Author: Gerry Souter

Confidential Concepts, worldwide, USA

Parkstone Press International, New York, USA

Victor Arnautoff

Georges Braque, Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, USA/ ADAGP, Paris

Jos Clemente Orozco, Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, USA/ SOMAAP, Mxico

Estate of Pablo Picasso/ Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, USA

David Alfaro Siqueiros, Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, USA/ SOMAAP, Mxico

Banco de Mxico Diego Rivera & Frida Kahlo Museums Trust. Av. Cinco de Mayo n2, Col. Centro, Del. Cuauhtmoc 06059, Mxico, D.F.

Image Bar www.image-bar.com

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced or adapted without the permission of the copyright holder, throughout the world. Unless otherwise specified, copyright on the works reproduced lies with the respective photographers, artists, heirs or estates. Despite intensive research, it has not always been possible to establish copyright ownership. Where this is the case, we would appreciate notification.

ISBN: 978-1-64461-777-9

Gerry Souter

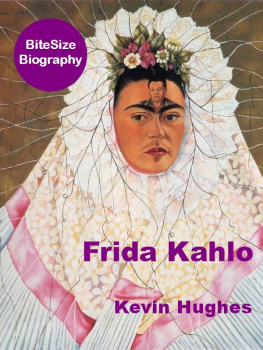

Frida Kahlo

&

Diego Rivera

Contents

Frida Kahlo

Beneath the Mirror

Introduction

Her serene face encircled in a wreath of flaming hair, the broken, pinned, stitched, cleft and withered husk that once contained Frida Kahlo surrendered to the crematorys flames. The blaze heating the iron slab that had become her final bed replaced dead flesh with the purity of powdered ash and put a period full stop to the Judas body that had contained her spirit. Her incandescent image in death was no less real than her portraits in life.

Frida Kahlo should have died 30 years earlier in a horrendous bus accident, but her pierced, wrecked body held together long enough to create a legend and a collection of work that resurfaced 30 years after her death. Her paintings struck sparks in a new world prepared to recognise and embrace her gifts.

Her paintings formed a visual diary, an outward manifestation of her inward dialog that was, all too often, a scream of pain. Her paintings gave shape to memories, to landscapes of the imagination, to scenes glimpsed and faces studied.

The painter and the person are one and inseparable and yet she wore many masks. With intimates, Frida dominated any room with her witty, brash commentary, her singular identification with the peasants of Mexico and yet her distance from them, her taunting of the Europeans and their posturing beneath banners: Impressionists, Post-Impressionists, Expressionists, Surrealists, Social Realists, etc. in search of money and rich patrons, or a seat in the academies.

And yet, as her work matured, she desired recognition for herself and those paintings once given away as keepsakes. What had begun as a pastime quickly usurped her life.

The singular consistent joy in her life was Diego Rivera, her husband, her frog prince, a fat Communist with bulging eyes, wild hair and a reputation as a lady killer. She endured his infidelities and countered with affairs of her own on three continents consorting with both strong men and desirable women.

But in the end, Diego and Frida always came back to each other like two wounded animals, ripped apart with their art and politics and volcanic temperaments and held together with the tenuous red ribbon of their love.

Her paintings on metal, board and canvas with their flat muralist perspectives, hard edges and unrepentant sweeps of local colour reflected his influence. But where Diego painted what he saw on the surface, she eviscerated herself and became her subjects.

As Fridas facility with the medium and mature grasp of her expression sharpened in the 1940s, that Judas body betrayed her and took away her ability to realise all the images pouring from her exhausted psyche. Soon there was nothing left but narcotics and a quart of brandy a day.

Frida Kahlo, The Dream or The Bed, 1940. Oil on canvas, 74 x 98.5 cm. Isidore Ducasse Collection, France.

