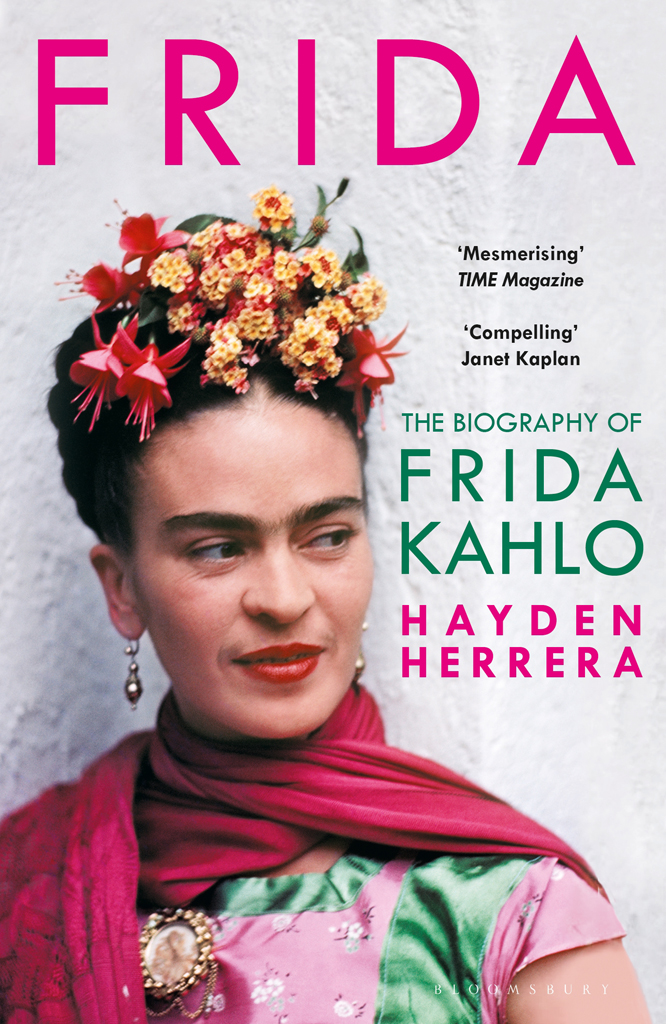

HAYDEN HERRERA is an art historian and biographer. She has lectured widely, curated several exhibitions of art, taught Latin American art at New York University, and has been awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship. She is the author of numerous articles and reviews for such publications as Art in America, Art Forum, Connoisseur, and the New York Times, among others. Her books include Mary Frank; Matisse: A Portrait; Frida: A Biography of Frida Kahlo; Frida Kahlo: The Paintings; Arshile Gorky: His Life and Work, which was nominated for the Pulitzer Prize; and Listening to Stone: The Art and Life of Isamu Noguchi, which won the Los Angeles Times Book Prize for Biography. She lives in New York City.

ALSO BY HAYDEN HERRERA

Frida: A Biography of Frida Kahlo

Mary Frank

Matisse: A Portrait

Frida Kahlo: The Paintings

Arshile Gorky: His Life and Work

Joan Snyder

Listening to Stone: The Art and Life of Isamu Noguchi

BLOOMSBURY PUBLISHING

Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

50 Bedford Square, London, WC1B 3DP, UK

BLOOMSBURY, BLOOMSBURY PUBLISHING and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

First published in Great Britain 1989

This edition published 2018

Copyright Hayden Herrera, 1983

Hayden Herrera has asserted her right under the Copyright,

Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as Author of this work.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers.

Bloomsbury Publishing Plc does not have any control over, or responsibility for, any third-party websites referred to or in this book. All internet addresses given in this book were correct at the time of going to press. The author and publisher regret any inconvenience caused if addresses have changed or sites have ceased to exist, but can accept no responsibility for any such changes.

Grateful acknowledgment is made for permission to reprint:

Excerpts from The Fabulous Life of Diego Rivera, reprinted by permission of Lyle Stuart, Inc.

Excerpts from Surrealism and Painting, by Andre Breton, translated by Simon Watson Taylor.

English translation copyright 1972 by Macdonald and Company (Publishers) Ltd.

Reprinted by permission of the publisher.

Lines from I Paint What I See in Poems and Sketches of E.B. White, by E.B. White.

Originally appeared in the New Yorker. Copyright 1933 by E.B. White.

Reprinted by permission of Harper & Row, Publishers, Inc.

