Contents

Landmarks

Page List

Editor: Howard W. Reeves

Designer: Anderson Newton Design

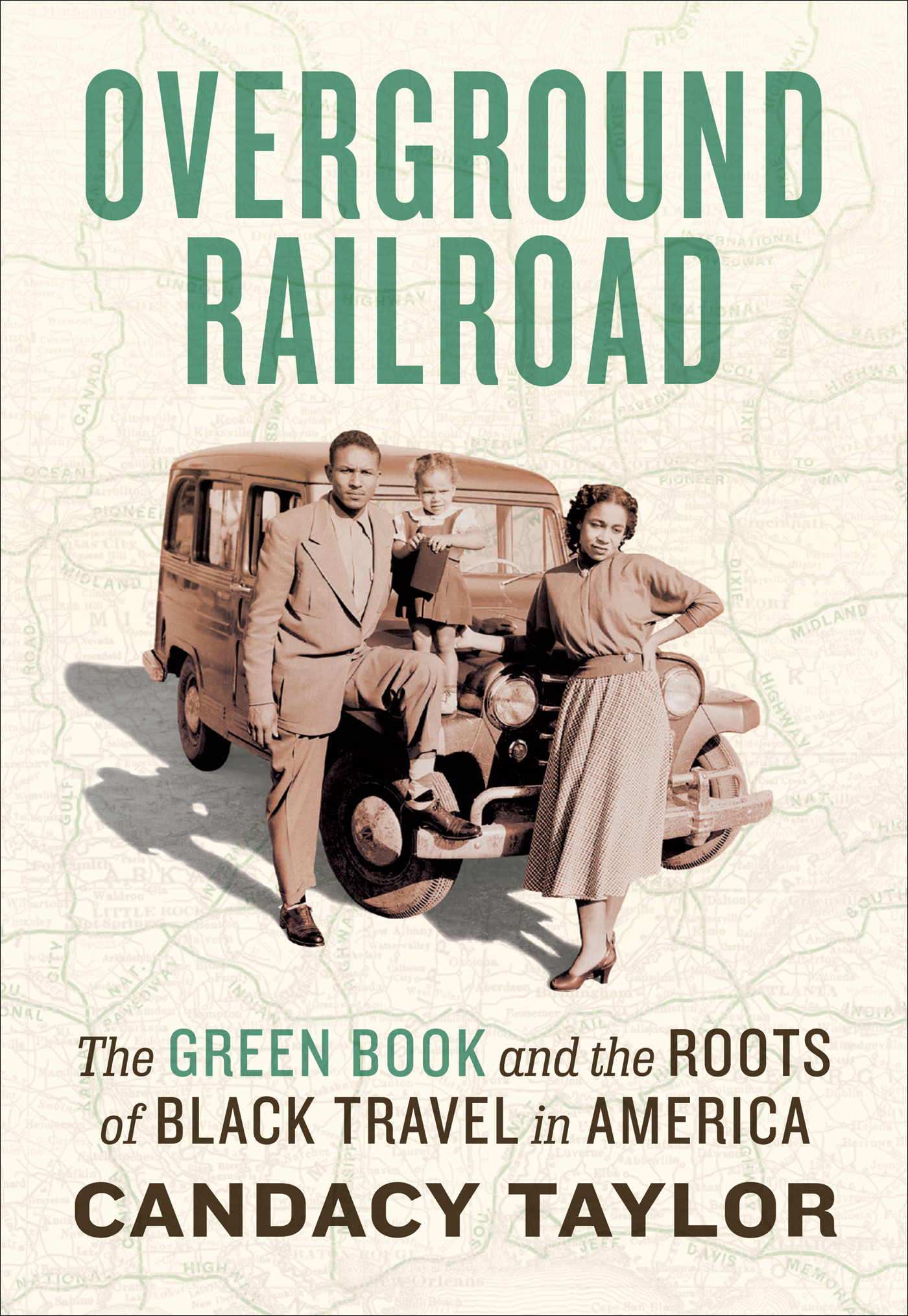

Copyright 2020 Candacy Taylor

For photo credits, see

Cover 2020 Abrams

Published in 2020 by Abrams Press, an imprint of ABRAMS. All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, mechanical, electronic, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without written permission from the publisher.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2018958273

ISBN: 978-1-4197-3817-3

eISBN: 978-1-68335-657-8

Abrams books are available at special discounts when purchased in quantity for premiums and promotions as well as fundraising or educational use. Special editions can also be created to specification. For details, contact specialsales@abramsbooks.com or the address below.

Abrams Press is a registered trademark of Harry N. Abrams, Inc.

ABRAMS The Art of Books

195 Broadway

New York, NY 10007

abramsbooks.com

For Ron, Mom, Aimee, Adger, Sophie, and Chris

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

ARE WE THERE YET?

DRIVING WHILE BLACK

The BUSINESS of the GREEN BOOK

The FIGHT

A LICENSE to LEAVE

ALL ABOARD

VACATION

MUSIC VENUES

The ROOTS of ROUTE 66

WOMEN and the GREEN BOOK

A CHANGE Is GONNA COME

INTEGRATION and the DOUBLE-EDGED SWORD of PROGRESS

EPILOGUE

AMERICA AFTER the GREEN BOOK

INTRODUCTION

ARE WE THERE YET?

Dont you dare say a word. Ron was sitting in the back seat as his father pulled the car to a stop at the side of the road. His father had told him to be quiet before, but this was the first time Ron felt the words reverberate to the pit of his stomach. Moments later, the sheriff stood over the well-appointed 1953 Chevy sedan complete with all the modern features you read about in the magazines.

