Alain de Botton

Alain de Botton is the author of essays on themes ranging from love and travel to architecture and philosophy. His bestselling books include How Proust Can Change Your Life, The Art of Travel, and The Architecture of Happiness. He lives in London, where he is the founder and chairman of The School of Life (www.theschooloflife.com) and the creative director of Living Architecture (www.living-architecture.co.uk).

B OOKS BY A LAIN DE B OTTON

On Love

How Proust Can Change Your Life

The Consolations of Philosophy

The Art of Travel

Status Anxiety

The Architecture of Happiness

A Week at the Airport

The Pleasures and Sorrows of Work

Religion for Athiests

Art as Therapy (with John Armstrong)

How to Think More About Sex

The News: A Users Manual

The Course of Love

How to Take Your Time

from How Proust Can Change Your Life

Alain de Botton

A Vintage Short

Vintage Books

A Division of Penguin Random House LLC

New York

Copyright 1997 by Alain de Botton

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Vintage Books, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York, and in Canada by Random House of Canada, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited, Toronto. Originally published in hardcover as part of How Proust Can Change Your Life in the United States by Pantheon Books, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York, in 1997.

Vintage and colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

The Cataloging-in-Publication Data for How Proust Can Change Your Life is available from the Library of Congress.

Vintage eShort ISBN9780525435020

Cover design by Perry De La Vega

www.vintagebooks.com

v4.1

a

Contents

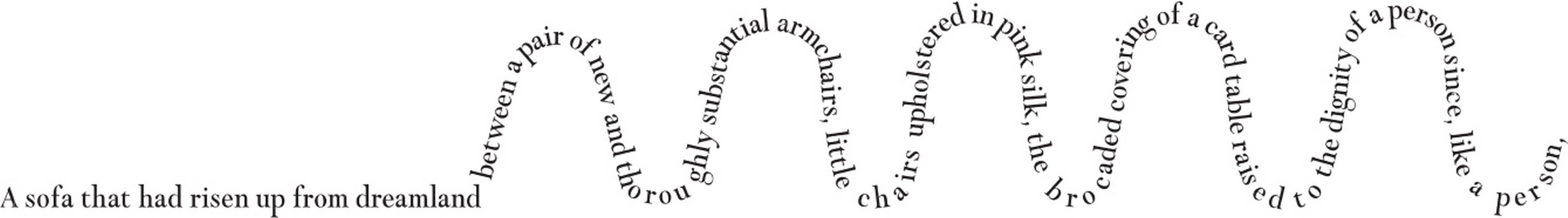

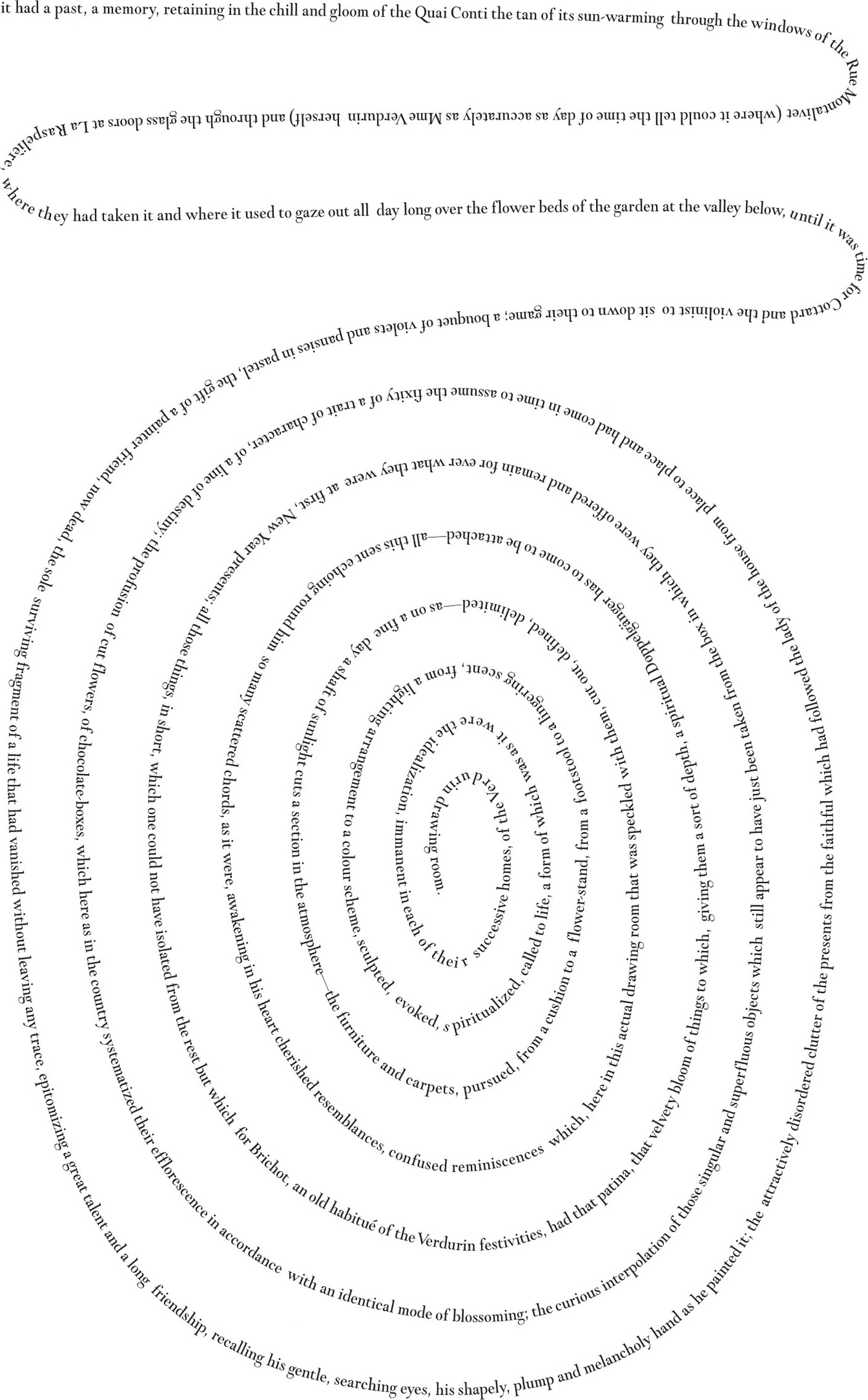

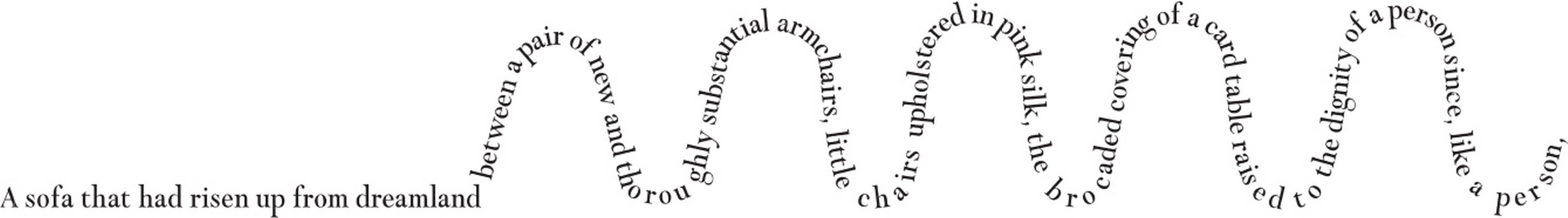

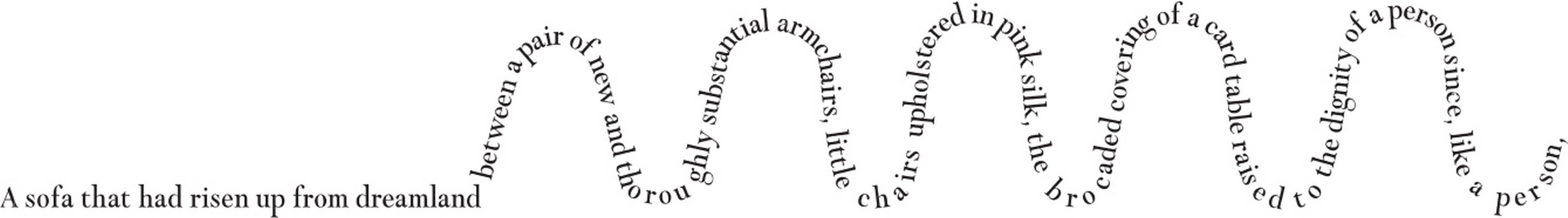

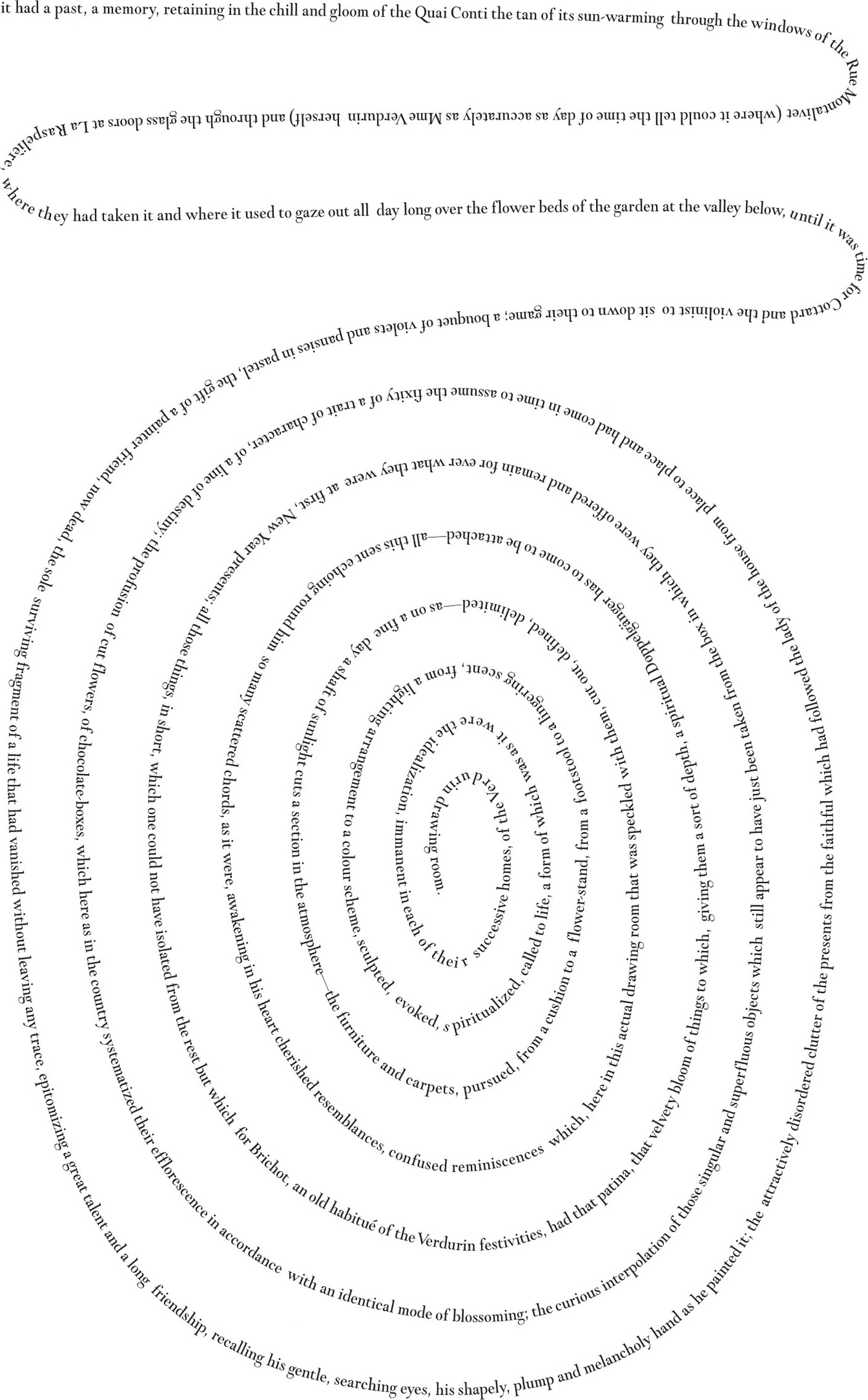

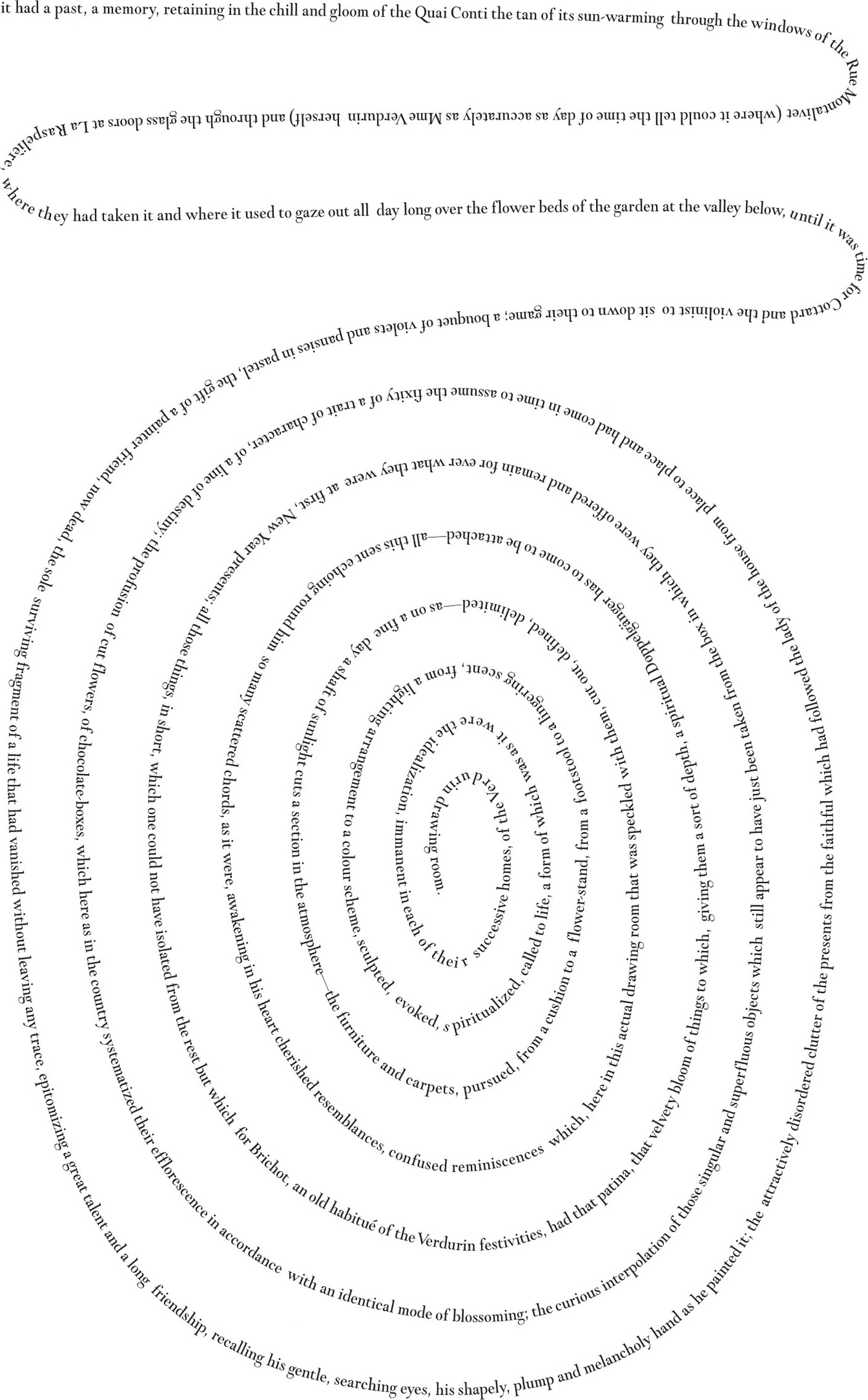

Whatever the merits of Prousts work, even a fervent admirer would be hard pressed to deny one of its awkward features: length. As Prousts brother, Robert, put it, The sad thing is that people have to be very ill or have broken a leg in order to have the opportunity to read In Search of Lost Time. And as they lie in bed with their limb newly encased in plaster or a tubercle bacillus diagnosed in their lungs, they face another challenge in the length of individual Proustian sentences, snakelike constructions, the very longest of which, located in the fifth volume, would, if arranged along a single line in standardized text, run on for a little short of four meters and stretch around the base of a bottle of wine seventeen times:

