Contents

Copyright Yehuda Moraly, 2021.

Published in the Sussex Academic e-Library, 2019.

SUSSEX ACADEMIC PRESS

PO Box 139, Eastbourne BN24 9BP, UK

Ebook editions distributed worldwide by

Independent Publishers Group (IPG)

814 N. Franklin Street

Chicago, IL 60610, USA

ISBN 9781789760361 (Hardcover)

ISBN 9781789760880 (Paperback)

ISBN 9781782846741 (Epub)

ISBN 9781782846741 (Kindle)

ISBN 9781782846741 (Pdf)

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purposes of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This e-book text has been prepared for electronic viewing. Some features, including tables and figures, might not display as in the print version, due to electronic conversion limitations and/or copyright strictures.

Contents

Foreword by Cyril Aslanov

The concept of dream project is ontologically connected with the very essence of novel writing, play writing and movie making. Indeed, until the book is printed, the play staged, and the movie produced, every draft, every play text and every scenario may be considered nothing more than a dream project, a sketch that the lunatic author could at any minute burn, or delete from the memory of his computer. Even in our age of digitalized literary production, there is still a moment when the text ceases to be a draft: either with the printing and diffusion of the printed matter or with the virtual publication as a PDF format.

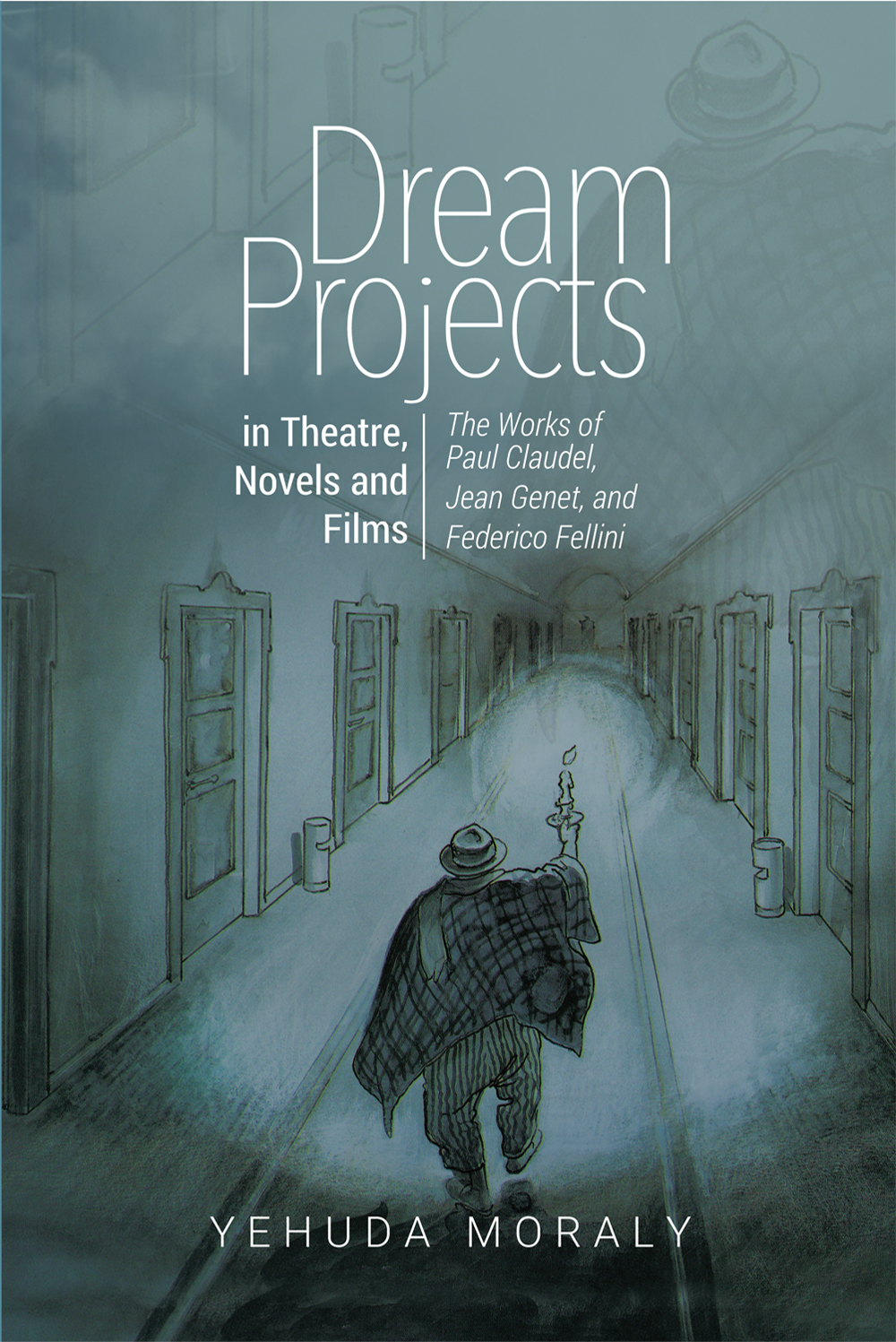

For plays, the question of the boundary between the draft and the completion of the work, something that does not belong to dream anymore, is harder to define inasmuch as the history of drama is full of plays that were written but never really destined for the stage. Claudel himself, one of the three authors with whom Yehuda Moraly deals in his Dream Projects, did not manage to see the performance of the integral version of his Soulier de satin ( The Satin Slipper ). The first attempt to stage that monstrous drama in 1943 was a considerably reduced adaptation of the whole, so that from Claudels perspective even The Satin Slipper can be considered a kind of dream project whose potential started to be actualized a long time after the authors death in 1955.

