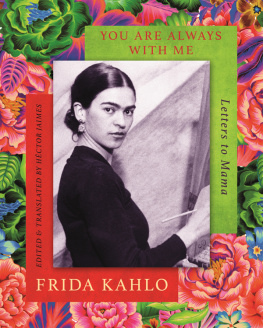

YOU ARE ALWAYS WITH ME

LETTERS TO MAMA 19231932

FRIDA KAHLO

EDITED, TRANSLATED AND INTRODUCED BY HCTOR JAIMES

VIRAGO

First published in Great Britain in 2018

by Virago Press

Copyright 2018 Banco de Mxico

Diego Rivera & Frida Kahlo Museums Trust,

Av. 5 de Mayo No. 2, Col. Centro,

Del. Cuauhtmoc C.P. 06000, Mexico City.

Translation and introduction copyright

Hctor Jaimes 2018

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this book

is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978-0-349-01194-3

Design by Andrew Barron

Virago Press

An imprint of

Little, Brown Book Group

Carmelite House

50 Victoria Embankment

London EC4Y 0DZ

An Hachette UK Company

www.hachette.co.uk

www.virago.co.uk

CONTENTS

Fridas parents, Guillermo Kahlo and Matilde Caldeon when young.

FRIDA KAHLO TOOK HERSELF AS HER SUBJECT. HER IMAGE, HER POSITION in the painting in a landscape or with people is always the heart of the matter.

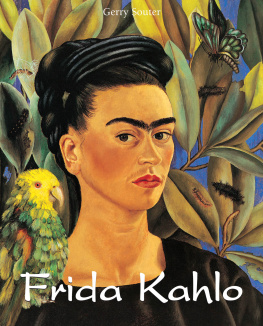

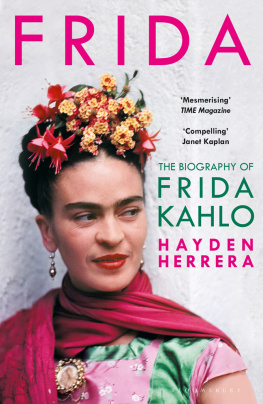

Since her first portrait in 1927 at the age of twenty, Self-Portrait in a Velvet Dress (), we see that she uses herself to represent a mood, a feeling, a truth; in essence, her sense of herself. Fridas gaze, under her famous brow, is bold and reinforced by the intensity of the colour of her burgundy dress and the tempestuous blue background.

She wrote in her diary: La revolucin es la armona de la forma y del color. Y todo est, y se mueve, bajo una sola ley: la vida. Nada est aparte de nadie. Nadie lucha por s mismo. Todo es todo y uno. La angustia y el dolor; el placer y la muerte, no son ms que un proceso para existir. La lucha revolucioinaria en este proceso es una puerta abierta a la inteligencia.

Revolution is the harmony of form and colour. And everything remains and moves under one law: life. No one is apart from anybody. Nobody struggles on his own. All is everything and one. Anguish and pain; pleasure and death, are nothing but a way to exist. In this process, the revolutionary struggle is an open door to intelligence.

As a child she suffered polio and when she was an adolescent she suffered a terrible traffic accident which resulted in psychological and physical trauma that was to remain for the rest of her life. Without a doubt these events as well as her tumultuous relationship and marriage to the Mexican mural painter Diego Rivera influenced her artistic vision.

If her paintings question identity, they also show the universality of pain and of suffering that derives from the human experience. By becoming her own artistic object Frida Kahlo transforms herself as much as she does us, as viewers. This may be why her life and art have such a capacity to win followers of diverse backgrounds; despite producing paintings that were often uncomfortable because of their violent and cruel content, we can see and feel commonalities.

Frida wrote, There have been two great accidents in my life. One was the streetcar, and the other was Diego. Diego was by far the worst. These have been the usual reference points from which to interpret her work, alongside her eccentric life, but there is much to indicate that even in her youth she displayed a restless, uncommon, creative and defiant personality.

In her diary, for example, there is not a daily or even intermittent narration of her memories or experiences but rather a non-chronological accumulation of sketches, drawings, strokes, ideas, poems and writings.

As well as keeping her diary, Frida wrote letters: a copious number to her friends, to Diego, to her doctor and to her lovers. Some of these have been published and show the woman, the wife, the lover and the artist she was.

However, until now these letters to her beloved mother, Matilde Caldern Kahlo, have not been collected and published in English.

The woman who is now recognised as one of Mexicos greatest painters was born on 6th July 1907 in Coyoacn, the third of four daughters, to a mestizo woman (of Spanish/Indian descent) and a German father, Wilhelm Kahlo, who had changed his name to Guillermo Kahlo when he had arrived in Mexico as a young man. Thanks to his wifes father, he had learned photography and at the time of the birth of Frieda spelt the German way until she changed it herself later was making his living as a professional photographer. Though Frida loved her father, she was close to her mother a fact amply demonstrated by this wonderful, brief collection of letters she wrote to her dear Mama between 1923 and her mothers death in 1932.

Frida Kahlo has become the subject of study from the perspectives of feminism, Marxism, psychoanalysis, cultural studies, sociology, art history, photography, fashion and even literature. Her work has become universal in the truest sense of the word; a universality not attained solely through her painting or her clothes or photographs but rather through the aesthetic of her lifes work including her letters.

Diego Rivera, the great painter and muralist, was her mentor, her friend and her husband. But Frida learned to distance herself from his influences and developed and created her own singular style. In Diegos Mexican period we see a wide array of historical representations of society, such as in the murals at the Secretariat of Public Education, Chapingo University or at the National Palace. Fridas works, however, are timeless. Her art, unlike her husbands, does not have a beginning or an end; hers privileges a view of the senses. It is interesting to me that Diego features Frida in his paintings as a revolutionary in arms and not, as I think of her, as a revolutionary of art. That revolutionary artistic drive and timelessness is why Kahlo has emerged the more famous artist since their deaths.

Dont be sad, because I am doing very well, Diego is very kind to me and besides, I will heal better here than in Mexico.

Surrealism has been the school of art with which Frida Kahlos works have been most commonly associated, and even though we can find some of its traits in her works she did use symbolism and allegory to transform reality her art surpasses that classification. The father of Surrealism, Andr Breton was fascinated by Fridas paintings, but his theories made her feel uncomfortable. To my mind, in the paintings by the other Mexican women painters associated with Surrealism, such as Mara Izquierdo, Rosa Rolanda, Remedios Varo and Leonora Carrington, the imaginary universe seems to take control of their paintings, while Frida Kahlos paintings invoke a deeply personal experience.

Self-Portrait in a Velvet Dress, 1927 (oil on canvas)

The archives at the Frida Kahlo Museum in Mexico City contain a large number of notes, notebooks and letters, among other materials that Frida accumulated throughout her life; from these I have selected the first eleven letters, beginning when she was aged sixteen, two years prior to her accident. She was writing to her mother when she was at school in Mexico City, eleven kilometres from her home. The other set of letters, from the archives at the National Museum of Women in the Arts in Washington, DC, were written after she was married at the age of twenty-two, when she travelled with Diego Rivera to the United States. He had been commissioned to paint murals in San Francisco (

Next page