Contents

Guide

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

For Margot and John

In the fall of 1955 Marcel Breuer, chief architect of the new UNESCO headquarters in Paris, asked Isamu Noguchi if he would design a patio for delegates. Noguchi, as was his wont, expanded the job to include an adjacent garden. The so-called Japanese Garden was a turning point in his career. Before this commission, he had, in the 1930s, been a successful portraitist, and in the 1940s his sculptures assembled out of carved and slotted stone slabs garnered the attention of critics, dealers, and museums. Early in the 1950s exhibitions and commissions in Japan made him a celebrity in his fathers country. But his UNESCO garden not only brought him the renown that would lead to major public projects in the following decades, it also taught him about the kind of sculpture he wanted to make. In his autobiography Noguchi wrote: I like to think of gardens as sculpturing of space: a beginning, and a groping to another level of sculptural experience and use: a total sculpture space experience beyond individual sculptures. A man may enter such a space: it is in scale with him; it is real.

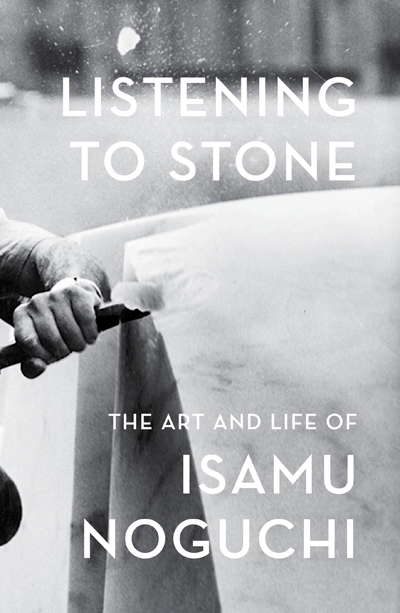

But designing this Paris garden was more than a new way of thinking about sculptural space. The two years it took Noguchi to create it were important, he said, because they had led him deeper into Japan and into working with stone. It was this attitude that, in the last two decades of his life, inspired Noguchi to spend just as much time listening to stone as carving it.

In April 1957 Noguchi traveled to Japan to look for stones for his garden in Paris. In Kyoto he met the master gardener Mirei Shigemori, who took him to a mountain area on the island of Shikoku on the Inland Sea. During two days of steady rain Noguchi clambered over wet boulders whose shining tops emerged from the current of a small brook deep in a ravine. When he found one that spoke to him, he let out a cheer from beneath his paper umbrella. He chose eighty rocksaltogether weighing some eighty-eight tons. They were, Noguchi said, very bright blue, almost too beautiful the ones I picked looked flat and light, so that perhaps you get the feeling that they [are] jumping about or happily enjoying themselves or dancing. The stonecutters who worked with him were amazed at his avidity. He was electrified by the search. What the Japanese call stone-fishing became one of Noguchis passions.

The blue stones were moved to the coast at Tokushima, where Noguchi and Shigemori spent four days moving them into an arrangement that, to Shigemoris disapproval, followed Noguchis preconceived plan. The stones would serve to punctuate space, to direct a strollers footsteps, and to offer surprise. From this time on, stone became his central passion. To search the final reality of stone beyond the accident of time, I seek the love of matter. The materiality of stone, its essence, to reveal its identitynot what might be imposed but something closer to its being. Beneath the skin is the brilliance of matter. Because stone is ancient and endures, it offered Noguchi a way of dealing with times passage.

As Noguchis enthusiasm for rock grew, he became increasingly sensitive to each stones individuality. Stones are like people. Some are more alive than others They seem to be going, you know, at another clip.

When Isamu Noguchi was a boy of ten roaming the hills above the sea in Chigasaki, Japan, he searched for wild azaleas and rare blue mountain flowers to add to the primroses, violets, and daisies that already bloomed in his garden. He persuaded a local horticulturalist to give him clippings. Soon he had about fifty rosebushes irrigated by a ditch of his own devising. And, in the Japanese fashion, he placed a rock in the garden to give a feeling of weight and permanence. When he returned home from one of his plant-searching forays with muddy feet and his mother complained, he responded, Theres such fine mud on that mountain, so rich and black and slippery. I wish we had our garden full of it.

Noguchi decided that when he grew up he would become a landscape gardener or a horticulturalist. Years later, looking back on his childhood, he attributed his passion to embed himself and his sculpture in nature to his early years in Japan. Primarily, he said, what we carry around with us is a memory of our childhood, back when each day held the magic of discovering the world. I was very fortunate to have spent my early childhood in Japan one is much more aware of nature in Japannot a vast panorama of nature but its details: an insect, a flower. Nature is very close, a foot away.

Noguchis love of gardens with moving water and carefully placed boulders would reemerge in the many gardens that he designed beginning with his 1951 Readers Digest garden in Tokyo and ending in the 1980s with California Scenario , in Costa Mesa. Driven by his feeling of placelessness, Noguchi learned to invent oases for himself and others to inhabit, places where he could calm his restless energy.

Although Noguchi maintained that it was through his gardens that he came to a reverence for stone, it is clear that his love affair with rocks began when he was a child. Stone is the fundament of the earth, of the universe, he said. Torn between East and West, Noguchi never felt that he belonged anywhere. He called himself a waif, a wanderer, a loner. He was a person for whom fierce personal attachments were rare. Rocks, on the other hand, were something he could rely on. Cutting into them with chisel and hammer was a way of merging with the earth, making it his place.

Noguchis childhood in Japan formed what he called the private side of his being.

Leonie Gilmour

Yone Noguchi never formally married Leonie Gilmour, and lived with her and Isamu only briefly. Nevertheless, Leonie thought that her son was more like his father than he was like her. In the introductory paragraph of his autobiography, published in 1968, Isamu wrote: With my double nationality and double upbringing where was my home? Where my affections? Where my identity? Japan or America, either, bothor the world? But, unlike the paintings of his contemporaries, the Abstract Expressionists, Noguchis sculptures did not explore his own identity, nor did they delve into the tumult of his subconscious. Rather, he sought to connect with the earth.

* * *

Leonie Gilmour was an extraordinarily unconventional and self-reliant woman. She was five feet three and slender with light brown, wavy hair and soft gray eyes. In photographs, wearing spectacles, she looks delicate, schoolmarmish, and charmingly Irish. Her father, Andrew Gilmour, was, according to Noguchi, an Irish Protestant who emigrated from the village of Coleraine in the far north of Ireland to America sometime in the nineteenth century. Possibly he was part of the influx of Irish immigrants fleeing the potato famine of the 1840s, although there is some evidence that he left home to escape family problems. My mother told me that he went swimming, one day in Sheepshead Bay on New Years day. Perhaps it was his grandfathers example that prompted the adult Noguchi to terrify friends by swimming far out beyond breaking waves.