Where did you get this vehicle? What are you doing here? And who are these people with you? the sheriff asked.

Rons father answered, Its my employers car. He pointed to his wife, sitting upright and expressionless in the passenger seat. He pretended that she wasnt his wife and said, This is my employers maid, and that is her son in the back. Im taking them home.

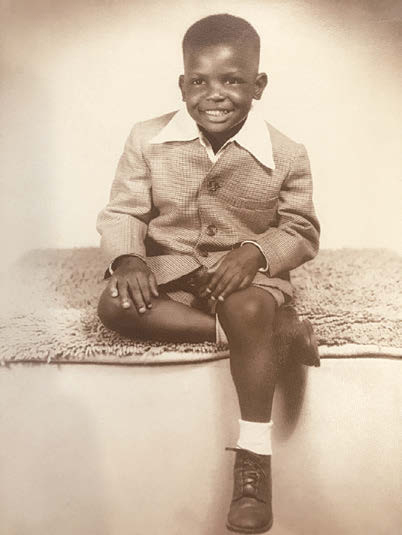

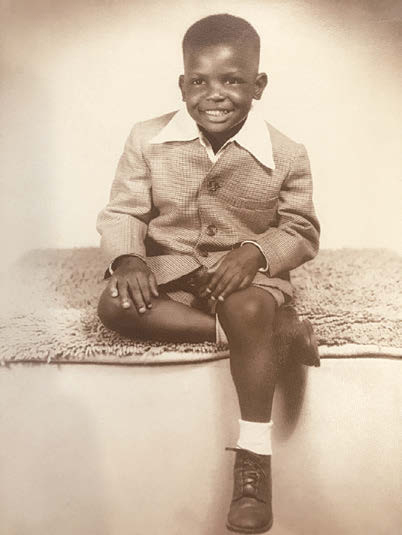

Ron at age seven

The sheriff took a long, hard look at Rons mother and then angled his eyes to the back seat. A young Ronald sat tight-lipped, too afraid to turn his head or even take a breath. Wheres your hat? the sheriff barked at Rons dad.

Hanging up right behind me in the back seat, officer.

The sheriff waved. All right. Move on.

As they drove north across the Tennessee border, a sad, eerie silence hung in the air. The jovial conversation they were having right before the sheriff pulled them over had stopped dead. And although there was no discussion about what had just happened, the gravity of the situation was clear. Ron watched Daddy and Mama exchange knowing glances and then turned his head to look at the black, unassuming cap that had been hanging next to him in the back seat ever since he could remember. It wasnt until that moment that he realized why he had never seen his father wearing it. Mama wasnt a maid, and Daddy wasnt a driver. He had a good job with the railroad, and this was their family car. Until that day, Ron never paid attention to that cap, but now he realized that it wasnt just any hat. It was a chauffeurs hat. A ruse, a propa lifesaver.

During the Jim Crow era, the chauffeurs hat was the perfect cover for every middle-class black man pulled over and harassed by the police. If Rons father had told the sheriff the truththat he was driving his own car and that they were a family on vacationthe sheriff wouldnt have believed him. He would have assumed the car was stolen. In the event that the sheriff did believe it was Rons fathers car, the rage and jealousy he might have felt at the thought of a black man owning a nicer car than a police officer might have triggered a beating, torture, or even murder. From that day on, Ron noticed these hats strategically placed, like unarmed weapons, in the back seat of nearly every black mans car.

..........

Standing in the kitchen between the sage-speckled countertop and the wall-mounted oven, I listened to Rons story, stone-faced. Everybody had one, he said, referring to the chauffeurs cap. And you always kept it in the car. And then, without any provocation, other stories about his days growing up in Tennessee tumbled out. Ron talked about his cousin slipping out of town in the middle of the night because the Ku Klux Klan was set to lynch him. I listened with a knot in my stomach, trying to swallow my rage and sadness before tears filled my eyes. I didnt want my emotions to distract him from telling his story.

Ron Burford was my stepfather. I had known this man for more than thirty years, but this was the first time he had told me anything about the pain of growing up in the Jim Crow South. And its not that he was a quiet man; Ron loved to talk. He could talk for hours. My mom and my sister and I would try to scoot out of the kitchen before he started in on another one of his long Southern yarns, ones that we had heard before. But it wasnt until I started this project that he shared these stories with me. It was only then, at the age of forty-six, that I realized I had earned his trust. This was a huge accomplishment, because after what he and most black men of his generation had lived through in this country, he felt he couldnt trust anyone.

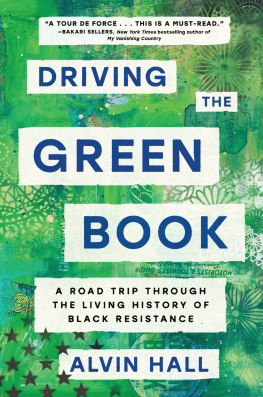

I think Ron started to trust me around 2014, soon after I called home asking about the Green Book. I had just seen a copy of it for the first time, tucked away under glass at the Autry Museum of the American West, in Los Angeles. It was a travel guide that was published for black people during the Jim Crow era. Id never known such a thing existed. Right after leaving the Autry, I called my parents in Columbus, Ohio, and asked Ron if he had ever used the Green Book. He said, Im not sure; probably. There were a few black guides back then.

He was right. There were about a dozen other black travel guides, but the Green Book was in print for the longest period of time and had the widest readership. Victor Hugo Green, a man with a seventh-grade education, published the first Green Book, in Harlem in 1936, and he worked on it until his death in 1960. His wife, Alma, took up the mantle and kept the Green Book going until 1962. In 1965, Langley Waller, an engraver and former writer for Harlems newspaper the