Copyright Acknowledgments

Grateful acknowledgment is made to the following publishers for permission to reproduce extracts from previously published material:

Cambridge University Press: Human All Too Human, Friedrich Nietzsche, trans. R. J. Hollingdale, 1996; and On the Genealogy of Morality, Friedrich Nietzsche, trans. Carol Diethe, 1996; Dover Publications: World as Will and Representation, Arthur Schopenhauer, trans. Duncan Large, 1988; Oxford University Press: extracts reprinted from Twilight of the Idols, Friedrich Nietzsche, trans. Duncan Large (Oxford Worlds Classics, 1998), by permission of Oxford University Press; extracts reprinted from Parerga and Paralipomena, Arthur Schopenhauer, (volumes I and II, trans. E. F. Payne, 1974) by permission of Oxford University Press; Penguin Books: Early Socratic Dialogues, Plato, trans. Iain Lane, 1987; The Last Days of Socrates, Plato, trans. Hugh Tredennick, 1987; Protagoras and Meno, Plato, trans. W. K. C. Guthrie, 1987; Dialogues and Letters, Seneca, trans. C. D. N. Costa, 1997; Letters from a Stoic, Seneca, trans. Robin Campbell, 1969; The Complete Essays, Michel de Montaigne, trans. M. A. Screech, 1991; Beyond Good and Evil, Friedrich Nietzsche, trans. R. J. Hollingdale, 1996; and Ecce Homo, Friedrich Nietzsche, trans. R. J. Hollingdale, 1979; Random House, Inc.: extracts from The Will to Power by Friedrich Nietzsche, trans. Walter Kaufmann and R. J. Hollingdale. Copyright 1967 by Walter Kaufmann. Extracts from The Gay Science by Friedrich Nietzsche, trans. Walter Kaufmann. Copyright 1974 by Random House, Inc. Reprinted by permission of Random House, Inc.

Picture Acknowledgments

The photographs in the book are used by permission and courtesy of the following:

Aarhus Kunstmuseum:

Acknowledgments

I am much indebted to the following authorities for their comments on chapters of this book: Dr Robin Waterfield (for Socrates), Professor David Sedley (for Epicurus), Professor Martin Ferguson Smith (for Epicurus), Professor C. D. N. Costa (for Seneca), the Reverend Professor Michael Screech (for Montaigne), Reg Hollingdale (for Schopenhauer) and Dr Duncan Large (for Nietzsche). I am also greatly indebted to the following for their comments: John Armstrong, Harriet Braun, Michele Hutchison, Noga Arikha and Miriam Gross. I would like to thank: Simon Prosser, Lesley Shaw, Helen Fraser, Michael Lynton, Juliet Annan, Grinne Kelly, Anna Kobryn, Caroline Dawnay, Annabel Hardman, Miriam Berkeley, Chloe Chancellor, Lisabel McDonald, Kim Witherspoon and Dan Frank.

ALSO BY ALAIN DE BOTTON

On Love

The Romantic Movement

Kiss & Tell

How Proust Can Change Your Life

The Art of Travel

ALAIN DE BOTTON

The Consolations of PhilosophyAlain de Botton is the author of On Love, The Romantic Movement, Kiss and Tell, How Proust Can Change Your Life, The Consolations of Philosophy, and The Art of Travel. His work has been translated into twenty languages. He lives in Washington, D.C., and London, where he is an Associate Research Fellow of the Philosophy Programme of the University of London, School of Advanced Study.

The dedicated Web site for Alain de Botton and his work is www.alaindebotton.com.

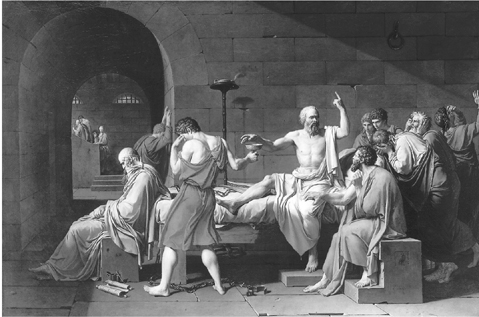

A few years ago, during a bitter New York winter, with an afternoon to spare before catching a flight to London, I found myself in a deserted gallery on the upper level of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. It was brightly lit, and aside from the soothing hum of an under-floor heating system, entirely silent. Having reached a surfeit of paintings in the Impressionist galleries, I was looking for a sign for the cafeteria where I hoped to buy a glass of a certain variety of American chocolate milk of which I was at that time extremely fond when my eye was caught by a canvas which a caption explained had been painted in Paris in the autumn of 1786 by the thirty-eight-year-old Jacques-Louis David.

()

Socrates, condemned to death by the people of Athens, prepares to drink a cup of hemlock, surrounded by woebegone friends. In the spring of 399 BC , three Athenian citizens had brought legal proceedings against the philosopher. They had accused him of failing to worship the citys gods, of introducing religious novelties and of corrupting the young men of Athens and such was the severity of their charges, they had called for the death penalty.

()

Socrates had responded with legendary equanimity. Though afforded an opportunity to renounce his philosophy in court, he had sided with what he believed to be true rather than what he knew would be popular. In Platos account he had defiantly told the jury:

So long as I draw breath and have my faculties, I shall never stop practising philosophy and exhorting you and elucidating the truth for everyone that I meet And so gentlemen whether you acquit me or not, you know that I am not going to alter my conduct, not even if I have to die a hundred deaths.

And so he had been led to meet his end in an Athenian jail, his death marking a defining moment in the history of philosophy.

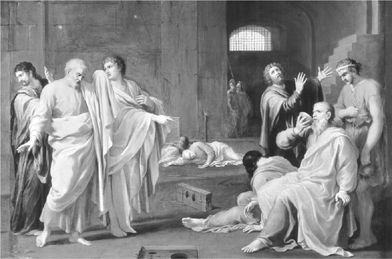

An indication of its significance may be the frequency with which it has been painted. In 1650 the French painter Charles-Alphonse Dufresnoy produced a Death of Socrates, now hanging in the Galleria Palatina in Florence (which has no cafeteria).

()

The eighteenth century witnessed the zenith of interest in Socrates death, particularly after Diderot drew attention to its painterly potential in a passage in his Treatise on Dramatic Poetry.

tienne de Lavalle-Poussin, c. 1760 ()

Jacques Philippe Joseph de Saint-Quentin, 1762

Pierre Peyron, 1790 ()

Jacques-Louis David received his commission in the spring of 1786 from Charles-Michel Trudaine de la Sablire, a wealthy member of the Parlement and a gifted Greek scholar. The terms were generous, 6,000 livres upfront, with a further 3,000 on delivery (Louis XVI had paid only 6,000 livres for the larger Oath of the Horatii). When the picture was exhibited at the Salon of 1787, it was at once judged the finest of the Socratic ends. Sir Joshua Reynolds thought it the most exquisite and admirable effort of art which has appeared since the