Contents

Guide

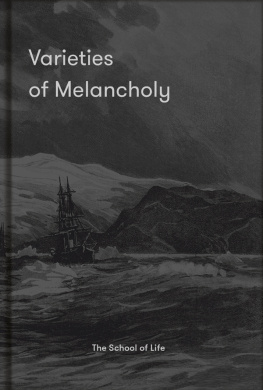

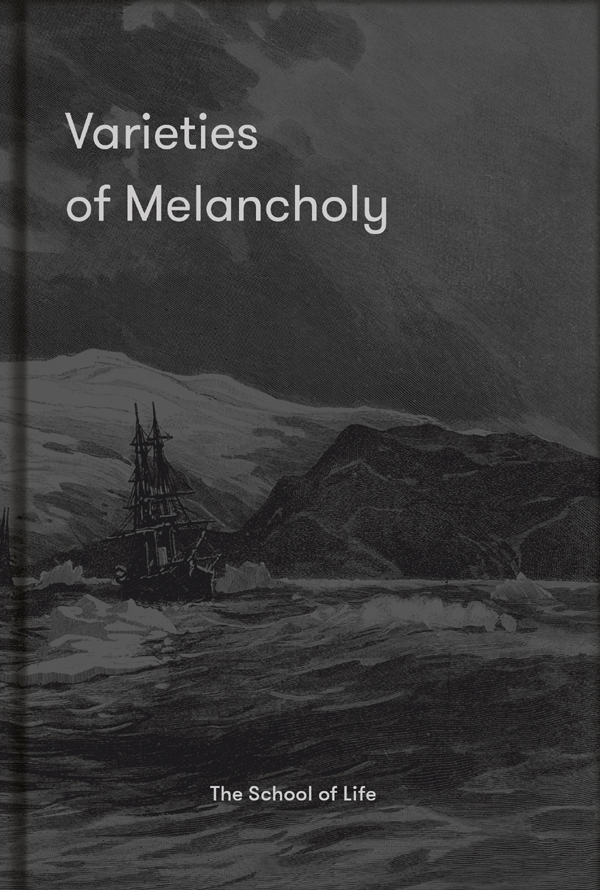

Varieties

of Melancholy

Published in 2021 by The School of Life

First published in the USA in 2021

70 Marchmont Street, London WC1N 1AB

Copyright The School of Life 2021

Cover design by Marcia Mihotich

Typeset by Kerrypress

Printed in Latvia by Livonia

All rights reserved. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not be resold, lent, hired out or otherwise circulated without express prior consent of the publisher.

A proportion of this book has appeared online at

www.theschooloflife.com/thebookoflife

Every effort has been made to contact the copyright holders of the material reproduced in this book. If any have been inadvertently overlooked, the publisher will be pleased to make restitution at the earliest opportunity.

The School of Life is a resource for helping us understand ourselves, for improving our relationships, our careers and our social lives as well as for helping us find calm and get more out of our leisure hours. We do this through creating films, workshops, books, apps and gifts.

www.theschooloflife.com

ISBN 978-1-912891-94-8

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Contents

Introduction

There are a great many ways of handling the unhappiness that inevitably comes with being human: we may rage or despair, we may scream or lament, we may sulk or cry. But there is perhaps no better way to confront the misery and incompleteness with which we are cursed than to settle on an emotion still too seldom discussed in the frenetic modern world: melancholy. Given the scale of the challenges we are up against, our goal shouldnt be to try to always be happy, but also as importantly to master ways of settling wisely and fruitfully into gentle sorrow. If we can refer to better and worse ways of suffering, then melancholy deserves to be celebrated as the optimal means of encountering the challenges of being alive.

It is key to determine from the outset what melancholy is not. It isnt bitterness. The melancholy person lacks any of the bitter ones latent optimism and, therefore, has no need to respond to disappointments with a resentful snarl. From an early age, they understood that most of life would be about pain, and structured their worldview accordingly. They arent, of course, delighted by the suffering, the meanness and the hardship, but nor can they muster the confidence to believe that it was really meant to be any other way.

