Contents

Guide

MIND & BODY

MIND & BODY

Mental Exercises for

Physical Wellbeing

Physical Exercises for

Mental Wellbeing

Published in 2021 by The School of Life

First published in the USA in 2021

70 Marchmont Street, London WC1N 1AB

Copyright The School of Life 2021

Design and illustrations by Marcia Mihotich

Typeset by Kerrypress

Printed in Latvia by Livonia

All rights reserved. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not be resold, lent, hired out or otherwise circulated without express prior consent of the publisher.

A proportion of this book has appeared online at

www.theschooloflife.com/thebookoflife

Every effort has been made to contact the copyright holders of the material reproduced in this book. If any have been inadvertently overlooked, the publisher will be pleased to make restitution at the earliest opportunity.

The School of Life is a resource for helping us understand ourselves, for improving our relationships, our careers and our social lives as well as for helping us find calm and get more out of our leisure hours. We do this through creating films, workshops, books, apps and gifts.

www.theschooloflife.com

ISBN 978-1-912891-82-5

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

CONTENTS

Introduction: The mind-body problem

One of the most peculiar things about being human is that we exist as both minds and bodies. We are in part miraculous machines hung off collagen and calcium skeletons, irrigated by five litres of watery plasma richly packed with erythrocytes and leukocytes driven along 100,000 miles of blood vessels by a pump that beats 100,000 times a day using power released by the breakdown of potato chips and carrot sticks, buttered toast and lemon pie, all tightly sealed in a one-litre vat filled with a mixture of hydrochloric acid and potassium and sodium chloride.

And yet we are at the same time minds that have memories, imagination, emotions and ideals, unique centres of consciousness that can blend an infinity of fears and insights, excitements and regrets into an unfolding story of identity; minds that can conjure up worlds from spectral blankness, that can classify and order chaos, that can turn mute cries into poetry and agony into arias, that can devise ideas to die or live for and that crave beauty and aspire to wisdom all within a squelchy 1,400-gram walnut encased in a cavity discreetly silent as to the many universes it contains.

A brain tells us nothing of what it is like to have a mind.

But the two sides of our nature are not only very different; they are also engaged in ongoing and often painful conflict. We wish to be loved and respected for the subtleties of our minds but are in practice more likely to be judged on the shape of our nose and the suppleness of our skin; we seek to impress and reassure with a suggestion of dignity but cant put ourselves beyond the risk of burping or of breaking wind; we long for calm and reason but are fatefully betrayed by debauchery and licentiousness. We hope to honour those we love, do justice to our talents and finish writing our books, but may be ineluctably drawn to nightclubs, too many drinks and the more shameful corners of the internet.

And what is worse, without our conscious selves having any say in the matter, our bodies have catastrophic inclinations to fall apart and die long before we have got the hang of living; before we have tired of seeing springtime or done a fraction of what we suspect we might be capable of.

Gerard van Honthorst, The Steadfast Philosopher, 1623. Mind and body are set in opposed and often inimical directions.

This cluster of tensions, pains and incompatibilities might collectively be referred to as the mind-body problem. Those of a philosophical bent will know that, in academic circles, the mind-body problem means something quite specific. It has been the term used to describe a very particular question identified in the 1640s by the French mathematician and philosopher Ren Descartes (15961650). Descartes wished to know how a purely mental thought could have physical consequences: how, for instance, might a wish to drink a glass of water lead one physically to take a sip? Descartes imagined the material world like a complex set of billiard balls: everything happens in it because one thing pushes another. But a thought doesnt seem to have any material properties: it has no physical weight, so how could it be involved in pushing anything? How could it make something physical move? How could a weightless thought cause the muscles of our fingers to contract? Although no really convincing strategy for answering this question was available until the rise of neuroscience at the end of the 20th century, the question of how thoughts might lead to physical motion seriously troubled only a very small minority. It would therefore be a pity if the resonant phrase the mind-body problem were forever to be attached only to this arcane conundrum, the answer to which no element of human happiness has ever seriously depended upon. It therefore feels fitting to reappropriate and employ the phrase to refer to all the dilemmas thrown up for us by our dual nature as physical bodies on the one hand and as thinking and dreaming souls on the other.

At the core of the mind-body problem thus redefined is the question of whether there might be a way of reducing the strife between the different parts of ourselves. What is the best way to flourish given our dual natures? Can mind and body be constructive companions rather than ill-tempered enemies? Can we learn to accommodate our varied selves with grace? This is the enquiry at the heart of this book, a journey to discover ways of reconciling mind and body in the name of leading more harmonious and less fractured lives.

Over the centuries, there have been some unfortunate ways of responding to the tensions between mind and body. The most notable and emblematic of these began in the early 3rd century with the Christian intellectual and saint Origen of Alexandria.

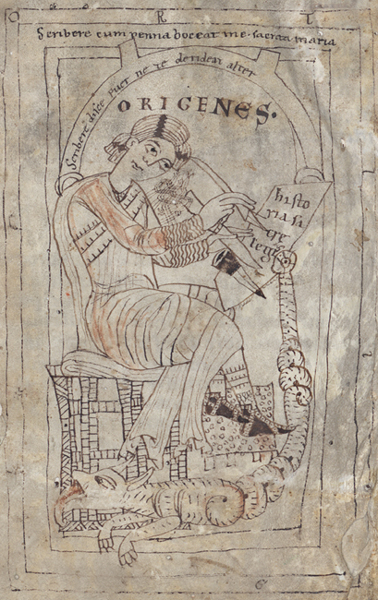

Unknown artist, Origen, from Numeros homilia XXVII, c. 1160.

Origen of Alexandria: the dawn of the mind-body problem.

Origen was an extremely pious man, one of whose earliest wishes was to die as a martyr to Christ. He thought of revealing his faith to the Roman authorities and then awaiting the mandatory death sentence, but after mentioning his ambition to his mother, let himself be persuaded to become an academic instead. He turned out to have great talent in this area, and wrote twenty-five volumes of commentary on the Gospel of St Matthew and 2,000 treatises on biblical hermeneutics.

But despite his devotion to his holy studies, Origen couldnt ignore certain powerful physical attractions that coursed through him. He came to see the body as a prison and argued that we are fallen angels who used to live in heaven but were turned away from God and, as a punishment, had our souls locked up in packets of sinful, suffering flesh. After growing overwhelmed by feelings for one of his biblical students, reputedly the most beautiful nun in Egypt, Origen decided to cut off his penis and testicles in order to avoid further temptation and make himself a eunuch for the kingdom of heaven. Whether he actually did so is a matter of historical dispute, but Origens supporters (and the Christian Church more broadly) enthusiastically spread the rumour as proof of exemplary virtue and wisdom, rather than as others might have proposed an indication of psychopathology.