Alfred Humblot had never seen anything like it. As head of the esteemed publishing house Ollendorf, he had, early in 1913, been asked to consider Prousts manuscript for publication by one of his authors, Louis de Robert, who had undertaken to help Proust get into print. My dear friend, I may be dense, replied Humblot after taking a brief and clearly bewildering glance at the opening of the novel, but I fail to see why a chap needs thirty pages to describe how he tosses and turns in bed before falling asleep.

He wasnt alone. Jacques Madeleine, a reader for the publishing house Fasquelle, had been asked to look at the same bundle of papers a few months earlier. At the end of seven hundred and twelve pages of this manuscript, he had reported, after innumerable griefs at being drowned in unfathomable developments and irritating impatience at never being able to rise to the surfaceone doesnt have a single, but not a single clue of what this is about. What is the point of all this? What does it all mean? Where is it all leading? Impossible to know anything about it! Impossible to say anything about it!

Madeleine nevertheless had a go at summarizing the events of the first seventeen pages: A man has insomnia. He turns over in bed, he recaptures his impressions and hallucinations of half-sleep, some of which have to do with the difficulty of getting to sleep when he was a boy in his room in the country house of his parents in Combray. Seventeen pages! Where one sentence (at the end of page 4 and page 5) goes on for forty-four lines.