What makes Moralys study so fascinating is the fact that it bestows a semblance of existence on aborted works, leading the reader to the mental exercise of imagining what the fourth, ghost part of the envisaged Cofontaine tetralogy would have looked like, if Claudel had written it and committed it to the stage. In a certain sense Moraly helps us share the dream of the playwright who aspired to transform his trilogy into a tetralogy. The subtle difference between a real trilogy and a dream tetralogy is found later in the book, not in the chapter dedicated to Claudel, but in the chapter on Genet. There Moraly reminds us that the trilogies of the Greek dramatists are known to be in fact tetralogies. For someone like Claudel who translated Aeschyluss Tetralogy in 1894 this transformation never came about , perhaps because the intended fourth part of the projected tetralogy was far from being a satyric drama. Hence the necessity of leaving the fourth part of the tetralogy as a draft in a drawer or as a ghost part.

The boundaries between real and dreamt work are so blurred that sometimes what is overtly considered an unrealised project is in fact much closer to the reality of the tangible work than the author himself would have been able to conceive. In the second chapter of Dream projects , Moraly reaches the conclusion that Jean Genets dreamt framework La Mort ( La Mort I as a prose work and La Mort II as a series of plays) was partially fulfilled, since the tetralogy consisting of Les Bonnes, Le Balcon, Les Ngres, Les Paravents is actually a significant part of the projected La Mort II. In other words, the phantasmatic quest for the fulfilling of a dreamt work may actually lead to the emergence of a concrete work as in the case of Proust whose In Search of Lost Time speaks about the impossibility of writing a book until the last words of the seventh and final volume of the whole heptalogy ( dans le Temps ) reveal that this account of the allegedly failed attempts to write an impossible magnum opus is itself that magnum opus. Incidentally, in the second chapter of Dream Projects , Moraly stresses Genets debt to Proust who might have inspired in him also the awareness that a dream project may prove to be less dreamt than one might have expected.

The third and last panel of the triptych is a fascinating study of Fellinis phantom film Il viaggio di G. Mastorna, detto Fernet ( The Journey of G. Mastorna ), a never filmed movie projected during the years 196566. As Moraly stresses, Il viaggio di G. Mastorna is comparable to a ghost in more than one way. First of all, it is the phantasmagory of a chaotic afterlife more similar to the 1969 Fellini Satyricon than to Dantes Divine Comedy. Secondly, as Moraly convincingly demonstrates , the phantom film continued to haunt Fellinis subsequent, completed productions as an everlasting source of inspiration. It is also quite obvious that the third chapter is the centre of gravity of Dream Projects , the peak in comparison to which the first chapter dedicated to Claudels closure of the Cofontaine cycle and the second one dealing with Jean Genet La Mort I and La Mort II are only warm-up exercises.

And indeed, a re-reading of the two first chapters in the light of the third reveals that beyond the issue of dreamt plays or ghost movies, there is another leading thematic in Moralys book, namely the relationship between death and artistic creativity. This special connection between death and artistic creation is not only due to the fact that the deaths of Claudel, Genet and Fellini, respectively, interrupted their projects. In Fellinis case, especially, it has also to do with the temporary death of inspiration that affected the maestro after the tremendous successes of La Dolce vita, Le Notti di Cabiria and Otto e mezzo . However, since the failure of Il viaggio di G. Mastorna was an everlasting store of motifs and ideas for other highly successful movies in Fellinis filmography, the apparent death of inspiration could be considered as a springboard toward another phase in the Maestros career. In other words, what seems to be the death of inspiration was in fact the discovery of the potential of the idea of death as a source of living inspiration.

I would like to add a philological argument in order to reinforce the importance of the relationship between the macabre infatuation with the grotesque representation of the afterlife and the almost positive effect drawn for those gloomy phantasmagories. The key to this paradoxical reassessment of death is provided by the second name of the protagonist: Mastorna . This name that apparently sounds very Italian does not actually exist in the Italian onomasticon. However, it might sound familiar to anyone familiar with the Etruscan civilisation, or more precisely with the Etruscan substrate of archaic Rome. Indeed, Mastorna is a slight variation of Mastarna , the Latinized form of Etruscan macstarna/ macstrna , a common name whose original meaning was dictator or maybe magistrate. Whatever its signification might be, Mastarna/ Macstarna/ Macstrna was thought to be the Etruscan name for Servius Tullius, the sixth king of Rome who reigned from 575 BCE until his assassination in 535 BCE .