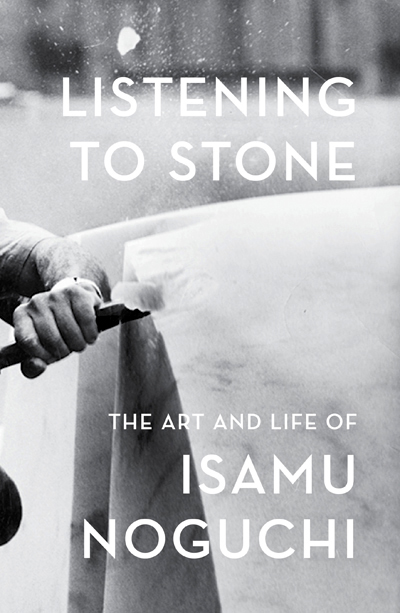

Hayden Herrera - Listening to Stone: The Art and Life of Isamu Noguchi

Here you can read online Hayden Herrera - Listening to Stone: The Art and Life of Isamu Noguchi full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2015, publisher: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, genre: Non-fiction. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Listening to Stone: The Art and Life of Isamu Noguchi

- Author:

- Publisher:Farrar, Straus and Giroux

- Genre:

- Year:2015

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

Listening to Stone: The Art and Life of Isamu Noguchi: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Listening to Stone: The Art and Life of Isamu Noguchi" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Throughout the twentieth century, Isamu Noguchi was a vital figure in modern art. From interlocking wooden sculptures to massive steel monuments to the elegant Akari lamps, Noguchi became a master of what he called the sculpturing of space. But his constant struggle-as both an artist and a man-was to embrace his conflicted identity as the son of a single American woman and a famous yet reclusive Japanese father. Its only in art, he insisted, that it was ever possible for me to find any identity at all.

In this remarkable biography of the elusive artist, Hayden Herrera observes this driving force of Noguchis creativity as intimately tied to his deep appreciation of nature. As a boy in Japan, Noguchi would collect wild azaleas and blue mountain flowers for a little garden in front of his home. As Herrera writes, he also included a rock, to give a feeling of weight and permanence. It was a sensual appreciation he never abandoned. When looking for stones in remote Japanese quarries for his zen-like Paris garden forty years later, he would spend hours actually listening to the stones, scrambling from one to another until he found one that spoke to him. Constantly striving to take the essence of nature and distill it, Noguchi moved from sculpture to furniture, and from playgrounds to sets for his friend the choreographer Martha Graham, and back again working in wood, iron, clay, steel, aluminum, and, of course, stone.

Noguchi traveled constantly, from New York to Paris to India to Japan, forever uprooting himself to reinvigorate what he called the keen edge of originality. Wherever he went, his needy disposition and boyish charm drew women to him, yet he tended to push them away when things began to feel too settled. Only through his art-now seen as a powerful aesthetic link between the East and the West-did Noguchi ever seem to feel that he belonged.

Combining Noguchis personal correspondence and interviews with those closest to him-from artists, patrons, assistants, and lovers-Herrera has created an authoritative biography of one of the twentieth centurys most important sculptors. She locates Noguchi in his friendships with such artists as Buckminster Fuller and Arshile Gorky, and in his affairs with women including Frida Kahlo and Anna Matta Clark. With the attention to detail and scholarship that made her biography of Gorky a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize, Herrera has written a rich meditation on art in a globalized milieu. Listening to Stone is a moving portrait of an artist compulsively driven to reinvent himself as he searched for his own essence of sculpture.

Hayden Herrera: author's other books

Who wrote Listening to Stone: The Art and Life of Isamu Noguchi? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.