ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors wish to thank the following for their assistance in writing this book:

Lynn Carson, of the Dalton Defenders Museum, Coffeyville, Kansas

Dale Chlouber of the Washington Irving Trail Museum

Dave Cooper, photographer, and Robert Rea, president, of the Franklin County Historic Preservation Society, Benton, Illinois

Jim Covell of the New Mexico Gun Collectors Association

Shelly Crittendon and Amanda Crowley of the Texas Rangers Hall of Fame and Museum, Waco, Texas

Peter Cutelli, of the St. Louis Weapon Collectors

Zac Distel and Kelly Williams of the Frazier History Museum in Louisville, Kentucky

Thomas Haggerty of the Bridgeman Art Library

Jessica Hayes and Jessica Hougen of the US Marshals Museum in Fort Smith, Arkansas

Laura Hoff, Laraine Daly Jones, Caitlin Lampman, and Rebekah Tabah of the Arizona Historical Society

Samuel Hoffman and Tom Pellegrene of the Journal Gazette in Fort Wayne, Indiana

Marguerite House of the Buffalo Bill Center of the West in Cody, Wyoming

Susan Jaffe and John Paul of Guernseys Auctions, New York

Lisa Keys and Nikaela Zimmerman of the Kansas Historical Society, Topeka, Kansas

Loren McLane of the Fort Smith National Historic Site in Fort Smith, Arkansas

Dale Peterson of the Minnesota Weapons Collectors Association

Silka Quintero of the Granger Collection

Michael Runge of the City of Deadwood Archives, Deadwood City, South Dakota, and also Rose Speirs and Carolyn Weber of the Adams Museum in Deadwood

Jason Schubert of the Davis Arms and Historical Museum, Claremore, Oklahoma

Hayes Scriven of the Northfield (Minnesota) History Collaborative

Elizabeth Van Bergen of Christies Auction House

Roy Young, editor of the Wild West History Association Journal

A special thank you to the following:

Kathie Bell of the Boot Hill Museum in Dodge City, Kansas, for the hours spent searching through the museums archives and the museum staff for taking the time to help us photograph the weapons in Boot Hills extensive collection. Also, the staff of Dodge Citys Long Branch Saloon for their help, advice, and Old West hospitality

Marguerite House of the Buffalo Bill Center in Cody, Wyoming, for her time and efforts in researching the museums database

Hans and Eva Kurth of the Cody Dug Up Guns Museum, Cody, Wyoming, for taking the time to help us photograph their unique collection

Patrick Quinn of Rock Island Auctions for his expertise, time, and encouragement providing digital images attributed to outlaws and lawmen

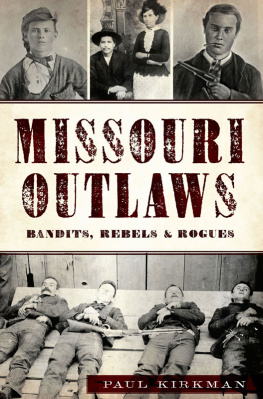

CHAPTER 1

THE OUTLAWS ARRIVE

Choose Your Weapon

I N THE NINETEENTH century, striking out to find a new start, a new life, or a new chance to grow beyond the bounds of society, which for many people rarely extended more than a hundred miles from a persons place of birth, was no less daunting than traveling to Mars. And what was the third most important thing that went into that wagon bed after the family Bible and mothers tea set? In most cases, it was a double-barreled shotgun. The shotgun was the gun that tamed the West. Nothing fancy, just a fist full of double-ought buckshot to put a jackrabbit in the stew pot, or a get-along tickle of rock salt to discourage unlawful attentions toward the familys best milk cow by four-legged crittersor two-legged thieves. It protected the flow of treasure and commerce that built towns and empires. In the hands of the law, the shotgun meant business. Held hip-high by an outlaw, it was business.

