Introduction

E xtraordinary how a small glass bead from the island of Murano (Venice, Italy) or the mountains of Bohemia (Czech Republic) can travel around the world, entering into the cultural life of peoples far distant. Glass beads are the ultimate migrants. Where they start out is seldom where they end up. No matter where they originate, the locale that uses them makes them into something specific to their own worldview. This book is about what happens to these beads when they arrive at their final destination.

Where are beads from? Only a person from the river mouth would ask this sort of question! The Bornean bead owners reactions typically range from dont know and dont care to polite bewilderment. One very common answer is: We got the beads from our mothers, our grandmothers, our great-grandmothers. (Munan 2005: 34).

So completely have glass beads become embedded into various cultures throughout the world, that, for example, when the world thinks of Plains Indians in North America, we associate the people with their beaded buckskin clothing. We think of beadwork as a wholly American Indian art form. Again, when envisioning Samburu or Maasai women of Kenya with their many layers of beaded neckrings, we think of these neckrings as uniquely theirs.

Each cultural tradition has color preferences and its own design aesthetics and sewing techniques, so that we do not mistake Crow Indian beadwork of the American Plains with Ndebele beadwork of South Africa. Beadwork adornment conveys many culturally specific messages to those members of the group. Even so, looking at beadwork around the world reveals many parallel uses among the various beadworking societies, thus allowing the opportunity to compare the myriad of creative ways in which humankind works their beads.

This book is not actually about beads. There are many fine publications on this subject. Rather this book is about working beads resulting in beadwork , and what a collective of beads in a garment or an object reveals about the intentions of its makers or users. While these intentions arent always determined only by the beadwork, it is the bead embellishment that, working in tandem with other factors, makes clear the purposes of these objects. As Coomaraswamy (1956: 18) has observed: The beauty of anything unadorned is not increased by ornament, but made more effective by it... It is generally by means of what we now call its decoration that a thing is ritually transformed and made to function spiritually as well as physically.

Much of an objects meaning is necessarily associated with how it is used in its society. In most parts of the world, beads, having value, are often used at peak moments in life. With their luster and sparkle, used as an adornment or surface additive, they help to heighten the effect, the impact, the meaning. Beads were (and still are) called upon to adorn garments and objects, when attention is meant to be drawn to the adornee. These special moments in the adornees life tend to revolve around life stages and passages (chapters 14); power, position, or status in the community (chapters 6 and 7); the high meaning of the occasion (chapter 9); or communication with the spirits, who are attracted to the beads (chapter 8).

Fig. I.1

Bead-net dress with broad collar, 25512528 B.C.E.

Giza Tomb G7740Z, Old Kingdom, Dynasty IV, Reign of Khufu, Egypt

Faience beads

44-1/2 x 17-1/3 in. (113 x 44 cm)

Harvard UniversityBoston Museum of Fine Arts Expedition, 27.1548.12

Fig. I.2

Pfc. Eva Mirabal (Eah Ha Wa) serving in the Air Force during World War II, 1944

Photograph by AAF Air Service Command, courtesy of Jonathan Warm Day Coming

Fig. I.3

Ya-Lei Chiang, 2014

Paiwan peoples, Taiwan

Photograph by Bob Smith, courtesy of International Folk Art Alliance

Fig. I.4

Lakota Creation Narrative shirt, 2016

Maker: Thomas Red Owl Haukaas (b. 1950, Sicanu Lakota/Creole)

Wool cloth, antique glass beads

Nerman Museum of Contemporary Art, Johnson County Community College, Overland Park, Kansas, acquired with funds provided by the Barton P. and Mary D. Cohen Art Acquisition Endowment at the JCCC Foundation

A blue and green faience bead-net dress (Fig. I.1) was found in an Egyptian tomb on a female mummy during a 1927 expedition. The threads holding the beads together had disintegrated. Yet the beads and their impressions were still in place, allowing the dress to be reconstructed some 4,500 years later. This finery surely identified a woman of high status during Egypts Old Kingdom.

Faience beads were made from powdered quartz covered with a transparent blue or green glasslike coating. Not all beads used in the beadwork in this book are made of glass. Beads made from metal, cloth, stone, and other materials worked into objects served equally well to distinguish their wearer.

As Arnold Rubin (1975: 39) has stated emphatically: In a traditional context, whatever else objects may be and do, they are first of all perceived as making statements about the self-identification of their makers and users. Self- and ethnic-identity loom large in this book. Ndebele beadwork from South Africa provides a clear example of this concept. These little round imported objects [glass beads] became possibly the single most important way of publicly expressing personal or group identity as well as the deepest personal and social relationships between women and men, mothers and daughters, chiefs and commoners, elders and young men. Beadwork thus had the dual effect of transforming the wearers identities and defining relations between them. (Procter and Klopper 1994: 58). When uprooted from their territory and scattered far from other members of the Ndebele community, the women reclaimed their group identity via beadwork by reviving their distinctive beaded apparel (See chapter 2).

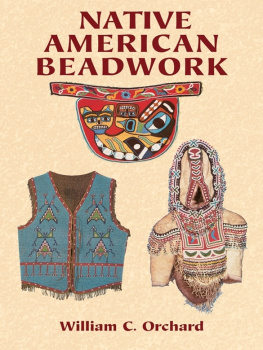

Eva Mirabal enlisted in the Womens Army Corps (WAC) in 1943, saying that since there were no sons in her Taos Pueblo family, she felt that she should join in the fight. (Gerdes 2016: 27). In this photograph (Fig. I.2) of her image in the mirror, Mirabal sees herself dressed as a WAC, yet her Lakota beaded vest shows she identifies with her Native American heritage. Moreover, even though she is a Puebloan from Taos Pueblo, not a Lakota, her pueblo has long been an important center for trade between tribes from the Plains and the Southwest United States.