PENGUIN BOOKS

STATUS ANXIETY

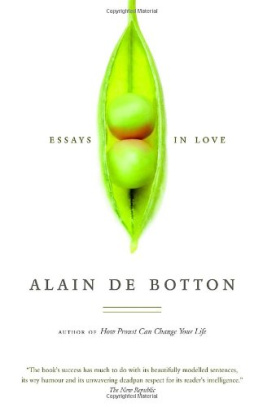

Alain de Botton was born in 1969. He is the author of Essays in Love (1993), The Romantic Movement (1994), Kiss and Tell (1995), How Proust Can Change Your Life (1997), The Consolations of Philosophy (2000), The Art of Travel (2002) and Status Anxiety (2004).

www.alaindebotton.com

STATUS ANXIETY

Alain de Botton

PENGUIN BOOKS

PENGUIN BOOKS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL , England

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA

Penguin Books Australia Ltd, 250 Camberweil Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia

Penguin Books Canada Ltd, 10 Alcorn Avenue, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4V 3B2

Penguin Books India (P) Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi 110 017, India

Penguin Group (NZ), cnr Airborne and Rosedale Roads, Albany, Auckland 1310, New Zealand

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL , England

www.penguin.com

First published by Hamish Hamilton 2004

Published in Penguin Books 2005

Copyright Alain de Botton, 2004

All rights reserved

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Designed by Austin Taylor

Except in the United States of America, this book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publishers prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser

ISBN: 978-0-14-193024-4

CONTENTS

DEFINITIONS

Status

Ones position in society; the word derived from the Latin statum or standing (past participle of the verb stare, to stand).

In a narrow sense, the word refers to ones legal or professional standing within a group (married, a lieutenant, etc.). But in the broader and here more relevant sense, to ones value and importance in the eyes of the world.

Different societies have awarded status to different groups: hunters, fighters, ancient families, priests, knights, fecund women. Increasingly, since 1776, status in the West (the vague but comprehensible territory under discussion) has been awarded in relation to financial achievement.

The consequences of high status are pleasant. They include resources, freedom, space, comfort, time and, as importantly perhaps, a sense of being cared for and thought valuable conveyed through invitations, flattery, laughter (even when the joke lacks bite), deference and attention.

High status is thought by many (but freely admitted by few) to be one of the finest of earthly goods.

Status Anxiety

A worry, so pernicious as to be capable of ruining extended stretches of our lives, that we are in danger of failing to conform to the ideals of success laid down by our society and that we may as a result be stripped of dignity and respect; a worry that we are currently occupying too modest a rung or are about to fall to a lower one.

The anxiety is provoked by, among other elements, recession, redundancy, promotions, retirement, conversations with colleagues in the same industry, newspaper profiles of the prominent and the greater success of friends. Like confessing to envy (to which the emotion is related), it can be socially imprudent to reveal the extent of any anxiety and, therefore, evidence of the inner drama is uncommon, limited usually to a preoccupied gaze, a brittle smile or an over-extended pause after news of anothers achievement.

If our position on the ladder is a matter of such concern, it is because our self-conception is so dependent upon what others make of us. Rare individuals aside (Socrates, Jesus), we rely on signs of respect from the world to feel tolerable to ourselves.

More regrettably still, status is hard to achieve and even harder to maintain over a lifetime. Except in societies where it is fixed at birth and our veins flow with noble blood, a high position hangs on what we can achieve; and we may fail due to stupidity or an absence of self-knowledge, macro-economics or malevolence.

And from failure will flow humiliation: a corroding awareness that we have been unable to convince the world of our value and are henceforth condemned to consider the successful with bitterness and ourselves with shame.

Thesis

That status anxiety possesses an exceptional capacity to inspire sorrow.

That the hunger for status, like all appetites, can have its uses: spurring us to do justice to our talents, encouraging excellence, restraining us from harmful eccentricities and cementing members of a society around a common value system. But, like all appetites, its excesses can also kill.

That the most profitable way of addressing the condition may be to attempt to understand and to speak of it.

PART ONE

CAUSES

I. LOVELESSNESS

The Desire for Status

There are common assumptions about which motives drive us to seek high status; among them, a longing for money, fame and influence.

Alternatively, it might be more accurate to sum up what we are searching for with a word seldom used in political theory: love. Once food and shelter have been secured, the predominant impulse behind our desire to succeed in the social hierarchy may lie not so much with the goods we can accrue or the power we can wield, as with the amount of love we stand to receive as a consequence of high status. Money, fame and influence may be valued more as tokens of and as a means to love rather than as ends in themselves.

How might a word, generally used only in relation to what we would want from a parent or a romantic partner, be applied to something we might want from and be offered by the world? Perhaps we could define love, at once in its familial, sexual and worldly forms, as a kind of respect, a sensitivity by one person to anothers existence. To be shown love is to feel ourselves the object of concern. Our presence is noted, our name is registered, our views are listened to, our failings are treated with indulgence and our needs are ministered to. And under such care, we flourish. There may be differences between romantic and status forms of love the latter has no sexual dimension, it cannot end in marriage, those who offer it usually bear secondary motives and yet those beloved in the status field will, just like romantic lovers, enjoy protection under the benevolent gaze of others.

It is common to describe people who hold important positions in society as somebodies and their inverse as nobodies nonsensical terms, for we are all by necessity individuals with identities and comparable claims on existence. But such words are apt in conveying the variations in the quality of treatment meted out to different groups. Those without status remain unseen, they are treated brusquely, their complexities are trampled upon and their identities ignored.

The impact of low status should not be read in material terms alone. The penalty rarely lies, above subsistence levels at least, merely in physical discomfort. It lies also, and even primarily, in the challenge that low status poses to a sense of self-respect. Discomfort can be endured without complaint for long periods when it is unaccompanied by humiliation; as shown by the example of soldiers and explorers who have willingly endured privations that far exceeded those of the poorest in their societies, and yet who were sustained through their hardships by an awareness of the esteem they were held in by others.

Next page