JEAN GENET (19101986) was born in Paris. Abandoned by his mother at seven months, he was raised in state institutions and charged with his first crime when he was ten. After spending many of his teenage years in a reformatory, Genet enrolled in the Foreign Legion, though he later deserted, turning to a life of thieving and pimping that resulted in repeated jail terms and, eventually, a sentence of life imprisonment. In prison Genet began to writepoems and prose that combined pornography and an open celebration of criminality with an extraordinary baroque, high literary styleand on the strength of this work found himself acclaimed by such literary luminaries as Jean Cocteau, Jean-Paul Sartre, and Simone de Beauvoir, whose advocacy secured for him a presidential pardon in 1948. Be-tween 1944 and 1948 Genet wrote four novelsOur Lady of the Flowers, Miracle of the Rose, Funeral Rites, and Querelleand the scandalizing memoir A Thiefs Journal. Throughout the 1950s he devoted himself to theater, writing the boldly experimental and increasingly political plays The Balcony, The Blacks, and The Screens. After a silence of some twenty years, Genet began his last book, Prisoner of Love (available as an NYRB Classic), in 1983. It was completed just before he died.

CHARLOTTE MANDELL has translated nearly fifty books from the French, including works by Guy de Maupassant, Marcel Proust, Maurice Blanchot, Jonathan Littell, and Mathias nard. She has been awarded a translation prize from the Modern Language Association and the National Translation Award in Prose. Her translation of The Magnetic Fields by Andr Breton and Philippe Soupault will be published by NYRB Poets in 2020.

JEFFREY ZUCKERMAN s recent translations from the French include Ananda Devis Eve Out of Her Ruins and The Living Days, the diaries of the Dardenne brothers, and the short stories of Herv Guibert. He is the digital editor of Music & Literature, and his writing and translations have appeared in Best European Fiction, the Los Angeles Review of Books, The Paris Review Daily, Tin House, and Vice.

THE CRIMINAL CHILD

Selected Essays

JEAN GENET

Translated from the Frenchby

CHARLOTTE MANDELL

and JEFFREY ZUCKERMAN

NEW YORK REVIEW BOOKS

New York

THIS IS A NEW YORK REVIEW BOOK

PUBLISHED BY THE NEW YORK REVIEW OF BOOKS

435 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014

www.nyrb.com

Selection copyright 2020 by NYREV, Inc.

Essays copyright 2014 by the Estate of Jean Genet; The Criminal Child copyright 1949, adame Miroir 1948, Letter to Leonor Fini and Jean Cocteau 1950, Fragments... and Letter to Jean-Jacques Pauvert 1954, The Studio of Alberto Giacometti 1957, and The Tightrope Walker 1958 by Jean Genet

The Criminal Child translation copyright 2020 by Jeffrey Zuckerman

All other translations copyright 2003 by Charlotte Mandell

All rights reserved.

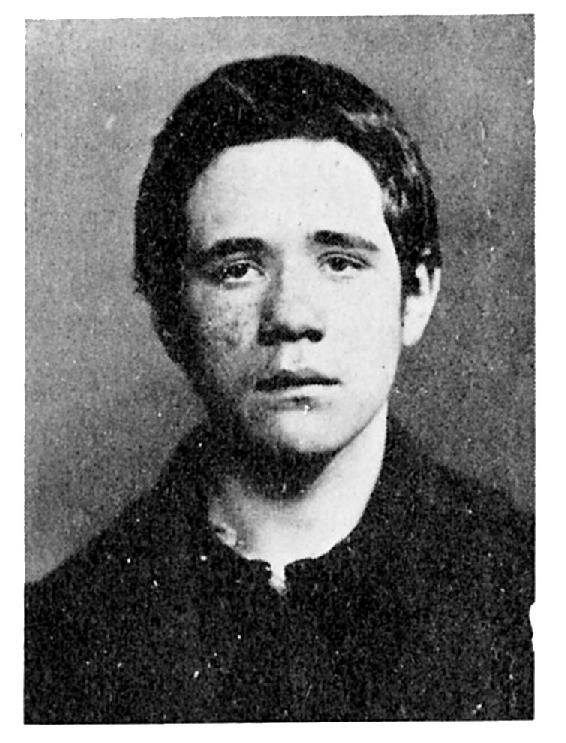

Cover image: Anonymous, photograph used on the cover of LEnfant criminel & adame Miroir, 1949

Cover design: Katy Homans

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Genet, Jean, 19101986, author.