The decorative sun and moon faces on the part-title and chapter-opening pages are by John Herrera.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: PB: 978-1-5266-0531-3

EPUB: 978-1-5266-0853-6

To find out more about our authors and books visit

www.bloomsbury.com and sign up for our newsletters

For Philip

CONTENTS

IN APRIL 1953, less than a year before her death at the age of forty-seven, Frida Kahlo had her first major exhibition of paintings in her native Mexico. By that time her health had so deteriorated that no one expected her to attend. But at 8:00 P.M., just after the doors of Mexico Citys Gallery of Contemporary Art opened to the public, an ambulance drew up. The artist, dressed in her favorite Mexican costume, was carried on a hospital stretcher to her four-poster bed, which had been installed in the gallery that afternoon. The bed was bedecked as she liked it, with photographs of her husband, the great muralist Diego Rivera, and of her political heroes, Malenkov and Stalin. Papier-mch skeletons dangled from the canopy, and a mirror affixed to the underside of the canopy reflected her joyful though ravaged face. One by one, two hundred friends and admirers greeted Frida Kahlo, then formed a circle around the bed and sang Mexican ballads with her until well past midnight.

The occasion encapsulates as much as it culminates this extraordinary womans career. It testifies, in fact, to many of the qualities that marked Kahlo as a person and as a painter: her gallantry and indomitable alegra in the face of physical suffering; her insistence on surprise and specificity; her peculiar love of spectacle as a mask to preserve privacy and personal dignity. Above all, the opening of her exhibition dramatized Frida Kahlos central subjectherself. Most of the some two hundred paintings she produced in her abbreviated career were self-portraits.

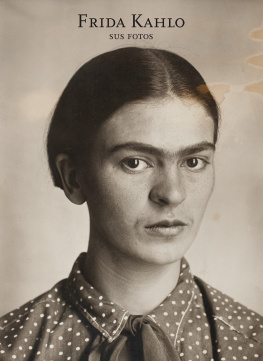

She started with dramatic material: nearly beautiful, she had slight flaws that increased her magnetism. Her eyebrows formed an unbroken line across her forehead and her sensuous mouth was surmounted by the shadow of a mustache. Her eyes were dark and almond-shaped, with an upward slant at the outer edges. People who knew her well say Fridas intelligence and humor shone in those eyes; they also say her eyes revealed her mood: devouring, bewitching, or skeptical and withering. There was something about the piercing directness of her gaze that made visitors feel unmasked, as if they were being watched by an ocelot.

When she laughed it was with carcajadas, a deep, contagious laughter that burst forth either as delight or as a fatalistic acknowledgment of the absurdity of pain. Her voice was bronca, a little hoarse. Words tumbled out intensely, swiftly, emphatically, punctuated by quick, graceful gestures, that full-bellied laughter, and the occasional screech of emotion. In English, which she spoke and wrote fluently, Frida tended to slang. Reading her letters today, one is struck by what one friend called the toughisms of her vernacular; it is as if she had learned English from Damon Runyon. In Spanish, she loved to use foul languagewords like pendejo (which, politely translated, means idiotic person) and hijo de su chingada madre (son of a bitch). In either language she enjoyed the effect on her audience, an effect enhanced by the fact that the gutter vocabulary issued from such a feminine-looking creature, one who held her head high on her long neck as nobly as a queen.

She dressed in flamboyant clothes, greatly preferring floor-length native Mexican costumes to haute couture. Wherever she went she caused a sensation. One New Yorker remembers that children used to follow her in the streets. they would ask; Frida Kahlo did not mind a bit.

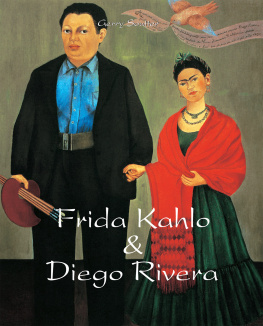

In 1929 she became the third wife of Diego Rivera. What a pair they made! Kahlo, small and fierce, someone out of a Gabriel Garca Mrquez novel, if you will; Rivera, huge and extravagant, straight out of Rabelais. They knew everybody, it seemed. Trotsky was a friend, at least for a while, and so were Henry Ford and Nelson Rockefeller, Dolores del Rio and Paulette Goddard. The Rivera home in Mexico City was a mecca for the international intelligentsia, from Pablo Neruda to Andr Breton and Sergei Eisenstein. Marcel Duchamp was Fridas host in Paris, Isamu Noguchi was her lover, and Mir, Kandinsky, and Tanguy were admirers. In New York she met Stieglitz and Georgia OKeeffe, and in San Francisco she was photographed by Edward Weston and Imogen Cunningham.

Thanks to Riveras mania for publicity, the Rivera marriage became part of the public domain; the couples every adventure, their loves, battles, and separations, were described in colorful detail by an avid press. They were called by their first names only. Everybody knew who Frida and Diego were: he was the greatest artist in the world; she was the sometimes rebellious priestess in his temple. Vivid, intelligent, sexy, she attracted men (and took many as lovers). As for women, there is evidence that she had lesbian liaisons too. Rivera did not seem to mind the latter, but objected strenuously to the former. he said, and threatened to shoot one interloper with his pistol.