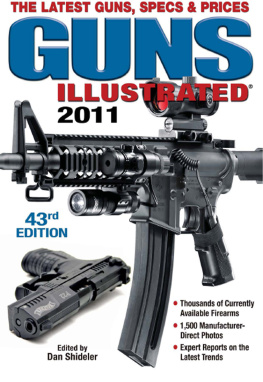

This six-gauge double-barreled breech-loading shotgun was designed for meat hunters to shoot into flocks of geese, partridge, and other game. Scatterguns were perfect for shooters with minimum practice. Rock Island Auction Company

THE FLINTLOCK

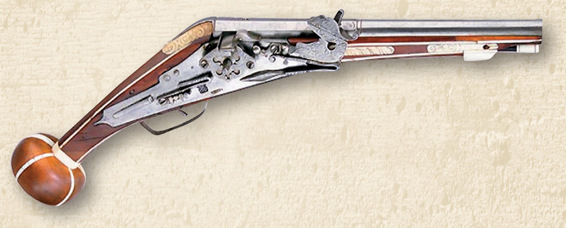

The flintlock was the natural evolution of the original Chinese fire stick, in which flame applied to compressed gunpowder caused an explosion, or rapid gas expansion, that then propelled a missile. Producing the flame was the trick. The later matchlock (or arquebus) required a cord tip saturated with saltpeter that was thrust, smoldering, into the gunpowder chamber through a touch hole. The next mechanical solution was the wheellock, which used spring-driven clockworks to spin a rough wheel against a flint to produce sparks. Finally, the gun mechanics produced an ignition spark by striking a flint against a small steel striker plate in the Dutch snaphaunce. Refining that concept created the flintlock.

Preparing the flintlock for discharge requires a measured quantity of coarse (corned) gunpowder poured down the muskets or pistols barrel followed by a ball of slightly smaller diameter than the barrels bore. The ball is wrapped in a greased linsey or cotton patch to hold it in the barrel and rammed down on top of the gunpowder charge with a ramrod that is then replaced in its ferrules beneath the barrel. A small pan at the foot of the striker plate, or frizzen, is filled with finer ground ignition gunpowder that is protected from wind or wet by a sliding panel. Thumbing the hammer (doghead) to full cock opens the pan. The tricker (trigger) is tripped with the forefinger.

The flint sweeps down, striking the frizzen and sends sparks into the priming pan, which ignites a plume of flame that squirts down into the gun powder through a touch hole. This flame ignites the powder in the barrel and the gun fires its ball, or whatever load is rammed on top of the powder. Preloaded cartridges carrying the correct powder load, ball, and patch were carried in a wood and leather box on the belt. Each cartridge was torn open, poured into the muzzle, and rammed down. The primer powder, carried in a horn or flask in a pouch or on a thong around the neck, was poured into the open pan, which was closed until ready for firing.

To fire rapidly, the rifleman tap-loads his weapon, foregoing the patch and dumping the ball down the barrel, settling it against the gunpowder by firmly tapping the gun butt against the ground and using the coarse gunpowder for both priming pan and propellant charge. This rough handling ruins accuracy and fouls the mechanism in a short time with unburned powder residue. In an emergency, however, an expert rifleman can fire four shots a minute, filling a battlefield with a hail of gunfire.

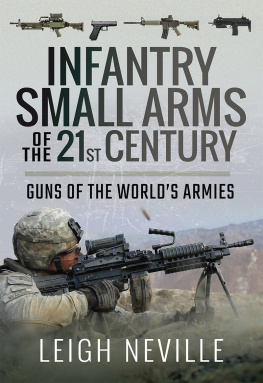

The wheellock pistol (called a dag) was a handful with all of its wood and brass furniture besides the wound-spring clockworks mechanism that spun steel teeth against a flint to produce sparks. The ball-ended grip made a dandy club. Rock Island Auction Company

The early outlaw arsenal ranged upward from the cudgel and garrote to the double-edged knife and ultimately to the flintlock pistol. During the revolution, it was a while before the Continental army began to police the vicious gangs that held open season on friends of the king, or Tories (the Tories had their own gangs as well). With colonial justice itself barely fleeing the British rope from village to town, convening courts of judgment posed a problem. As with most insurgencies, telling the zealous patriots apart from the cut-purse killers was difficult.

The flash and flame of the flintlock pistol made it the prestige weapon of choice during the Revolutionary War, even if its short barrel reduced accuracy to a handful of pacesor about forty feet. This inaccuracy in sets of dueling pistols virtually guaranteeddepending upon the distance marched offthe survival of one or both parties. Flintlock pistols were also expensive as most were made from imported parts, and they required an elaborate collection of accessories to load and clean them, which also made them slow to operate.