Interview by Bertram D. Wolfe

Interview by Geoffrey T. Hellman and Harold Ross

INTRODUCTION

FRIDA KAHLO: PAINTING COMPLETED MY LIFE

HAYDEN HERRERA

Frida Kahlos interviews gathered in this book are intimate conversations. Her way of talking was as lively and direct as her painting. Similarly, when she spoke, she said whatever came into her head without trying to edit her thoughts and words. Kahlo could be hilarious, she could be ribald, and she could swear like a mariachi. She sometimes expressed herself with honesty that shocked. Her paintings, too, can be shocking. They are so personal, so full of agony, and often so bloody that viewers might draw back in horror before fully taking them in.

I paint my own reality, Kahlo once said. Her art and life are so intimately linked that her work has been called an autobiography in paint. But her reality, no matter how straightforward its presentation, is always transformed by imagination. She charges actual moments with feeling and fascination by searching her core to find images that make reality more real than real. Kahlos paintings dive so deeply into the personal that their message becomes universal. With uncanny force, they emblazon themselves on the mind and eye. For that reason, her art touches people all over the world. She has become an international cult figure. The so-called Blue House where Kahlo was born and died is now the wildly popular Frida Kahlo Museum. Fridas followers go there as if they were going to a temple.

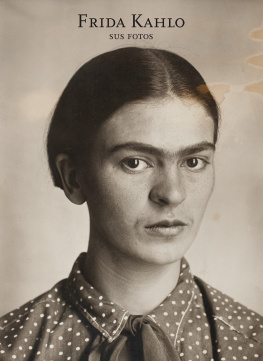

Frida Kahlo was born in 1907 in Coyoacn, then a suburb of Mexico City. Her mother was a Mexican of mixed Indian and Spanish descent. Her father emigrated from Germany to Mexico in the late 19th century and became a professional photographer. Kahlo began the story of her life with My Birth, 1932, one of the bravest images ever painted. Her naked mother is shown from the viewpoint of the midwife. Her head is covered with a sheet because, Kahlo explained, while she was at work on this painting her mother died. The head of the child emerging from her mothers womb looks dead as well. Augmenting the anguish is a painting of the weeping Madonna of Sorrows, pierced by daggers, hanging on the wall above the mother.

The story continues in My Nurse and I, 1937, where Kahlo lies in the arms of her Indian wet nurse. My mother couldnt suckle me because eleven months after I was born, my sister Cristina was born. I was fed by a nana whose breasts they washed every time I was going to suckle. Frida has the body of an infant and the head of an adult because, she said, she did not remember her nurses face. Of this, her favorite among her own works, Kahlo observed: I came out looking like such a little girl and she so strong and saturated with providence that it made me long to sleep. To Frida, this image was consoling, in part because it showed her deep connection with nature and affirmed her passion for her native roots. Yet the masked nurse does not cradle Frida in a loving protective embrace. Instead, she embodies a cruel fatalism. Kahlo has taken the traditional Madonna Caritas image of Virgin suckling Christ and changed it to express her lifelong feelings of separation and loss.

In My Grandparent, My Parents and Me, 1936, Frida, who looks about three, stands naked in the patio of the Blue House holding a ribbon that supports her family tree. Above her are her parents, their portraits taken from their wedding photograph. In the sky above her father, her German grandparents float on a cloud. Above her mother are her dark-skinned Mexican grandfather and his paler wife. Kahlo was renowned for her wit and it must have been with a laugh that the she turned this family tree into a triple self-portrait. On her mothers wedding dress is Frida as a fetus and just below that is Fridas conception. Perhaps the loop of pink ribbon in Fridas right hand is meant to look like the vaginal source of all this procreation. Even the plant beside Fridas conception is spewing forth seeds.

Several paintings of Frida at about age four show her alone in a vast, barren landscape that makes her look vulnerable and very much alone.

When she was seven Kahlo contracted polio and was isolated in her room for many months. This solitude and confinement led to an expansion of her world through fantasy. By drawing a circle with the mist from her breath on her windowpane, she escaped to the underworld where she met a make-believe friend. While she was ill, a special closeness developed between Frida and her father, who, like her, was often sick. (He suffered frequent attacks of epilepsy.) He helped his daughter to recover by encouraging different forms of exercise. When Frida was well again, she tried to hide her withered right leg by wearing several pairs of socks, but the cruelty of children gave them sharp eyes. Frida Kahlo Pata de Palo! they cried. (