Frida Kahlo: A Biography

I.

Frida Kahlo: A Biography

Introduction

It is impossible to separate Frida Kahlo's work from her life. This most autobiographical of artists created a virtual timeline in her paintings that spanned her entire career as an artist. From the time she began painting while recovering from a brutal accident that left her disabled, to her final struggles, shortly before her death, with a body that was literally wired together, Frida Kahlo chronicled her life on canvas. Above the gruesome aspects of her injuries, above the pain and the surgeries, rose a white hot flame of passion and creativity. When Frida Kahlo suffered, she suffered intensely; when she celebrated, her world became a celebration.

Because of the intensity of these highs and lows, the visceral effect of Frida Kahlo's work hits you with a virtual punch to the stomach. Before you realize it, you're drawn into her world, captivated by those solemn, staring portraits which, in turn, are scrutinizing you as well.

Frida's portraits depict all of life's experiences: pain, sorrow, intense suffering, and great joy. Sometimes the joy is contained and private, as in her "Wedding Portrait." Similar to Van Gogh, her paintings celebrate the simplicity and courage of everyday life; as with El Greco, her paintings also depict the universal suffering of mankind.

When we react to Frida Kahlo's work, we're reacting to Frida herself; this dynamic adds greatly to her appeal and iconic status. Perhaps no other artist since Van Gogh has evoked so much sympathy, empathy, and admiration as Frida. Yet her life was neither simply depressing nor tragic. When we think of Frida, and when we view her works, we think of both the suffering and the happiness of our lives.

Frida's art is a reflection of her life: a life well-lived to the fullest, even from its earliest beginnings.

Fridas Early Years

Perhaps by her very lineage she was destined for an exotic life full of diversity. Magdalena Carmen Frieda Kahlo y Caldern was born to a Hungarian-Jewish father (although some researchers insist he was German) and a Spanish-Mexican Indian mother on July 6th, 1907. When she was six years old, little Frida was struck by polio. She recovered, but for the rest of her life her right leg remained thinner than her left one.

Although Frida liked to cover her emaciated leg with long fiesta-style skirts and trendy mannish trousers, she never let it keep her from physical activity, and continued to be something of an adventurous tomboy. She was also a gifted scholar, and was accepted to study at one of Mexico's finest schools, the Preparatoria. Frida's first passion was medicine. Intent on a medical career, she had already begun a pre-med course in Mexico City when her first life-changing event occurred.

On September 17th, 1945, Frida was traveling on a bus when it suddenly slammed into a streetcar. For more than a year, Frida was confined to virtual immobility in bed so that her shattered body could heal. She had fractures in her spinal column, ribs, collarbone and shoulder, a crushed, dislocated right foot, 11 fractures in her right leg and a completely shattered pelvis. In addition, a huge iron handrail had pierced completely through her abdomen and uterus.

It was considered a miracle that she had even survived the accident, and equally miraculous that, after all the breakage in her body, she was able to walk again. While lying immobile, she amused herself by painting butterflies and other exotic creatures on the plaster cast that encased her torso. At one point, her photographer father, Guillermo, recalled her love of art and rigged an easel so that she could paint while lying in bed. For the greater part of a year, it became her greatest comfort and an indispensable aid to her healing.

Frida was never again to endure a day without pain. She was aware that, once she was able to walk again, she would have to adjust her life to one of less activity and physical exertion, and she made the practical decision to abandon the high-energy medical career she had at one time envisioned for herself. With her father's encouragement, she turned to her love of painting.

Fame for Frida

During the 1920s, Mexico's most acclaimed painter was the muralist Diego Rivera, whose personal life was as colorful as his paintings. As a celebrity artist, Diego represented the artistic ideal and future of Latin American art to every young painter of the era including Frida. She had been a fan of his while she was still a young student at the Preparatoria, and she used to sneak out to watch him as he worked.

Now, she remembered Rivera, and in 1927, she boldly approached him as he was painting a mural in the Ministry of Education building. She gave him four of her paintings, told him she needed to make a living as an artist, and asked him if she was talented enough to do so. Diego was immediately taken with the originality and technical dexterity of her work, and told that she had a future as a painter. In his distinguished work, Frida: A Biography of Frida Kahlo , Hayden Herrera observes that in this moment, Frida took her first step on the road to becoming one of Mexico's greatest painters.

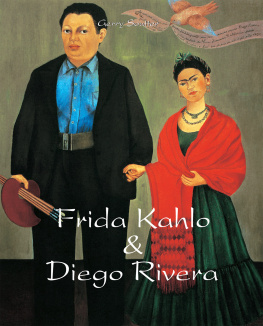

The friendship between Frida and Diego was immediate. Although he was 20 years her senior, famous and a polished artist, he felt a close kinship with her. Their outlook on art, culture and politics was the same; Diego was a popular member of Mexico's Communist Party, a group with which Frida ardently sympathized in those pre-World War II years, when many people viewed Communism as an antidote to the Fascism that was beginning to spread its roots in Europe. Although Diego was a cultured, sophisticated man he had spent much of his life living in the art world of Paris he appreciated Frida's earthiness and honesty, combined with her brilliant intelligence.

Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo were married in 1929. During the ceremony, Frida wore a simple green Mexican dress and red rebozo shawl; this costume is immortalized in Frida's "Wedding Portrait" which she completed in 1931.

During these years, Frida developed her burgeoning style, going beyond the self-portraits at which she excelled and delving into the inner core of human existence. When painting a human body, she depicted it graphically, showing heart, organs and skeleton, then linked the whole to the organism of emotional joy and pain. While many of the paintings may seem unpleasantly gory, once they're studied, the whole connected microcosm of life suddenly becomes clear. The depiction of "blood and guts" anatomy is suddenly softened by a tear in the eye, a drop of blood from the broken, bleeding heart. What seemed graphic and gory at first quickly becomes poignant. This dynamic became Frida's own autobiographical artistic style, and the running theme of many of her greatest paintings.

Scandal in America

At the time of their marriage, Diego Rivera was already well-known in the United States as a talented, highly original painter with an impeccable artistic pedigree that included friendships with artists such as Pablo Picasso. Rivera was also known for his controversial political leanings, including his membership and involvement with Mexico's Communist Party. As a free-thinker and, in the eyes of many Americans, a political radical, Rivera felt that art should represent life, and he never shied away from depicting his political convictions in his paintings.

Nevertheless, in spite of the anti-Communist sentiments of 1930s mainstream America, Diego and Frida became instant celebrities when they came to the United States in 1930. In San Francisco, Frida was invited to show her painting "Frida and Diego Rivera" at an exhibition sponsored by the San Francisco Society of Women Artists. From there, the pair traveled to New York for a special exhibition of Diego's paintings at the Museum of Modern Art, and then moved to Detroit, where Diego was commissioned to paint 27 fresco panels for the Detroit Institute of Arts.