The Artist Portrait Project

Copyright 2018 Jennifer G. Spencer

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, digital scanning, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law. For permission requests, please address She Writes Press.

Published 2018

Printed in Canada

ISBN: 978-1-63152-393-9 pbk

ISBN: 978-1-63152-394-6 ebk

Library of Congress Control Number: 2017964481

All photographs Jennifer G. Spencer

Artwork on pages 8, 10, 46, and 112 123rf.com

Cover and interior design by Tabitha Lahr

For information, address:

She Writes Press

1563 Solano Ave #546

Berkeley, CA 94707

She Writes Press is a division of SparkPoint Studio, LLC.

All company and/or product names may be trade names, logos, trademarks, and/or registered trademarks and are the property of their respective owners.

To those who teach art and inspire others to create.

To Suda Housesemi-retired professor of fine art, photography at Grossmont, Community College

Suda is a wonderful teacher who inspires her students to be creative with their work. Though demanding of her students, she is always supportive of a students approach to subject matter and the students learning process.

To Jim Noelretired fine art photography instructor

With more photographic history and knowledge of film, film cameras, and photo chemistry than any other instructor around, it was a pleasure and privilege to learn from this master of the analog photographic processes.

All photographs are memento mori. To take a photograph is to participate in another persons (or things) mortality, vulnerability, mutability. Precisely by slicing out this moment and freezing it, all photographs testify to times relentless melt.

SUSAN SONTAG

Photography can only represent the present. Once photographed, the subject becomes part of the past.

BERENICE ABBOTT

Contents

EpilogueIn Celebration of My Fellow Artists of San Diego:

Why photograph artists?

Foreword

The Poignancy of Portraits

Robert L. Pincus

T wenty-eight years ago, a local artist and publisher, the late Robert Perine, assembled a book called San Diego Artists. One feature of its pages was a photographic portrait of each artist selected for inclusion in a studio setting (there were fifty). Works of art have the capacity to remain perennially young, as critic Dave Hickey wisely observed in his essay Air Guitar, but photographic portraits have a different effect. They fix our attention on the passage of time; they give it tangibility, a kind of quiet intensity. Berenice Abbott, one of the twentieth centurys great photographers, expressed a similar sentiment when she remarked, Photography can only represent the present. Once photographed, the subject becomes part of the past. To this insight, I would simply add that photographs become inextricably linked to our perception of the past. We think, for example, that most people in the nineteenth century were grimmer than us because they didnt smile in pictures; but we forget that for most of the 1800s the exposure time was too long to make that even possible. Such is the power of the camera-made image. It turns the past into visual icons.

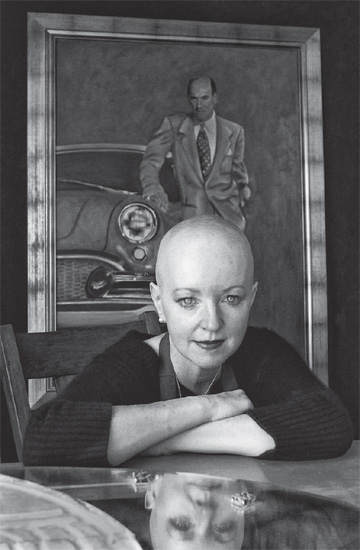

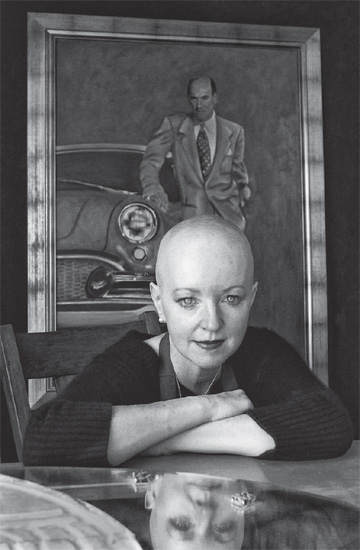

Thus, the poignancy is palpable when we look at the pictures that Perine made in the late 1980s of artists who have endured and still thrive here, such as David Avalos, Anne Mudge, Jay Johnson, and Richard Allen Morris, while others have passed away, including Italo Scanga and Ernest Silva. Still others have moved on and no longer figure in the history of art here, like Gary Ghirardi and Gillian Theobald. But there is always room for another collective portrait of San Diego artists, and I suspect Jennifer Spencers series of portraits, which she calls The Artist Portrait Project, will also acquire a large measure of poignancy with the passage of time.

Spencer has devoted a sizable amount of effort to this project, which she began in 2006. It marked a departure from her foci as a painter and an arts administrator. And while she had photographed her own work for many years, Spencer had clearly decided to elevate her ambitions with the medium of photography. After retiring from her position as executive director of the Combined Organizations for the Visual Arts (COVA) in 2002, she undertook a course of study in photography at Grossmont College. Then, having given up her large studio downtown when Petco Park moved in, she decided to launch her portrait project and devote much of her time to it.

In her role at COVA, Spencer had developed a rapport with many artists. Several of these, along with other artists she has known and admired, have become the subjects of her portraits. There are fifty in this book and, while no cross section of this number can be called fully representative of the San Diego milieu, these portraits encompass a good deal of local aesthetic territory: painters, sculptors, and photographers. There are multiple generations of them, with an emphasis on accomplished figures who have been working here for three to four decades. As Spencer aptly writes in her statement, entitled In Celebration of My Fellow San Diego Artists: Why Photograph Artists?, This project is about the persistence of the creative spirit.

In my thirty years as an art critic in San Diego, I have happily written several times about some of those she has chosen. Anne Mudge, for example, whose likeness is doubled, as if to suggest the complex nature of her sensibility and sculptures; or Victor Ochoa, looking characteristically dignified, given his role as an anchor of the local Chicano art community for decades and as a multi-dimensional muralist and educator. Spencers inviting portraits remind me that I have reviewed exhibitions or done interviews with many others she depicts: the late Walter Wojtyla, David Beck-Brown, Dana Montlack, Nilly Gill, Jeanne Dunn, John Abel, Becky Guttin, Cindy Zimmerman, and Kenneth Capps, among others. What Spencer manages to accomplish with these portraits is a keen sense of appreciation for each of these artists and a sensitivity to their different sensibilities. For Wojtyla, who had a penchant for fragmenting the figure, his portrait features something of the same effect: his seemingly disembodied head rising just above the frame of a painting that includes a head. For Montlack, whose photographic images delve deeply into the sea and its life forms, the setting is the seashore and not a studio. Here are three views of her photographing on the Windansea Beach in La Jolla, paying attention to tiny details beneath her feet, so to speak.

Viewing these images as a group, I can see that Spencer isnt trying to make some grand statement about San Diego artists, which is surely for the best. Spencer has simply crafted an appreciation, a personal chronicle of artists that matter to her. We can view and contemplate these portraits in the present tense, but they will likely have historical value as time passes. The meaning of the portraits is amplified by Spencers written diary of her sessions, and its ambitions are outlined in her statement of purpose, In Celebration of My Fellow Artists of San Diego: Why Photograph Artists? Peoples memories will fade, but the pictures and Spencers accompanying texts will endure as a sustained view of artists in our time in this city.

Next page