Published in 2016 by Enslow Publishing, LLC.

101 W. 23rd Street, Suite 240, New York, NY 10011

Copyright 2016 by Sara McIntosh Wooten

Enslow Publishing materials copyright 2016 by Enslow Publishing, LLC.

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced by any means without the written permission of the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Medina, Mariana, author.

Frida Kahlo : self-portrait artist / Mariana Medina and Sara McIntosh Wooten.

pages cm. (Influential Latinos)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

Summary: Describes the life and work of Frida Kahlo Provided by publisher.

ISBN 978-0-7660-6997-8

1. Kahlo, FridaJuvenile literature. 2. Portrait paintersMexicoBiographyJuvenile literature.

I. Wooten, Sara McIntosh, author. II. Title.

ND1329.K33M43 2015

759.972dc23

[B]

2015016463

To Our Readers: We have done our best to make sure all Web sites in this book were active and appropriate when we went to press. However, the author and the publisher have no control over and assume no liability for the material available on those Web sites or on any Web sites they may link to. Any comments or suggestions can be sent by e-mail to .

Portions of this book originally appeared in the book Frida Kahlo: Her Life in Paintings.

Photo Credits: 2015 Banco de Mxico Diego Rivera Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, Mexico, D.F. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, pp..

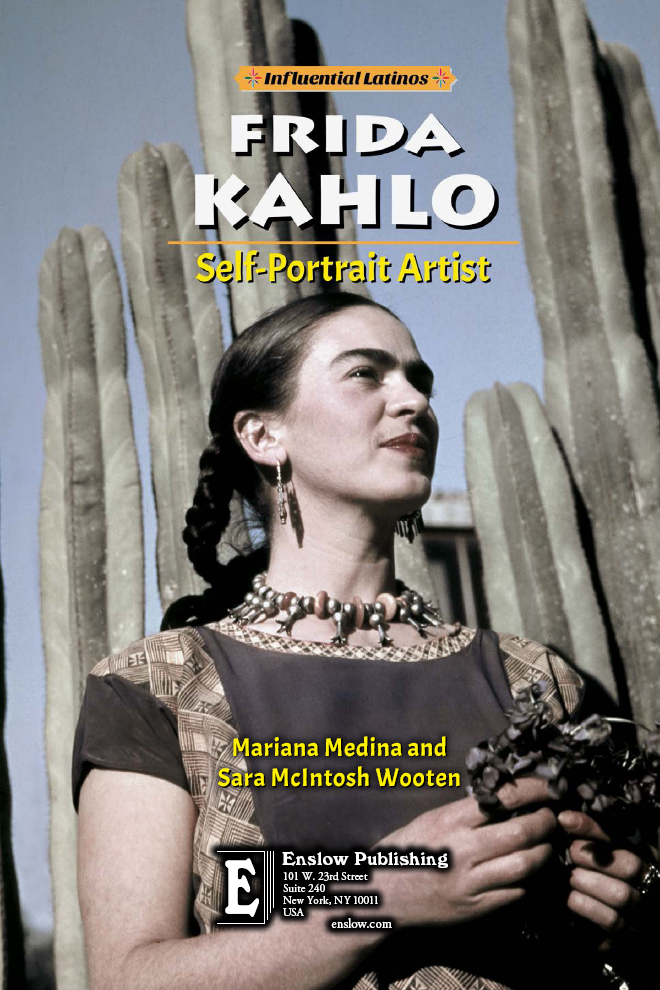

Cover Credit: Ivan Dmitri/Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images (Frida Kahlo).

Contents

First Solo Exhibition

Frida Kahlos Early Years

School Days

From Pain Comes Painting

Frida and Diego

In America

Scandals

Artistic Highs and Personal Lows

A New Acceptance

Frida Kahlos Last Years

Chronology

Chapter Notes

Glossary

Further Reading

Index

Mexican painter Frida Kahlo depicted her lifes journey in self-portraits that captured beauty and pain.

Chapter 1

FIRST SOLO EXHIBITION

O n the night of April 13, 1953, a crowd gathered outside Mexico Citys Galera de Arte Contemporneo (Gallery of Contemporary Art). Shortly after 8 p.m. the sound of sirens stirred excitement among those gathered. The sirens became increasingly louder until finally an ambulance, accompanied by a police escort, arrived. As people in the crowd craned their necks to see, the doors to the vehicle opened, and the artist Frida Kahlo was carried inside on a stretcher.

