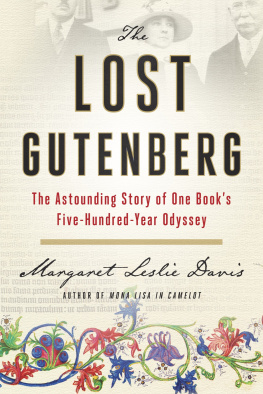

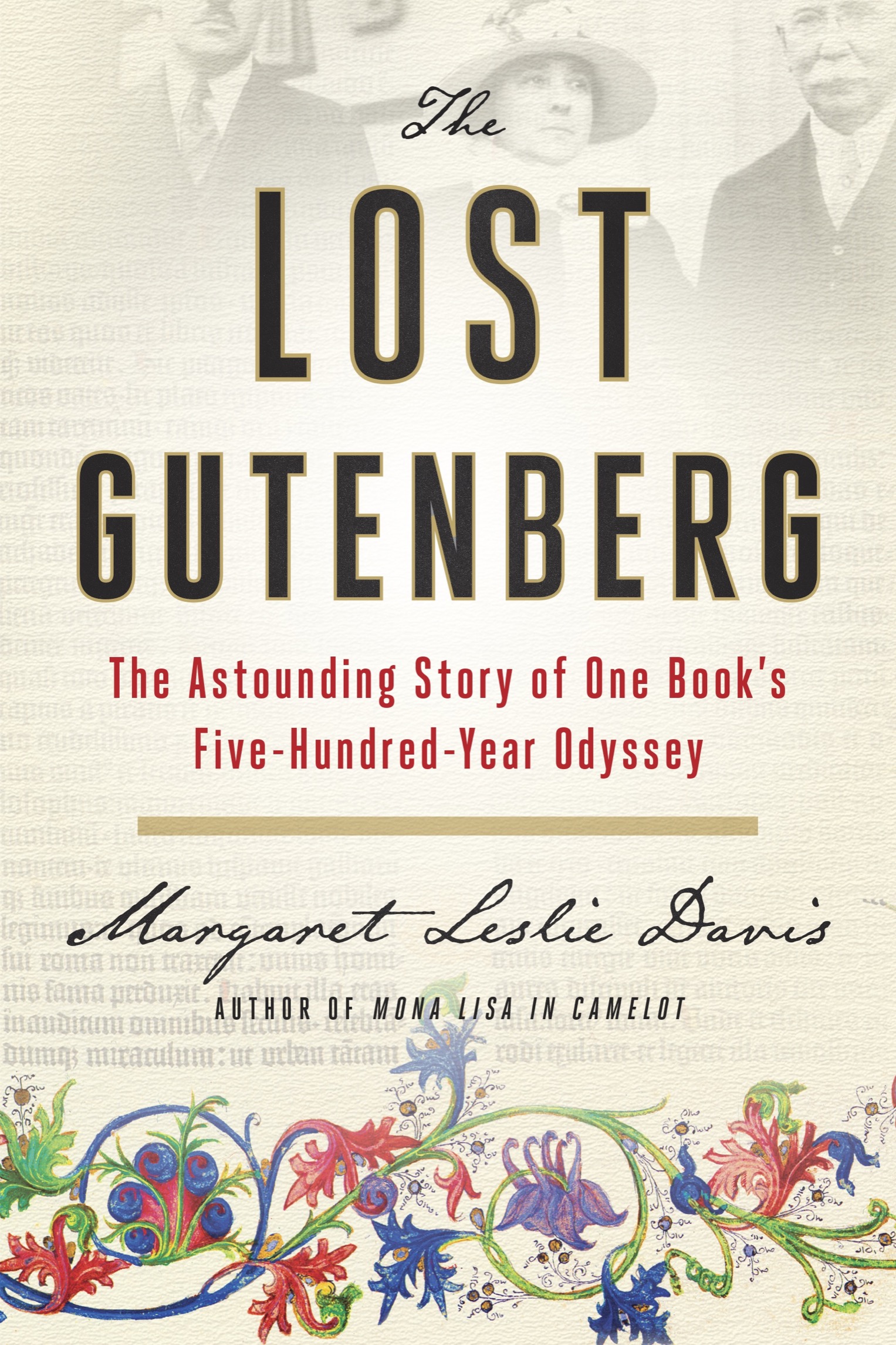

The Gutenberg Bible is a masterpiece of world culture. Only forty-eight or forty-nine copies of this landmark work survive, and of those, only one has been owned by a woman collector. This is the true story of that book, the copy designated as Number 45, printed by Johann Gutenberg sometime before August 15, 1456.

