Frida Kahlo

Titles in the series Critical Lives present the work of leading cultural figures of the modern period. Each book explores the life of the artist, writer, philosopher or architect in question and relates it to their major works.

In the same series

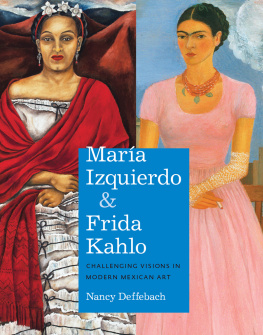

Georges Bataille Stuart Kendall Charles Baudelaire Rosemary Lloyd Simone de Beauvoir Ursula Tidd Samuel Beckett Andrew Gibson Walter Benjamin Esther Leslie John Berger Andy Merrifield Jorge Luis Borges Jason Wilson Constantin Brancusi Sanda Miller Charles Bukowski David Stephen Calonne William S. Burroughs Phil Baker John Cage Rob Haskins Fidel Castro Nick Caistor Coco Chanel Linda Simon Noam Chomsky Wolfgang B. Sperlich Jean Cocteau James S. Williams Salvador Dal Mary Ann Caws Guy Debord Andy Merrifield Claude Debussy David J. Code Fyodr Dostoevsky Robert Bird Marcel Duchamp Caroline Cros Sergei Eisenstein Mike OMahony Michel Foucault David Macey Mahatma Gandhi Douglas Allen Jean Genet Stephen Barber Allen Ginsberg Steve Finbow Derek Jarman Michael Charlesworth Alfred Jarry Jill Fell James Joyce Andrew Gibson Franz Kafka Sander L. Gilman Frida Kahlo Gannit Ankori Lenin Lars T. Lih Stphane Mallarm Roger Pearson Gabriel Garca Mrquez Stephen M. Hart Karl Marx Paul Thomas Edweard Muybridge Marta Braun Vladimir Nabokov Barbara Wyllie Pablo Neruda Dominic Moran Octavio Paz Nick Caistor Pablo Picasso Mary Ann Caws Edgar Allan Poe Kevin J. Hayes Ezra Pound Alec Marsh Marcel Proust Adam Watt Jean-Paul Sartre Andrew Leak Erik Satie Mary E. Davis Arthur Schopenhauer Peter B. Lewis Gertrude Stein Lucy Daniel Richard Wagner Raymond Furness Simone Weil Palle Yourgrau Ludwig Wittgenstein Edward Kanterian Frank Lloyd Wright Robert McCarter

Frida Kahlo

Gannit Ankori

REAKTION BOOKS

For my father, Zvi, and my mother, Ora, who took me to Mexico when I was a little girl and taught me to passionately embrace love, life and art.

Published by Reaktion Books Ltd

33 Great Sutton Street

London EC1V 0DX, UK

www.reaktionbooks.co.uk

First published 2013

Copyright Gannit Ankori 2013

All rights reserved

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers.

Page references in the Photo Acknowledgments and

Index match the printed edition of this book.

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Bell & Bain, Glasgow

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

eISBN: 9781780232225

Contents

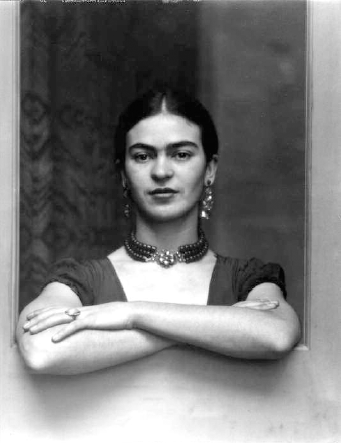

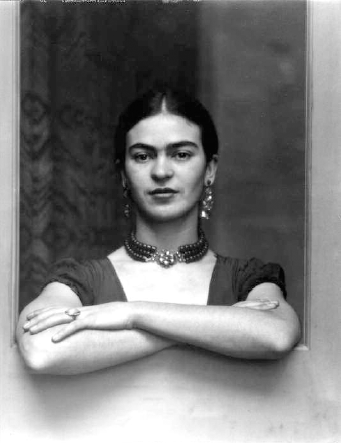

Frida Kahlo in San Francisco, photo by Peter Juley, 1931.