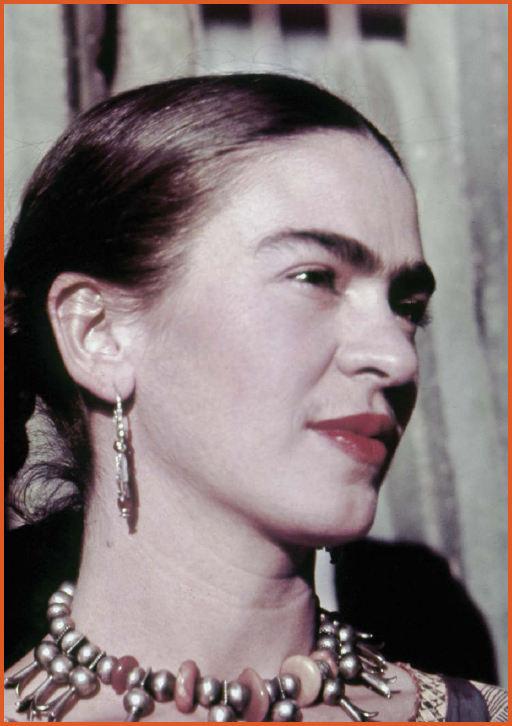

At first glance, Kahlo did not look sick. She was dressed in colorful native Mexican dress. Heavy jewelry adorned her neck. Rings of different colors flashed from each of her fingers, and her carefully painted nails gleamed bright red. Her long black hair, braided and piled on her head, was interlaced with colorful ribbons that matched her outfit.

Yet despite her festive appearance that evening, Kahlo was desperately ill and heavily medicated against pain. At forty-five years of age, she had battled illness and pain since childhood. Most recently, a series of operations on her spine had resulted in a year-long hospital stay. Even after that, her health had continued to decline, and she was frequently bedridden. Many people thought she would be too ill to attend the exhibit. Yet Kahlo ignored her doctors warnings to stay home. She refused to miss her first solo exhibition in her beloved country of Mexico.

Inside the gallery, Kahlo was carefully placed on her four-poster canopied bed, which had been installed in the center of the room. Surrounding her were hundreds of friends, family, art critics, and well-wishers. Thirty-five of her paintings and drawings were on display.

The exhibition had been organized by Kahlos friend Lola Alvarez Bravo, a photographer and the gallerys owner. She knew Kahlo was gravely ill and wanted to honor her life and work before she died. She had prepared handwritten invitations on heavy colored paper, tied with ribbons, beginning with the words:

With friendship and affection

straight from the heart,

I have the pleasure to invite you

to my humble exhibition.

