Notting Hill Editions is an independent British publisher. The company was founded by Tom Kremer (19302017), champion of innovation and the man responsible for popularising the Rubiks Cube.

After a successful business career in toy invention Tom decided, at the age of eighty, to fulfil his passion for literature. In a fast-moving digital world Toms aim was to revive the art of the essay, and to create exceptionally beautiful books that would be lingered over and cherished.

Hailed as the shape of things to come, the family-run press brings to print the most surprising thinkers of past and present. In an era of information-overload, these collectible pocket-size books distil ideas that linger in the mind.

For Katie Ford, Gina Frangello, Emily Miles, and Sarah Sentilles, for teaching me to see and befriend this body, in all its chaos, asymmetry and imperfection.

What you say, you say in a body; you can say nothing outside of this body.

Ludwig Wittgenstein

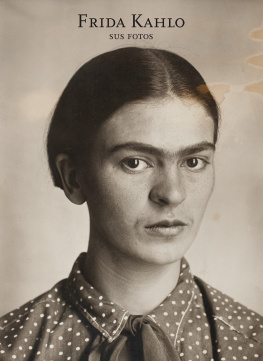

D esnudo de Frida Kahlo, a lithograph by Diego Rivera, hangs in a light-filled gallery in a small museum in Guanajuato, Mexico. In this portrait, Fridas torso is taut and slim; the sides of her waist curve inward, creating perfect hollows for each of your hands. Her breasts are soft and firm slightly lifted, because her arms are clasped behind her head; her elbows are the pointed tips of wings. The likeness is that observant, that meticulous and loving in its detail. This body is deeply known, fully seen and so elevated that you can imagine it moving into positions outside the frame, in real time and in other places. Two looped strands of large dark beads hang just below her collarbone. Her shoulders look solid, strong, able. This is a body that is loved, admired, desired. Fridas eyes are cast downward, half-shuttered as if shes in midthought. Perhaps she is enjoying her body and the adoration it evokes from her love. This extraordinary body, this remarkable image: beautiful, when she had already weathered so much.

This lithograph was made in 1930, after polio disfigured her right foot in 1913 when she was six years old; after the 1925 streetcar accident that broke her spinal column, her collarbone, her ribs, her pelvis, created eleven factures in her already weakened leg, crushed her foot and left her shoulder permanently out of joint. During the twenty-nine years between her accident and her death in 1954, Frida had thirty-two operations; was required to wear a corset every day from 1944 onward; and had her leg amputated as a result of gangrene in 1953. It was this final operation that likely led to the complications that eventually killed her. Speculation of suicide remains.

As an artist, Frida is famous for translating her pain into art, but people rarely know the full details of what she endured, and what such an enterprise of translation might require. Many of her millions of admirers across the globe do not realize that she was an amputee during that last part of her life, and that all her life her body was a canvas constantly shifting: at one point she was hung upside down to strengthen her spinal column; her body was wired and rewired, bracketed and captured and restrained and corseted in an attempt to be hemmed in, to stop her muscles and bones and joints from collapsing into chaos. She was as familiar with the edge of a scalpel as she was with the tip of a paintbrush.

Here, in Diegos 1930 likeness, her legs are thickly muscled, almost masculine. Sheer stockings hug her legs from the calves all the way to her upper thighs, stopping just short of the shaded tangle of hair between her legs. She appears soft but also invincible, a lovely live wire in careful repose. There is no invitation in her posture, only choice a reflection of the serenity and eroticism and intimate power of absolute trust; a woman who is willing to be seen by this artist, this man, fully and completely. Frida met Diego, twenty years her senior, in 1922 when she was fifteen years old. He had been commissioned to paint a mural at the National Preparatory School in Mexico City, where her program of study was meant to lead to medical school. This, one of Diegos first murals, was called Creation, and Frida walked past his larger-than-life interpretation of the beginning of the world day after day for years.

As an amputee since the age of four, I have always wondered what it would be like to have memories of two flesh and blood legs. I have always wanted someone to see me the way that Frida is seen in this lithograph. I long for a concrete, active memory of walking and running on two legs, looking at them, crossing them, spreading them, although I know this remembering would be painful. I long for the extraordinary confidence that allows Frida to be seen by the viewer without looking back to see if the body is okay, if it is offensive, if it is grotesque. But the memory of life lived on two legs is unavailable to me within the conscious process of remembering. The desired body that I long for is a fiction, and its aspiration is pointless.

When I see these legs on this womans body whose image is mounted on the wall, taken by a man who loved her; a body that will lose part of itself twenty years after it was created, a body that has already known pain as few others have known or will ever know, I feel a longing for Frida herself, for her friendship, for her guidance, and for her love, across time and culture and experience.

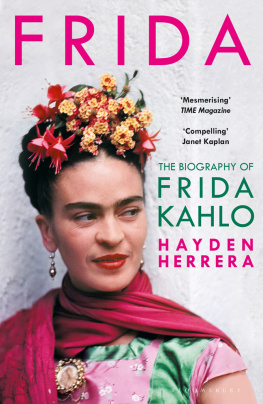

The first time I saw Fridas painting The Two Fridas (Las Dos Fridas), I felt the impact in the intimate landscape of skin between my real leg and my fabricated leg, that small, hardworking patch of flesh that touches what is connected during the day and disconnected at night. For so long I explained to people that it was like having two Emilys, living in two bodies one for the day, one for the night and when I saw The Two Fridas in an art book my brothers college girlfriend brought home during Christmas break, I thought yes. I thought you see me. I thought this is true.

It was 1991, and I was still in high school. I went to the library and found every book I could about Frida, and read them in a quiet corner as snowflakes slowly twisted to the ground on the other side of the window and the sounds of Public Enemy screeched through my Walkman headphones. Many of the books mentioned that Frida was debilitated by her pain; they talked about how much and how long she suffered. And yet, all these paintings, all this output, all this art, all this beauty. I knew that pain was not a muse, so what sustained her? The Two Fridas was not about suffering, it was about imagination and connection and that word my parents had started to use with me: self-love, which I was supposed to be practicing and was not. I had no model; I knew no female bodies like my own.

I learned later that The Two Fridas grew out of a relationship Frida developed in her mind with an imaginary friend when she was six years old, the year polio confined her to her bed. In a 1950 diary entry, she describes opening an imaginary door in her bedroom with a swipe of her hand and crossing through fields before descending to a deep place where her friend was waiting for her.

Frida Kahlo, The Two Fridas, 1939

She was agile, and danced as if she was weightless. I followed her in every movement and while she danced, I told her my secret problems. But from my voice she knew all about my affairs When I came back to the window, I would enter through the same door I had drawn on the glass. How long had I been with her? I dont know. It could have been a second or thousands of years I was happy It has been 34 years since I lived that magical friendship and every time I remember it comes alive and grows more and more inside my head.