At the same time, melancholy is not anger. There was perhaps crossness somewhere at the outset, but it has long since dissipated into something far more mellow, more philosophical and more indulgent to the imperfection of everything. The melancholy greet what is terrible and frustrating with a weary of course: of course the partner wants to break up (just as we had finally grown used to them); of course the business is now closing; of course friends are deceptive; and of course the doctor is advising a referral to a specialist. These are exactly the sorts of horrific things that life has in store.

Nevertheless, the melancholy manage to resist paranoia. Bad things certainly happen, but not just specifically to them, and not for anything exceptional that they have done wrong: they are simply what befalls averagely flawed humans who have been around for a while. Everyones luck runs out soon enough. The melancholy have factored in problems long ago.

Nor are the melancholic, for that matter, cynical: they arent using their pessimism in a defensive way. They arent compelled to denigrate everything in case they get hurt. Theyre still able to take pleasure in small things and to hope that one or two details might every now and then go right. They just know that nothing has been guaranteed.

Because melancholy is based on an awareness of the imperfection of everything, on the perennial gap between what should ideally be and what actually is, the melancholic are especially receptive to small islands of beauty and goodness. They can be deeply moved by flowers, by a tender moment in a childrens book, by an unexpected gesture of kindness from someone they barely know, by sunlight falling on an old wall at dusk.

Where the melancholy suffer particularly is around demands to be cheerful. Office culture may be hard, and consumer society grating. Certain countries and cities seem more indulgent to the feeling than others. Melancholy is naturally at home in Hanoi and Bremen; it almost impossible to maintain in Los Angeles.

The aim of this book is to rehabilitate melancholy, to give it a more prominent and defined role and to make it easier to discuss. A community may be described as civilised to the extent to which it is prepared to countenance a prominent role for the emotion to accept the idea of a melancholy love affair or a melancholy child, a melancholy holiday or a melancholy company culture. Certain ages the 1400s in Italy, Edo-period Japan, late-19th-century Germany have been more generously inclined to melancholy than others, granting the feeling prestige in a way that helped individuals to feel less persecuted or strange when it came to visit. The goal should be the creation of a more melancholically literate and accepting contemporary world.

What follows is a portrait of different kinds of melancholy. The reader is invited to think through their own examples, a task in which we are all potential experts. With melancholy returned to its rightful place, we will learn that the most sincere way to get to know someone is simply and directly to ask, with kindness and fellow-feeling: and what makes you melancholy?

Nicholas Hilliard, Young Man Among

Roses, c. 15851595

Isaac Oliver, Edward Herbert, 1st

Baron Herbert of Cherbury, 16131614

Intelligence & Melancholy

Early on in the history of melancholy, the Greek philosopher Aristotle was said to have raised a question which cant help but sound a bit smug: Why is it that so many of those who have become outstanding in philosophy, statesmanship, poetry or the arts have been melancholic? As evidence of a link between melancholy and brilliance, Aristotle cited Plato, Socrates, Hercules and Ajax. The association stuck: in the Medieval period, melancholic people were said to have been born under the sign of Saturn, the then furthest known planet from the Earth, associated with cold and gloom but also with the power to inspire extraordinary feats of imagination. There developed pride in being melancholic; such people could perhaps discern things that the more cheerful would miss.

Proud of their identities as ambassadors of sadness, young English aristocrats commissioned portraits of themselves in melancholy poses, wearing melancholys characteristic colour (black) and gazing forlornly into the middle distance, sighing at an imperfection that they were smart enough not to deny.

In 1514, Albrecht Drer depicted the figure of Melancholy as a dejected angel, surrounded by a range of neglected scientific and mathematical instruments. To one side of the angel he placed a polyhedron, one of the most complicated but technically perfect of geometric forms. The angel had fallen into dejection the suggestion ran at the contrast between her longing for rationality, precision, beauty and order, and the actual conditions of the world.