Title: The Criminal child : selected essays / by Jean Genet ; translated by Jeffrey Zuckerman and Charlotte Mandell.

Other titles: Enfant criminel. English

Description: New York : New York Review Books, [2019] | Series: New York Review Books Classics

Identifiers: LCCN 2019013970 (print) | LCCN 2019017486 (ebook) | ISBN 9781681373621 (epub) | ISBN 9781681373614 (alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Juvenile delinquency.

Classification: LCC HV9071 (ebook) | LCC HV9071.G413 2019 (print) | DDC 364.36dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019013970

ISBN 978-1-68137-362-1

v1.0

For a complete list of titles, visit www.nyrb.com or write to:

Catalog Requests, NYRB, 435 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014

CONTENTS

I hope youll understand and forgive the emotion I feel as I tell you about an adventure of mine. As you are a mystery to me, I must confront you with, and reveal to you, the mystery of prisons for children. Scattered throughout the French countryside, often in the most elegant places, are sites that for me hold inexhaustible fascination: those correctional institutions now officially, and rather genteelly, given such names as Moral Rehabilitation Facility, Reeducation Center, Home for the Rectification of Delinquent Youths, etc. These changes of name are not insignificant. Reformatory and, sometimes, Penitentiary had become something like proper names or, more specifically, had come to name the purest, cruelest places in the depths of a childs heart, and now educators have drained as best they could these names of their violence. But it is my hope that, despite the pitifully hygienic character of these new names, children will secretly continue to be drawn to the lure of Penitentiary and Prison, even though these now exist on a moral plane rather than as a given space. How foolish to have tried to attack an idea by changing its name when the thing named is, if I may go so far, alive, set in motion solely by the actions, solely by the comings and goings of that most fruitful element: delinquent children. Criminal children. I want to repeat that the reflection or, rather, the image of these places whose names Ive recited above blaze in the souls of such children. I will come back to this.

Saint-Maurice, Saint-Hilaire, Belle-Isle, Eysse, Aniane, Montesson, Mettray: these names may not be meaningless to you. In the eyes of children who have committed a crime or offense, they embody all that, for a definite stretch of time, lies in store for them.

Theyve sentenced me to the twenty-one, they say.

These children are committing an (intentional) error, the tribunal having passed a judgment such as: Acquitted for having acted without full awareness, and entrusted to the reformatory until the age of majority... But the young criminal immediately rejects the indulgence and concern of a society that he has, in committing his first offense, revolted against. At fifteen or sixteen or earlier yet, he has attained a maturity that others may not reach even at sixty, and he scorns their munificence. He insists that his punishment be unsparing. He insists that the terms of his sentence manifest decided cruelty, and when he protests that it is they who have acquitted him, they who have handed down so mild a punishment, he does not say so without shame. He wants severity. He insists on it. Deep down he dreams of this severity as a terrible hell, of the correctional facility as a place from which he will never come back. And its true, nobody ever does come back. Those who emerge are changed. Theyve gone through the flames. And the names mentioned above arent mere names: theyre charged with meaning, burdened with a horror that the children embrace, for these names serve as the proof of their violence, their vigor, their virility. It is this severity that these children will conquer, and they insist on being tested terribly. The better to finally exhaust their restless hunger for heroism.

When I was a child, Mettray was one of the most prestigious names. But Mettray has gone to seed at the hands of some softhearted imbecile, and it is now, I gather, an agricultural colony. It was a harsh place back then. Upon arriving at this fortress of bay trees and flowersMettray wasnt walled offthe young outlaw, henceforth to be known as a colonist, underwent a thousand ordeals that would prove his true criminality. He was locked up in a cell that was painted all in black (even the ceiling). He was dressed in a outfit that for miles around was a symbol of the dreadful and ignominious. And as long as his confinement continued new ordeals lay in store for him: fights, sometimes deadly, that the guards let run their course; dormitory hammocks; enforced silences during work and mealtimes; bizarrely intoned prayers; barracks punishments; clogs; burned feet; forced marches under the noon sun; mess tins of cold water; and so on. We suffered all that at Mettray, and these miseries were echoed a hundredfold by the tortures of the Belle-Isle well, and, in other colonies, of the pit, the grave, the empty mess tin, the barracks, the latrines, and solitary confinement.

Next page