EARLY MODERN POETICS IN MELVILLE AND POE

For my father, Marvin R. Engel, whose stories about vast swimming lizards of the Galapagos fired my imagination early on; and my grandparents, Minnie and Ned Salomon, whose oversized edition of Dores Raven brought me to literature sooner rather than later.

Early Modern Poetics in Melville and Poe

Memory, Melancholy, and the Emblematic Tradition

WILLIAM E. ENGEL

The University of the South, USA

ASHGATE

William E. Engel 2012

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publisher.

William E. Engel has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as the author of this work.

Published by

Ashgate Publishing Limited

Wey Court East

Union Road

Farnham

Surrey, GU9 7PT

England

Ashgate Publishing Company

Suite 420

101 Cherry Street

Burlington

VT 05401-4405

USA

www.ashgate.com

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Engel, William E., 1957

Early modern poetics in Melville and Poe : memory, melancholy, and the emblematic tradition. 1. Melville, Herman, 18191891 Criticism and interpretation. 2. Poe, Edgar Allan, 1809 1849 Criticism and interpretation. 3. Influence (Literary, artistic, etc.) History 19th century.

I. Title

813.309-dc23

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Engel, William E., 1957

Early modern poetics in Melville and Poe : memory, melancholy, and the emblematic tradition / by William E. Engel.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-4094-3586-0 (hardcover : alk. paper) ISBN 978-1-4094-3587-7 (ebook)

1. Melville, Herman, 18191891. Encantadas. 2. Poe, Edgar Allan, 18091849. Raven. 3. Melville, Herman, 18191891Literary style. 4. Poe, Edgar Allan, 18091849Literary style. 5. Melville, Herman, 18191891KnowledgeLiterature. 6. Poe, Edgar Allan, 18091849KnowledgeLiterature. 7. Memory in literature. 8. Chiasmus. 9. Melancholy in literature. 10. Influence (Literary, artistic, etc.) I. Title. II. Title: Memory, melancholy, and the emblematic tradition.

PS2384.E63E54 2012

813.309dc23

2011040915

ISBN 9781409435860 (hbk)

ISBN 9781409435877 (ebk)

ISBN 9781409479208 (ebk-ePUB)

Contents

List of Figures

List of Tables

Acknowledgments

Many people have offered helpful suggestions on this project over the years, most notably Susan Bernstein, Tom Conley, Arthur Kinney, Inge Leimberg, Max Nnny, Scott Newstok, Carolyn Porter, and Brian Yothers. More recently, professional courtesy has been extended to me by Mark Bauerlein, Bainard Cowan, Jonathan Elmer, Samuel Otter, Scott Peeples, and Eric J. Sundquist. It is with fond memories of friendships made and renewed that I record my debt to the curators and members of the staff at the Newberry Library in Chicago; the Houghton Library at Harvard, which houses the Melville Collection; the Lilly Library at the University of Indiana, Bloomington; the Edgar Allan Poe Museum in Richmond; and the Baltimore Edgar Allan Poe Society, especially Jeffrey A. Savoye, whose indefatigable efforts have made available reliable electronic versions of Poes works. Iain Abernathy, formerly of the University of Liverpool, assisted me with online access to critical sources when I was off the grid.

Closer to home, George Core offered valuable advice regarding the organization of this project; Brown Patterson read much of the manuscript with care; and Tim Garner increased the clarity of the images a hundredfold. Others at Sewanee to whom I am indebted for timely and collegial conversations include Tam Carlson, John Gatta, John Grammer, Don Huber, Kelly Malone, and John Reishman. Special thanks go to Pamela Royston Macfie for so many things, but especially for allowing me to stray outside my area of primary specialization to teach nineteenth-century American fiction. I also acknowledge my gratitude to the University of the South for granting me a years sabbatical research leave during which time I came into contact with Ann Donahue at Ashgate, an exemplary editor. Also at Ashgate, Seth F. Hibbert (with the patience of Job) worked steadily with me to lick this book into shape. And I salute Angelo MacGuffin for his skills as a proofreader; anything I missed, he caughtand vice versa.

Portions of this book have been presented at academic conferences, chiefly the American Literature Association in San Francisco 2010, the International Poe Society in Philadelphia 2009 and Baltimore 2002, the Symposium on Iconicity in Krakow 2005, and the International Association for Philosophy and Literature in Helsinki 2005. A preliminary version of my treatment of The Encantadas appeared as Patterns of Recollections in Montaigne and Melville in Connotations 7.3 (19971998): 33254; and a streamlined version of my argument about The Raven is on track to appear in Deciphering Poe, Alexandra Urakova (ed.), currently under consideration at Lehigh University Press; I am grateful to the publishers for permission to reuse material from these essays.

Introduction

Stylistic Choices and Intellectual Armature

For the seed conveyeth with it not only the extract and single Idea of every part, whereby it transmits their perfections and infirmities; but double and over again; whereby sometimes it multipliciously delineates the same and to speak more strictly, parts of the seed do seem to contain the Idea and power of the whole.

Thomas Browne, Pseudodoxia Epidemica, VII.2 (1658)

This book is about pattern recognition and how the classical Art of Memory, by way of seventeenth-century aesthetic principles, gained a foothold in the writings of Herman Melville and Edgar Allan Poe. It traces a series of self-reflective organizational schemes associated with baroque artifice that Melville and Poe used to varying degrees in their work. Their knowledge of and recourse to the tropes, image clusters, and themes associated with the mnemonic habits of thought fundamental to the early modern emblem tradition enabled them to explore and express the extent of their literary inventions.

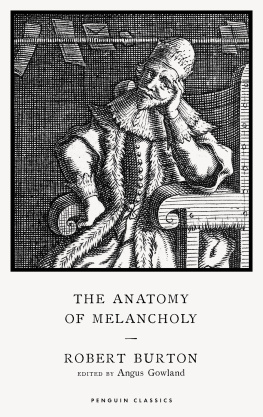

While other American writers of the period likewise were drawn to the cultural achievements of the seventeenth century, and although both Melville and Poe obviously had other literary models and intellectual debts, still there is something distinctive about how they pursued and incorporated the seemingly disjointed and meandering method of exposition characteristic of authors such as Robert Burton, Thomas Browne, and Francis Quarles. This does not mean that there was something peculiar to the time in which they wrote or in their personalities that led them to pursue this course in earnest. Rather, my inquiry into their pronounced affinity for writers and artists of this period, usually referred to as the baroque, follows from the episodic logic of Montaignes subtle understanding of the maxim by diverse means we arrive at the same end.

It is not unusual among literary critics of the period, such as Perry Miller, to see Melville and Poe as two maverick artists struggling against the party line of rival literary cliques, which made it difficult for either of them to win acceptance for their innovations. My goal is not to assert some grand paradigm-bending theory but instead, through a series of linked inquiries into their magazine publications, to point out and explain how Melville and Poe self-consciously turned to and reconfigured what they understood were admittedly exhausted themes, modes of expression, and formal schemes. They did so in a concerted effort to give voice to their nuanced understandings of mourning, melancholy, and loss. At the same time, their use of peculiarly baroque turns of thought and literary gestures enabled them to imbue their texts with a sense of companionable good cheer and broad if sly humor in the face of mortality.

Next page