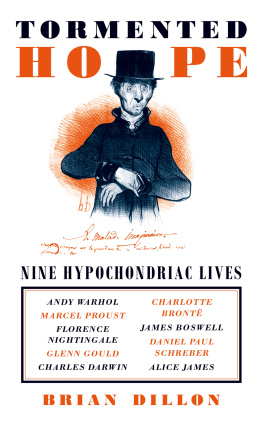

Tormented Hope

Nine Hypochondriac Lives

BRIAN DILLON

PENGUIN IRELAND

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephens Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd)

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL , England

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA

Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia

(a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd)

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4P 2Y3

(a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.)

Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi 110 017, India

Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, North Shore 0632, New Zealand

(a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd)

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL , England

www.penguin.com

First published 2009

Copyright Brian Dillon, 2009

The moral right of the author has been asserted

All rights reserved

Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book

ISBN: 978-0-14-195793-7

To Felicity Dunworth

My body is that part of the world which my thoughts are able to change.

Georg Christoph Lichtenberg, The Waste Books

Introduction: A History of Hypochondria

You were well one minute ago, and this minute you are unwell. Your symptoms came on, and with them your fear, in a stray moment of solitude. Perhaps you and your body were alone in the bathroom, with leisure to examine your naked flesh, time enough for your fingers to find a lump where no lump should be, for the unsteamed mirror to reveal a rash or for your hand to pause as you reached for the soap, an obscure twinge dragging at your innards. Or perhaps it happened at night, while you were alone, or as your lover slumbered: on the verge of sleep a sudden sensation as of something shifting inside, a slow waking in the dark as a dull ache intruded on your dreams, or towards dawn a more diffuse feeling that mortality was near. Maybe it was broad daylight, in the midst of the diurnal round a conversation half-overheard, concerning a colleagues recent diagnosis; a radio interview with the victim of a rare and debilitating disease; a newspaper article, skimmed during the dead time of your daily commute, in which you recognized your own poor diet and sedentary habits.

However the suspicion may have insinuated itself, in the days that follow it seems to sharpen in your mind. Your symptoms appear to point to a specific illness: it is the disease, perhaps, that you have feared all your life, or in recent years; the disease of which a parent died. Your first fears begin to condense into certainties, no less fearful. You feel compelled to research your disease. Unthinking, or thinking too far ahead, you type both your symptoms and the name of the illness of which you are afraid into a search engine, and inevitably there are hundreds of hits. You snatch what time you can to trawl through the relevant websites; if your lifestyle allows, many hours and even whole days can vanish like this. Everything starts to encircle your symptoms. At times, you succeed in distracting yourself: the pain subsides, the blemish or lump seems less massive than it did the day before. But your thoughts lack the lightness or velocity to escape the gravitational pull of your fear.

The alteration is as yet invisible to those around you, but your life has been changed for good. You begin secretly to date everything in relation to the moment you first realized that something was wrong. Your previous existence now looks idyllic and illusive, shadowed in retrospect by what was to come. But although everything has changed it is all, also, quite familiar. You have been here before, felt the same sickening plummet of discovery, the same slow creep of horror as the sinister truth slithered into view. And yet this time, you feel certain, is different. This time, the evidence is irrefutable.

Why then this strange pang of hope as at last, after days, weeks or perhaps months of solitary fretting, you find yourself in a physicians waiting room, rehearsing the story of your symptoms, preparing to expose your body to the uncompromising gaze and implacable verdict of the professional? In the consulting room, your face flushed and your heart racing the blood-pressure test will be skewed by your anxiety you watch the doctor heft your file onto the desk, or scroll through your notes on-screen, and you begin, like a penitent in the close precincts of the confessional, to recite your symptoms. The problem, let us say, is with your neck. Or perhaps because at this point the plot may ramify in countless directions, like a bacterium flourishing beneath a microscope it is your chest that troubles you, or your abdomen. There may be stiffness of the joints, aches in the muscles, unexplained tingling at the extremities. The guts are very likely to be affected: you might report bouts of indigestion, attacks of wind, discomfort on moving the bowels. It is possible that the skin has erupted, or begun to itch or sting even though no lesion or rash is visible. The heart seems to beat, you report, with alarming force or rapidity; the breath is shallow or painful. Your head hurts all the time, or only intermittently, in different places each time, or in the same place, insistently. Curiously, no matter the symptoms with which you present and you may or may not have noticed this fact yourself they seem clustered on the left side of your body. The pain, you admit in answer to the doctors question, is not severe, nor are you sure that it is getting any worse. But it concerns you, you say, understating now the terror that has brought you here, and you thought it was important to have it checked out.

Time the time spent being afraid and the time you imagine that you have left has seemed to contract to this brief interlude: the crucial encounter between doctor and patient. It seems to you now, however, as the physician pauses to consider what you have just described, and glances again at your notes before proceeding to the physical examination, that time has become elastic once more, and stretches around you in the consulting room, filled with uncertainty.

You might reflect, in the interval before the doctor speaks or lays hands on your trembling person, that you have neglected to mention your most striking symptom. It is this: in the days since you first suspected your body of its treachery, you have started to live at the edge of your own life, to withdraw into a state of mind at once alert and somnolent. You listen constantly, in a kind of trance, for communications from your body; it is as if you have become a medium, and your organs a company of fretful ghosts, whispering their messages from the other side. In your daily life, loved ones, friends and colleagues have started to notice that you are hardly there. Occasional, occulted signals come through to them to the effect that you are unwell, but the news, you have remarked, seems hardly to have registered in their minds. It is they who seem to you distracted, unperturbed by the mounting evidence of your ill health. You have long been accustomed to trying to control your body, to neutralize in advance its unpredictable, unruly nature. Now it seems that you have to take charge of other people too: to persuade them, friends and family alike, that there is something amiss. You can feel all certainty slipping away as the face of your doctor, like the face of the last friend or loved one you told of your fear, fails to set itself in an expression of unalloyed assurance. It has seemed to you lately that nobody has been taking you or your symptoms seriously; now it appears that nobody, not even your doctor (who knows you so well), will give you the straight answer you so anxiously need.