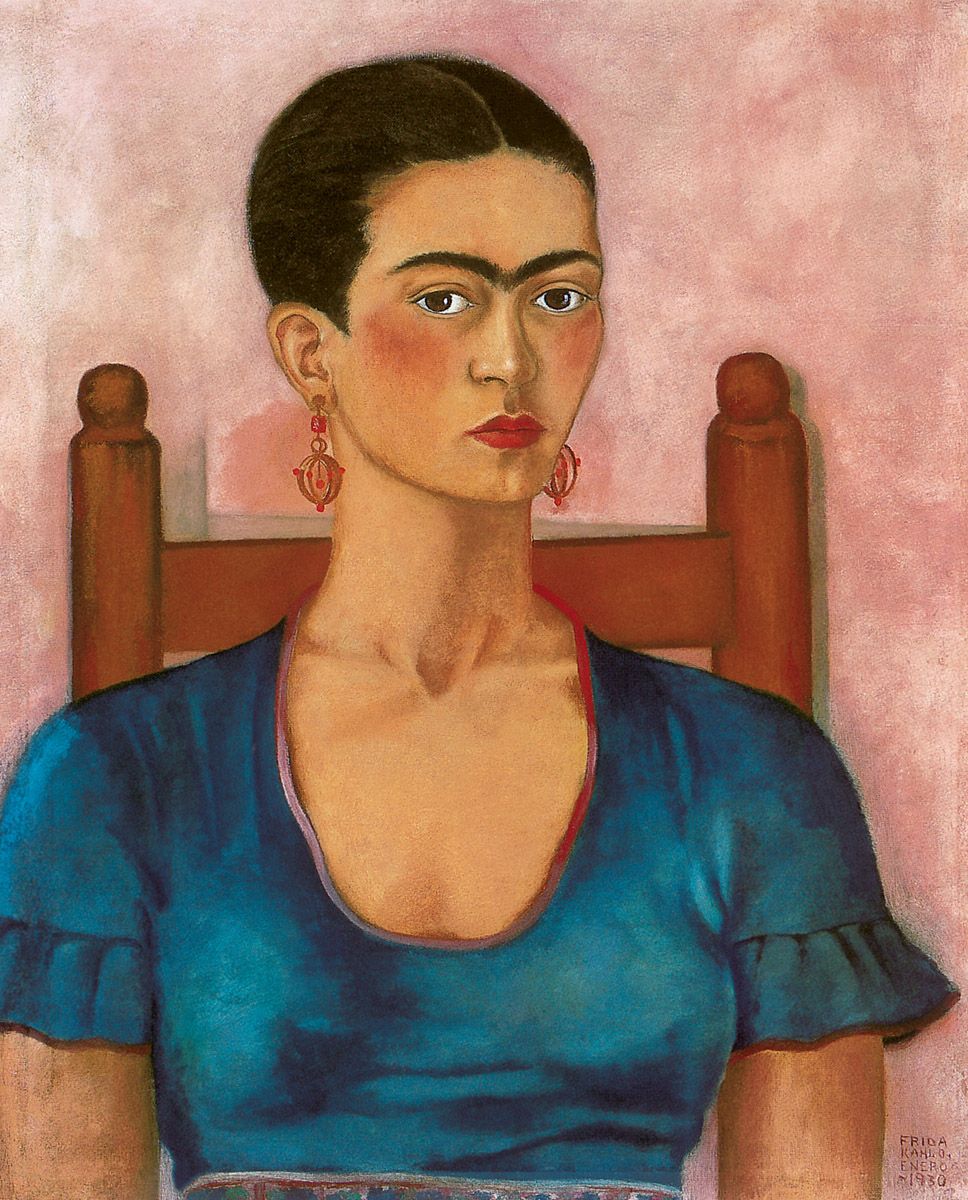

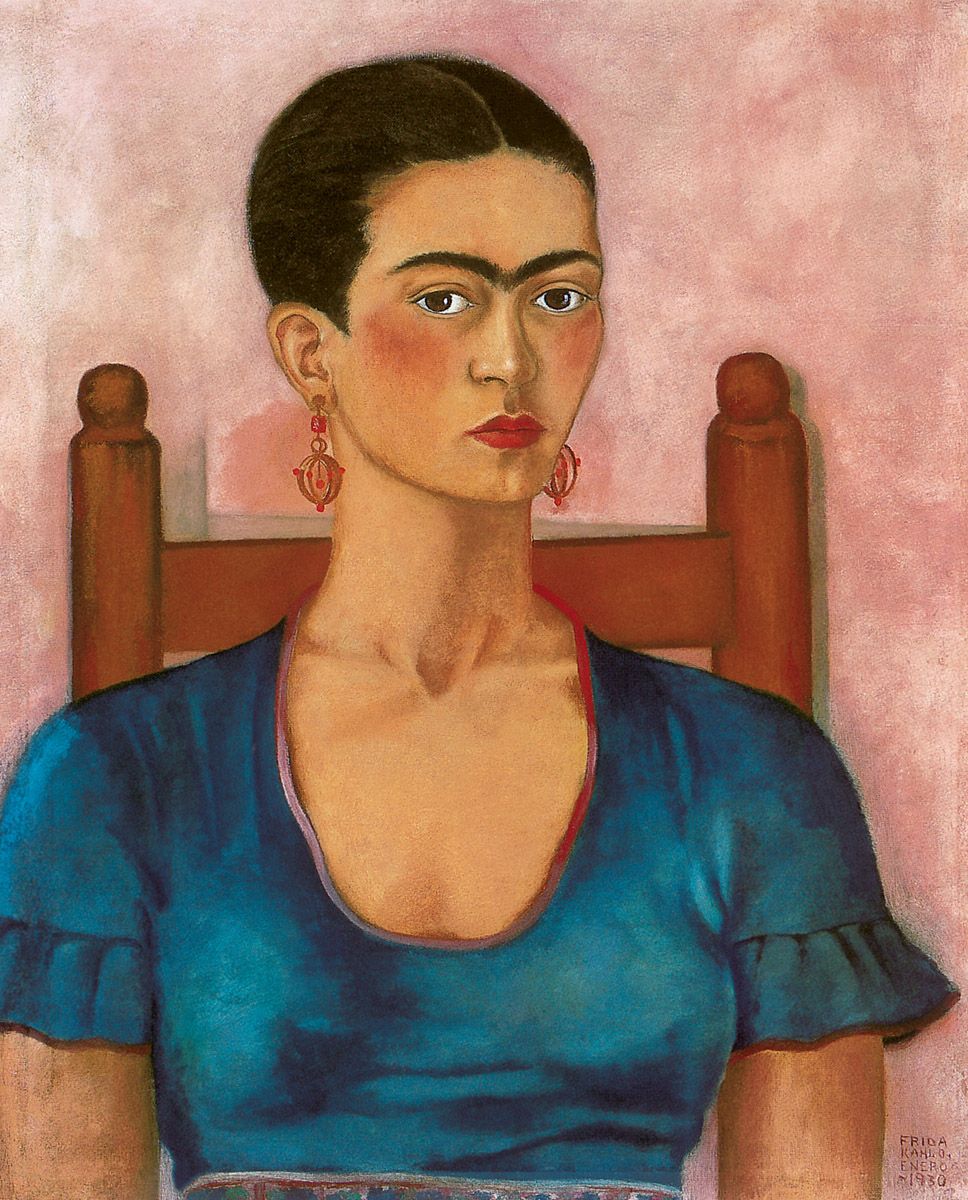

Frida Kahlo, Self-Portrait, 1930. Oil on canvas, 65 x 54 cm. Private collection, Boston.