CHAPTER ONE

Million-Dollar Bookshelf

A WO ODEN BOX CONTAINING one of the most valuable books in the world arrives in Los Angeles on October 14, 1950, with little more fanfareor se curitythan a Sears catalog. Code-named the commode, it was flown from London via regular parcel post, and while it is being delivered locally by Tice and Lynch, a high-end customs broker and shipping company, its agents have no idea what they are carrying and take no special precautions.

The widow of one of the wealthiest men in America, Estelle Betzold Doheny, is among a handful of women who collect rare books, and she has amassed one of the most spectacular libraries in the West. Acquisition of the Gutenberg Bible, universally acknowledged as the most important of all printed books, will push her into the ranks of the greatest book collectors of the era. Its arrival is the culmination of a forty-year hunt, and she treasures the moment as much as the treasure.

Estelles pursuit of a Gutenberg began in 1911, when she was a wasp-waisted, dark-haired beauty, half of a firebrand couple reshaping the American West with a fortune built from oil. Now seventy-five, she is a soft, matronly figure with waves of gray hair. The auspicious occasion brings a flash of youth to her face, and she is all smiles. But she resists the impulse to rip into the box, leaving it untouched overnight so she can open it with appropriate ceremony the next day.

Estelle has invited one of her confidants, Robert Oliver Schad, the curator of rare books at the Henry E. Huntington Library, to see her purchase, and at noon he arrives with his wife, Frances, and their eighteen-year-old son, Jasper. Estelles secretary, Lucille Miller, escorts the family through the mansions Great Hall to the library, and with a sweep of her hand invites the group to sit at the oblong wood table in the center. The Book Room, as Estelle affectionately calls it, is finished in rich redwood and had been her husbands billiard parlor. Its walls had once featured paintings related to Edward Dohenys petroleum empire, murals commissioned by the onetime prospector who drilled some of the biggest gushers in the history of oil. Today the room is lined with custom-built shelves for Estelles beloved booksher own personal empire, worth as much as Edwards oil.

Her collection began almost as a lark, sparked by popular lists of books that everyone should own, but now contains nearly ten thousand exceedingly rare volumes available only to the fabulously wealthy and culturally ambitiousgilded illuminated manuscripts glowing with saints and mythical creatures; medieval encyclopedias; and the earliest examples of Western printing, 135 incunabulabooks printed before the year 1501. Such seminal works of Western culture as Ciceros De officiis and Saint Thomas Aquinass Summa Theologica rub shoulders with a sumptuous 1477 copy of The Canterbury Tales. This is the million-dollar company the Gutenberg Bible will keep on its shelf.

The two-by-three-foot crate waits at the center of the table, spotlighted by a bronze-and-glass billiard lamp. When Estelle enters the room, accompanied by her companion and nurse, Rose Kelly, the group stands silent. Lucille takes out a pair of scissors and passes it around. Estelle, dressed for the occasion in a pale blue printed silk dress, a gem-studded comb at her right temple, wants everyone to take part, so each person makes a cut in the knotted cord that winds the package.

Its an emotional occasion for Lucille, too, a slim, long-limbed woman with center-parted, brown hair that curls up around her cheeks. Never without a pencil tucked behind her ear, she has a subdued beauty thats easy to miss, a pale, symmetrical face hidden behind her glasses. Lucille has been Estelles steady partner in the quest for the Gutenberg, party to every promise, hope, and near miss for nearly twenty years. She almost allows herself to smile as she pulls away the boxs coverings and lifts the lid, but then she sees the shabby mess inside. I could hardly believe my eyes, she said later. It just looked like a bundle of old tattered, torn papers. It was the most carelessly wrapped thing I ever saw.

It will be a miracle if the book is not damaged.

But as she lifts it out of the last of the wrappings, the Bible appears to be fine. For an expert like Robert Schad, there is no mistaking the original fifteenth-century binding of age-darkened brown calfskin stretched over heavy wood boards. The copy now in Estelle Dohenys possession is the first issue of the first edition of the first book printed with movable metal type, in near-pristine condition, its pages fresh and clean. The lozenge and floweret patterns stamped into the leather cover are still sharp and firm to the touch. Five raised metal bosses protect the covers, one ornament in the center and one set in an inch from each of the four corners. Two broken leather-edge clasps are the only reminders that this book, which has presented the Living Word for nearly five centuries, has been opened and closed often enough to wear down the heavy straps.