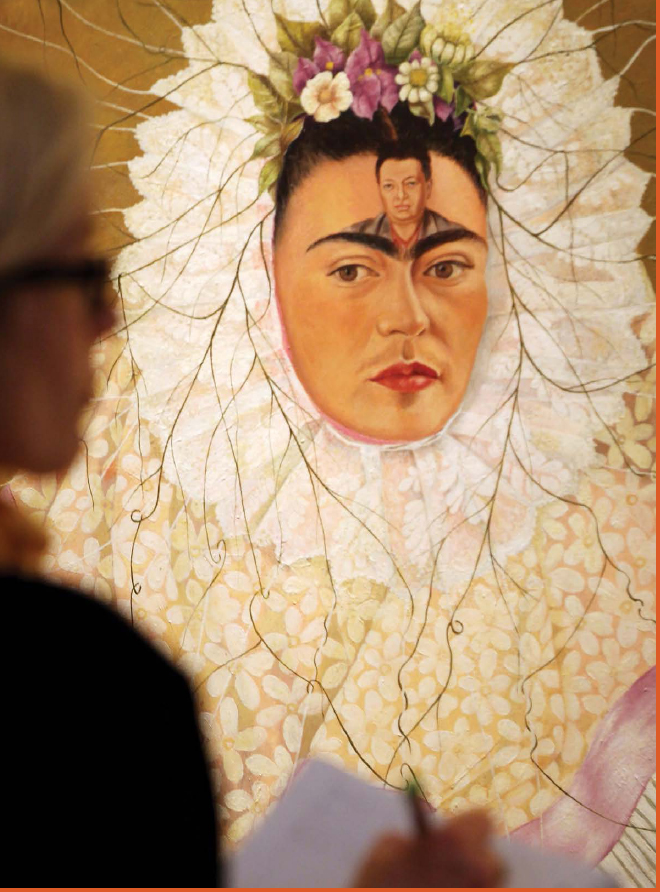

Once settled in her bed at the gallery, Kahlo greeted her guests as they gathered around to pay their respects. Those who had visited Kahlo at her home recognized the bed. A mirror attached inside the canopy allowed the bedridden artist to paint her self-portraits by simply looking up. Pictures of her friends, family, and political heroes covered the headboard, while papier-mch skeletons danced from the beds canopy.

Frida Kahlo adopted the signature look of Mexican peasant clothing, daring jewelry, thick eyebrows, and red lips.

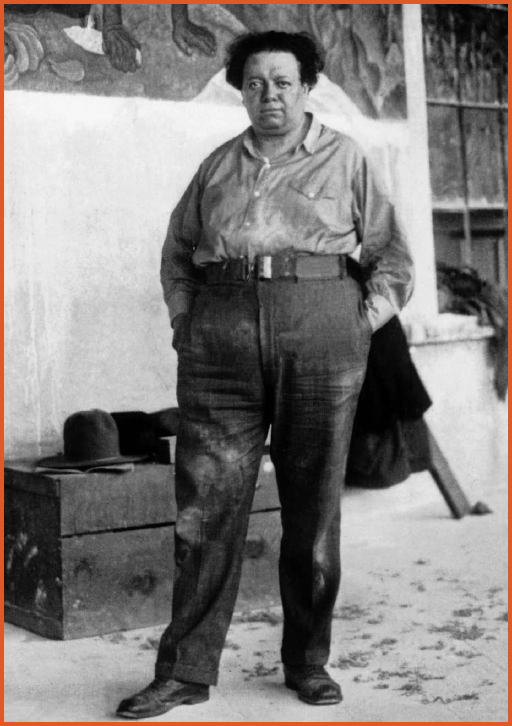

Among the guests and well-wishers that evening was Kahlos husband of almost twenty-five years, Diego Rivera. He was Mexicos most famous artist. At that time, Riveras work was far more famous than Kahlos. Yet Rivera, who had always admired his wifes work, was delighted with the success of the evening. Later, in his autobiography, he wrote, For me, the most thrilling event of 1953 was Fridas one-man show in Mexico City. Anyone who attended it could not but marvel at her great talent.

As the guests viewed the exhibition, they came face toface with Kahlos unusual style. Most of her work was of herself at various times in her life. Many paintings were quite small (12 in by 18 in, [30 cm by 46 cm]) and conveyed her psychological or physical pain at the time they were painted. Kahlo often used a primitive, almost childlike style, as a way of incorporating and honoring Mexican folk art in her work. She also used symbols and elements from Mexican history to convey her message.

Among the paintings on display was The Little Deer, which she had completed in 1946. In this painting, Kahlo portrayed herself as a deer bounding through the forest. Arrows pierce the animals body and the wounds drip blood. Looking out from under the antlers is not the face of a deerit is Kahlo. The deer, like Kahlo, is surely suffering, but the expression on the face does not show her pain.

Mexican muralist Diego Rivera was Kahlos greatest love. As artists and historical figures, they are forever connected.

Another painting, set off a bit from the other works of art, was Tree of Hope, also completed in 1946. This painting is divided vertically into a day side and a night side. Kahlo appears twice in the painting. The day side shows her lying on a hospital bed with her back exposed to the viewer. The surgical incisions from a recent operation are clearly visible. In the night side of the painting, Kahlo wears traditional Mexican dress and seems to be watching over her hospital self. In her hand she holds a medical corset, along with a flag bearing the words Tree of Hope, keep firm. She is crying, yet determined. The painting projects her as a victim as well as a survivor.