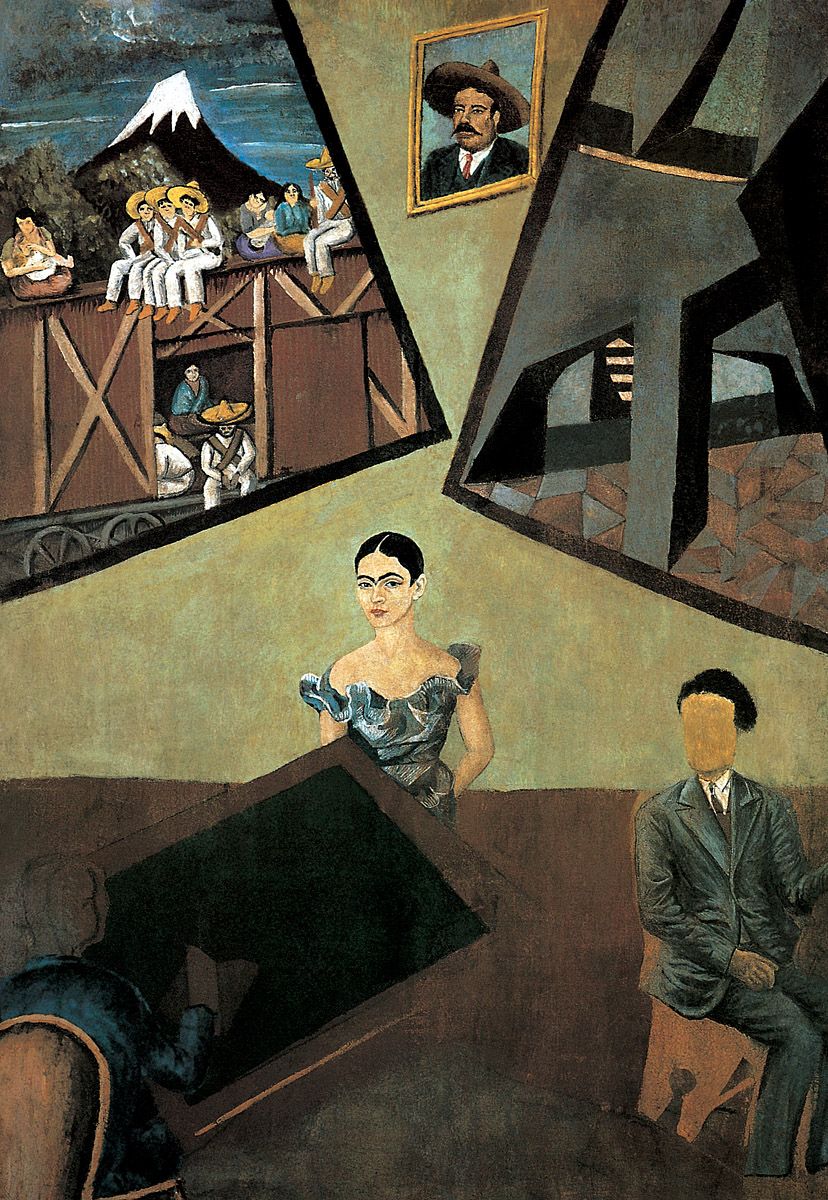

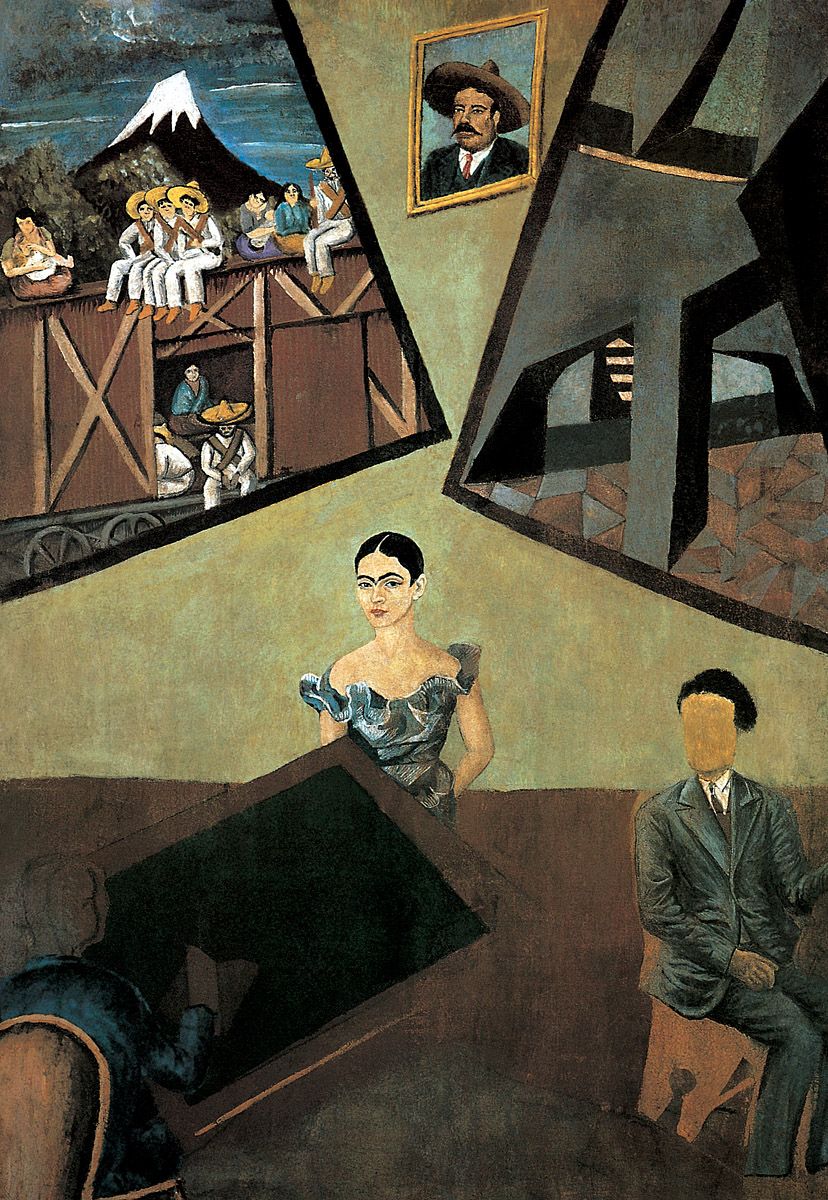

Frida Kahlo, Pancho Villa and Adelita, c. 1927. Oil on canvas, 65 x 45 cm. Gabierno del Estado de Tlaxcala, Instituto Tlaxcalteca de Cultura, Museo de Arte de Tlaxcala, Tlaxcala.

The Wild Thing

As a young girl, wherever she went she seemed to run as if there was so little time left to her and so much to be done. Magdalena Carmen Frida Kahlo y Caldern was born on July 6, 1907 in Coyoacn, Mexico. By that time running, hiding, and learning to quickly identify which army was approaching the village were everyday survival skills for Mexican civilians. Frida eventually dropped the German spelling of her name, inherited from her father, Wilhelm (changed to Guillermo), a Hungarian raised in Nuremberg. However, she used the German Frieda spelling in some of her intimate letters. Her mother, the former Matilde Caldern, a devout Catholic and a mestiza of mixed Indian and European lineage, held deeply conservative and religious views of a womans place in the world. On the other hand, Fridas father was an artist, a photographer of some note who pushed her to think for herself. Guillermo was surrounded by daughters in La Casa Azul (the Blue House) at the corner of Londres and Allende Streets in Coyoacn. Amidst all the traditional domesticity, he fastened onto Frida as a surrogate son who would follow his steps into the creative arts. He became her very first mentor that set her aside from traditional roles accepted by the majority of Mexican women. She became his photographic assistant and began to learn the trade, though with little enthusiasm for the photographic medium. She travelled with him to be there if he suffered one of his epileptic seizures.

