, into a mist of metaphor, where you must follow, closing the gate of this punctuation mark behind you; and on the other side everything is both less certain and suddenly, swimmingly, closer at hand: the sentence stops and looks around and starts comparing itself to the action of a drug, to the light-sucking lens of a camera or the slow apparition of an image (lets say a face) on photographic paper, to festive decorations enchained about a church, or a storm speeding across the lake towards the place where its writer is sitting, or, or, or the sentence, which considers itself very modern, has grown tired of such figural adventures, not to speak of the antiquarys accumulation of clauses and subclauses, so that you start to notice, start to notice certain acts of repetition (Repetition. But also. Interruption.) that give the sentence a faceted, crystalline quality it will always ever after possess, whether it wants to talk about sickness and health, about the sunlight outside Rome, a New York afternoon, a white boy who wants to be black, or the disappearing sun in daytime, even if it is short, even if it is long, even (especially) if it still aspires to its old elegance, the lofty periods, the plush vocabulary, on which subject, by the way, the sentence has been taking notesa sample from the archive: slumgullion, mandrelled, greaved, eidetic, soricine, macula, flimmering, glop, exorb, chthonic, brumous, moil, ort, flygolding, chlamysand keeping tabs, in case these riches come in useful, because who can say what the sentence will need or want in the future, what expansions or contractions it may endure or enjoy, what knowledge need to muster and deploy, whose speech to steal and celebrate, where to be heard the rhythms it needs to live, to live and let slip your overly attentive attention, interesting itself in things and bodies and abstractions that you no longer recognize and whose names and outlines you will have to entrust to the slippery sentence itself, which it turns out knows more than you do, knows when to seize on and worry the world and when to let go, as its doing now, and go skittering away from you (its maker not its keeper), beating the bounds of its invisible domain.

For about twenty-five years I have been copying sentences into the back pages of whatever notebook I happen to be using, using mostly for other purposes. The brand, style and quality of these notebooks has changed a few times, but not their dimensions, or not much: they are all more or less A5, paperback-sized, at home in the hand or on the desk. Of course there are sentences elsewhere in these books: even the briefest, most telegraphic, verbless note is a sentence of sorts. And then there are the quotations and paraphrases from books, descriptions of people and places and things, as well as rough drafts of sentences later to be properly written, or not written. But the end-of-notebook sentences are different, even if some of them come from books Im reviewing and so on. Unconnected to duty or deadlines, to projects per se, they compose a parallel timelineof what?

I suppose the word is: affinity. On the bookshelves behind me as Im writing now, there are forty-five of those notebooks, a phalanx of black spines interrupted by the occasional red or blue, and even one or two spiral bindings. One day, I might track down others, which are lost among books and papers, and put the whole lot in chronological order. For now, choose a notebook from the shelves at random, and who knows what sliver of time will come with it, or what sentences. Here are some examples from a notebook I was using late in 2009. Walter Benjamin: Our life, it can be said, is a muscle strong enough to contract the whole of historical time. Walter Pater: In aesthetic criticism the first step towards seeing ones object as it really is, is to know ones own impression as it really is. (This one, it turns out, is extracted from a longer sentence in The Renaissance.) Tim Robinson: Of course the justness of a word sometimes resides in the precise degree of discomfort it inflicts. Robinson again: All you can feel is the cold, flowing down from the pulseless heart of the icefield. D.H. Lawrence: And my diamond might be coal or soot, and my theme is carbon. Finally, a fragment from a sentence, unattributed: had fitted, as the air for human breath, so the clouds.... (It is by John Ruskin.) Apart from the dismaying maleness of this selection, and some progress away from the abstractions of history and aesthetics towards the particulars of geology and weather, I notice something else. The first three sentences seem the sort of thing I might have saved for subsequent quotation; they sound self-assured, prodding their general points home. Between the two sentences from Robinsonan incomparable essayist on earth and atmosphereeverything changes. What did I think I was seeing in these other sentences? Or hearing, or hoping to emulate? With the first three, its obvious: an epigrammatic snap, some truth at odds with received wisdom, a relevance to writing, a degree of portability: as a critic, I can imagine insinuating any one of them into an essay or review. Maybe not without a little pomp and satisfaction. But the others? How to say, because this must be the word, what I

New York Review Books New York

New York Review Books New York