Introduction: The Artist as Mythmaker; Fissured Tales of Art and Life

Who knows anything of LIFE?

Frida Kahlo

In a series of interviews that Frida Kahlo dictated to Olga Campos in the autumn of 1950, the tired and disillusioned artist professed:

I do not like to influence others.

I would not like to become famous.

I have done nothing deserving of acknowledgment in my life.

When Kahlo made this statement she had already produced virtually all the iconic paintings for which she is well known indeed, venerated today.

Ten years earlier, when still in her prime, Kahlo had expressed a comparable sense of worthlessness in a heart-rending letter to her then estranged husband, Diego Rivera. In a brutally self-critical epistle, she offered a succinct summary of her life as a series of personal and professional disappointments and utter failures:

The conclusion Ive drawn is that all Ive done is fail. When I was a little girl I wanted to be a doctor and a bus squashed me. I live with you for ten years without doing anything in short but causing you problems and annoying you. I began

Given Kahlos immense posthumous influence, the cult-like adulation and critical acclaim she inspires, and the current insatiable and passionate demand for her (by now priceless) paintings, such negative self-assessments regarding her own accomplishments ring not merely incorrect, but also ironic and tragic.

The chasm that separates our contemporary admiration and high regard for Kahlo and her achievements from the artists own scathing self-denigration is but one of numerous gaps and contradictions that riddle the story indeed stories of Frida Kahlo. This book is informed by the acute realization of the existence and persistence of such discrepancies.

There is an important distinction, as well as a strong reciprocal relationship, between Frida Kahlos art and her life. For those who are fascinated by the dramatic highlights of her biography a near-fatal bus accident at the age of eighteen; a stormy, on-again off-again relationship with the celebrity artist Diego Rivera; and her untimely death, after years of illness, at the age of 47 her art is merely one of many facets of this womans extraordinary existence, a useful key for understanding the story of her life. For those who are driven by a desire to decipher the meaning of Kahlos paintings, her biography provides a crucial, though not exclusive, iconographical key.

The proliferation of biographical (some would say hagiographical) studies on Kahlo and the bellowing rise of Fridamania prompted the art historian Lynne Cooke to lament that, in the case of Kahlo (like that of Van Gogh before her), a (con)fusion between the art and the life is likely to continue to dominate both the research literature and the popular imagination.art and life reveals that it is not a recent phenomenon, nor is it a result of the posthumous waves of Fridamania. Rather, although exacerbated by Kahlos recent popular appeal, it started during the artists lifetime and was, at least partially, self-created.

Surprisingly, the fascination with Kahlos life began even before she had produced, let alone exhibited, her mesmerising self-portraits. Kahlo attained her initial celebrity in 1929, after marrying the famous and infamous Diego Rivera. She was 22; he was 43. She was just barely beginning to paint; he was internationally renowned as an artist of genius, a peer and friend of Picasso, an outrageous personality and a reckless womanizer. Their 1929 marriage certificate identifies him as artist, painter and her as housewife.

Helen Appleton Reads article published in the Boston Evening Transcript on 22 October 1930 is typical. The lengthy article introduces Diego Rivera as Mexicos most celebrated painter and proceeds to discuss, as the verbose title promises, the Mexican Renaissance in Art: Diego Rivera Heads Group of Painters Who Are Rewriting Mexican History from the Revolutionary Standpoint. Midway through the article, under the subheading Native Costume, Read devotes a brief yet telling paragraph to Kahlo:

Frida, Diegos beautiful young wife, is a part of the picture. She wears the native costume, a tight-bodied, full-skirted muslin dress, the classic rebozo draped about her shoulders and a massive string of Aztec beads about her slender brown throat. She, too, is an artist and has her studio next [to] her husbands. She has a charming, nave talent and is only another example of the spontaneous artistic expression inherent in the Mexican temperament.