The Gutenberg Galaxy

The Gutenberg Galaxy

The Making of Typographic Man

MARSHALL McLUHAN

With new essays by W. Terrence Gordon, Elena Lamberti, and Dominique Scheffel-Dunand

First edition

University of Toronto Press Incorporated 1962

Reprinted 1966, 1967, 1968, 1980, 1986, 1988, 1992, 1995, 1997, 2000, 2002, 2006, 2008, 2010

This edition Estate of Corinne McLuhan 2011

New essays in this edition

University of Toronto Press 2011

Toronto Buffalo London

www.utppublishing.com

Printed in Canada

ISBN 978-1-4426-1269-3 (paper)

Translated into the following languages:

Catalan | Portuguese |

French | Polish |

German | Romanian |

Greek | Serbo-Croat |

Italian | Spanish |

Japanese | Swedish |

Printed on acid-free, 100% post-consumer recycled paper with vegetable-based inks.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

McLuhan, Marshall, 19111980

The Gutenberg galaxy : the making of typographic man / Marshall McLuhan ; with new essays by W. Terrence Gordon, Elena Lamberti and Dominique Scheffel-Dunand.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-4426-1269-3

1. Printing. 2. Communication and culture. 3. Technology and civilization. I. Title.

Z116.M15 2011 686.209 C2011-904384-X

University of Toronto Press acknowledges the financial assistance to its publishing program of the Canada Council for the Arts and the Ontario Arts Council.

University of Toronto Press acknowledges the financial support of the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund for its publishing activities.

Contents

W. TERRENCE GORDON

McLuhans Compass for the Voyage to a World of Electric Words

ELENA LAMBERTI

Not Just a Book on Media: Extending The Gutenberg Galaxy

DOMINIQUE SCHEFFEL-DUNAND

The Invisible and the Visible: Intertwining Figure and Ground in The Gutenberg Galaxy

McLuhans Compass for the Voyage to a World of Electric Words

W. TERRENCE GORDON

In a letter written to his in-laws on Christmas Day 1960, Marshall McLuhan mentioned that he had drafted a book in less than a month. Of all his publications, The Gutenberg Galaxy (henceforth GG), so explosive on the page, had the tidiest beginnings. The manuscript flowed from McLuhans pen until he had written 399 pages. There he stopped, so that the total of the carefully numbered foolscap sheets would be divisible by three. (As a symbol of intellectual and spiritual order, the number three retained great importance for him throughout his life.)

The books true beginnings go back at least to McLuhans teaching days at St Louis University in the 1930s and 40s, when he discussed ideas concerning the print him an eighteen-point outline of the work, pitching it as the icon smashing groundwork for an overhaul of undergraduate education.

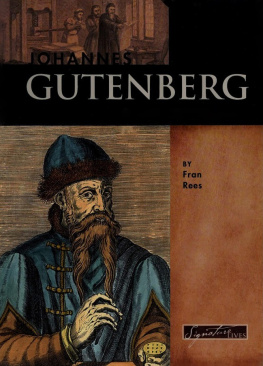

Today, a half-century after GG first appeared in print, the proliferation of electronic media has inevitably dwarfed the scope of the commentary that McLuhan wrote when television and computers were still in their infancy, but the passage of time has not diminished the iconoclastic force of the book. (Nor has that proliferation diminished the need for an overhaul of undergraduate education.) It is best read not simply as a harbinger of a post-literate society that would bewilder Johannes Gutenberg and that McLuhan himself would be shocked to find so entrenched so early in the twenty-first century, but as an enduring challenge to understand its subversive purpose.

Though many commentators radically misread McLuhan as intending to hasten the collapse of book culture, in fact he issued a call for shoring it up: Far from wishing to belittle the Gutenberg mechanical culture, it seems to me that we must now work very hard to retain its achieved values. need not be closed, provided we ask if the gifts spilling from it may impoverish us.

The cover of GG, perhaps promising by its title to be a science-fiction thriller, bore two upper-case Gs, set in huge a theme that is at the core of all his subsequent major works from Understanding Media to the posthumously published Laws of Media.

McLuhans contract for GG referred to it as The Gutenberg Era, a phrase found in its pages, but he settled on The Gutenberg Galaxy, not only for its alliterative value but to emphasize that a configuration of events had been spawned by the invention of the printing press. (Crucially, the second principal section of the book deals with the re configuration of Gutenbergs legacy and lays a foundation for examining events precipitated by the electronic galaxy and studying media in a framework still applicable today.) Galaxy allowed McLuhan to focus on media-induced events and to evoke his theme of effects as a cluster of environmental changes.

McLuhan cites a score of writers and thinkers in his opening pages, including historians of science, technology, and medicine. To these he will later add references to social and cultural historians, economists, and political later works and for reasons which he makes clear.

Wyndham Lewis, for example, had a new conception of what art is: Life with all the humbug of living taken out of it.

Though Lewis is quoted in GG only for his views on Italian antiquarianism, he had long since served McLuhan as a model for avoiding categorical judgments. McLuhans impetus towards the principles of integration and synthesis in all his work resonates with Lewiss ideal of reintegrating the arts of sculpture, painting, and architecture. In the first volume of the journal Blast, Lewis, as editor, had articulated the principle that the artist is not the slave of commotion but its master; McLuhan, the navigator of the electronic maelstrom that swamped the Gutenberg era, would teach the principle that understanding media provides the means of keeping them under control. Lewis understood the fragmenting effects of technology and spoke of them in terms that would be closely paralleled in McLuhans writings, beginning with GG. Lewiss concept of space contains the core of the idea that McLuhan would develop as the distinction between visual and acoustic space.

Like Lewis, McLuhan would move beyond his original aesthetic interests in the world of the arts to understanding the relationship between art and technology. McLuhan shared Lewiss concept of the artist being inextricably linked to the inevitable encroachments of technology. Both men accepted the necessity of facing the effects of technological advances as detached observers of their causes. Lewiss notion of the vortex as a mask of energy in relation to both art and technology was applied by McLuhan to language as both art and technology.

McLuhan knew Lewiss observation that the artist is always writing a history of the future because he alone is aware of the nature of the present, and he took this less as an article of faith than as a fact that could be demonstrated by citing and interpreting passages from Lewis, Joyce, Pound, Eliot, and others who showed their insights into the impact of new technologies. Such passages provided implicit programmatic statements for the educational reform at the heart of McLuhans vision. By contrast, shortcomings, inconsistencies, and errors of judgment were all too apparent to him in the works of analytical thinkers, including Harold Innis, to whom he nevertheless paid full homage.

Next page