Guillermo Kahlo was a proud, fastidious man of regular habits and many intellectual pursuits from the enjoyment of fine classical music he played almost daily on a small German piano to his own painting and appreciation of art. His work in oil and watercolour was undistinguished, but it fascinated Frida to watch him use the small brush strokes of a photo retoucher to create scenes on a bare canvas instead of just removing double chins from vain portrait customers.

He rigidly maintained his own duality: outwardly active, but trapped with his epilepsy as he regained consciousness lying in the street, felled by a grand mal seizure with Frida kneeling at his side holding the ether bottle near his nose, making sure his camera was not stolen. He played his music and read from his large library, but inside was constantly in turmoil about money to support his family. He wore what Frida described as a tranquil mask. She adopted that self-control, or at least the appearance of it, in the darkest moments of her life, never willing to display any public face that revealed what lay behind the stoic image.

Frida Kahlo was spoiled, indulged and impressionable. Her fathers success landed him a job with the government of Porfirio Daz, photographing Mexican architecture as a sort of advertisement to lure foreign investment. Since 1876 Daz had enjoyed some 30 years as president of Mexico and adopted a Darwinian philosophy toward governing the Mexican people. This survival of the fittest concept meant virtually all government money and programs went to building up the rich and successful while ignoring less productive peasants. Mexico became the economic darling of international trade as countries took advantage of its mineral wealth and cheap labour. European customs and culture ruled while native Mexican and Indian traditions languished. Daz personally selected Guillermo Kahlo to show the best side of Mexico to foreign investors, vaulting the photographer from an itinerant portraitist into the coveted middle class.