Since all other publishers sympathized with these sentiments, Proust was forced to pay for the publication of his work himself (and was left to enjoy the regrets and contrite apologies that flowed in a few years later). But the accusation of verbosity was not so fleeting. At the end of 1921, his work now widely acclaimed, Proust received a letter from an American, who described herself as twenty-seven, resident in Rome, and extremely beautiful. She also explained that for the previous three years she had done nothing with her time other than read Prousts book. However, there was a problem. I dont understand a thing, but absolutely nothing. Dear Marcel Proust, stop being a poseur and come down to earth. Just tell me in two lines what you really wanted to say.

The frustration of the Roman beauty suggests that the poseur had violated a fundamental law of length stipulating the appropriate number of words in which an experience could be related. He had not written too much per se; he had digressed intolerably given the significance of the events under consideration. Falling asleep? Two words should cover it, four lines if the hero had indigestion or if a Labrador was giving birth in the courtyard below. But the poseur hadnt digressed simply about sleep; he had made the same error with dinner parties, seductions, jealousies.

It explains the inspiration behind the All-England Summarise Proust Competition, once hosted by Monty Python in a south coast seaside resort, a competition that required contestants to prcis the seven volumes of Prousts work in fifteen seconds or less, and to deliver the results first in a swimsuit and then in evening dress. The first contestant was Harry Baggot from Luton, who hurriedly offered the following:

Prousts novel ostensibly tells of the irrevocability of time lost, of innocence and experience, the reinstatement of extra-temporal values and time regained. Ultimately the novel is both optimistic and set within the context of human religious experience. In the first volume, Swann visits

But fifteen seconds did not allow for more. A good attempt, declared the game-show host with dubious sincerity, but unfortunately he chose a general appraisal of the work before getting on to specific details. The contestant was thanked for his attempt, commended on his swimming trunks, and shown off stage.

Despite this personal defeat, the contest as a whole remained optimistic that an acceptable summary of Prousts work was possible, a faith that what had originally taken seven volumes to express could reasonably be condensed into fifteen seconds or less, without too great a loss of integrity or meaning, if only an appropriate candidate could be found.