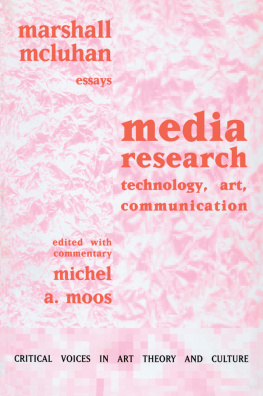

Marshall McLuhan

You Know Nothing of My Work!

DOUGLAS COUPLAND

ATLAS & CO. New York

Copyright 2010 by Douglas Coupland

The AQ Test appears courtesy of Simon Baron-Cohen and originally appeared in the 2001 Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders

Can the Internet Change Your Brain? by Nick Heath. Copyright 2010 CBS Interactive Limited. All rights reserved. ZDNET is a registered service mark of CBS Interactive Limited.

All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, scanning, or any information or storage retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

Atlas & Co. Publishers

15 West 26th Street, 2nd floor

New York, NY 10010

www.atlasandco.com

Distributed to the trade by W. W. Norton & Company

ISBN: 978-1-935-63318-1

CONTENTS

When you give people too much information, they instantly resort to pattern recognition to structure the experience. The work of the artist is to find patterns.

M.M.

is a numbing blow from which he never recovers.

M.M.

Marshall McLuhans online-generated Porn Star name

Pud Bendover

Marshall McLuhans online-generated Pimp name

Slick Tight

Marshall McLuhans online-generated Ho name

Skanka

Marshall McLuhans online-generated Prison Bitch name

Piglet

Marshall McLuhans online-generated Emo name

Abandoned by God

Marshall McLuhans online-generated Drag name

Vanilla Thunderstorm

Marshall McLuhans online-generated Pirate name

Jake the Well Tanned

Marshall McLuhans online-generated Mexican Wrestler name

Ratn Fuerte

Marshall McLuhans online-generated Goth name

Lord Fragrant Desiccated Corpse

Marshall McLuhans online-generated RPG name

Incomparable Brilliant Katana

Marshall McLuhans online-generated Outlaw Biker name

Ol Boozy Beefy Junkie MC

it may be the extension of consciousnesswill include television as its content, not as its environment, and will transform television into an art form. A computer as a research and communication instrument could enhance retrieval, obsolesce mass library organization, retrieve the individuals encyclopedic function and flip it into a private line to speedily tailored data of a saleable kind.

M.M.

1962

The Seer

The year is 1980 and it is spring. A man is lying on a couch in a cool, dark office in a quiet, suburban Tudor home. He is almost seventy years old. He is left-handed. He is heterosexual. He is in the city of Toronto, Ontario. He is staring at the ceiling. He is white. He is wearing a sweater over a button-down collared shirt. His name is Marshall. It is hard to know what is going through Marshalls mind because something has happened to him. He can no longer speak. He can no longer read. He can no longer write. This has been going on for half a year now, since he had his stroke. Oddly, he can perfectly understand what people are saying when they speak to himbut he cant generate words himself. And while he can also listen to the radio or watch TV, and understand what people there are saying, once the voices stop, the words in his head stop, too. What has happened to the voice inside his headis it dead? For that matter, is it even possible for ones inner voice to die? And if so, what would that silencing sound like? What can the sound of no voices be?

Marshall sees a bee trapped inside the room, batting itself on the windowpane. Tappa-tappa-bzzzt, tappa-tappa bzzzt He stands up and rescues the bee, and as he does so, he says, boy-oh-boy-oh-boythe two words he has been left with after the previous autumns gross insult to his brain, the words he says when he agrees with something. The outside air smells of lawn clippings and pollen. In the distance a dog barks. Marshall turns around and looks at his room: books stacked higgledy-piggledy on most available flat surfaces, an almost cartoonishly don-like office. It is killing Marshall that he looks at his books and cant even generate the word book himself. He knows that these books and papers represent his life. And then, suddenly, something happens. A radio in another room in the house is playing a Protestant hymn and, although he has been a fervent Catholic for over forty-two years, he begins to belt out the hymns lyrics. But the hymn ends, and so does Marshalls singing. He is returned to his world of sound effects, and he again surveys his books, many of which are books he wrote, so he knows them by their shape and colour but not their titles. Life is cruel and life is humbling. Marshall knows that he was once considered one of the best talkers in the world. He knows that he once had ideas that changed the way people looked at the world and at life, but again, he has been reduced to sound effects. But Marshall also knows that he once punned like a god. He knows that he once ruled a kingdom of anagrams and double entendres, and that his lifes core themes revolved around how we communicate from person to person, from generation to generation, and from one century to the next. He knows hed seen the future of the future. He knows hed become world renowned and world reviled, and now he cant even say a proper goodbye and good luck to a goddamn bee.

Timesickness

Part of writing a biography involves asking why we should care about the subject. was published in 1997. During these years Marshall was largely a boutique intellect for a small group of people whose thought patterns mapped closely onto his ownacademics and people working in the outer fringes of media, professionally and academically.

But somewhere around 2003 the texture of daily life inside Western media-driven societies began to morph, and quickly, to the point where, a half-decade later, its now obvious to people who were around in the twentieth century that time not only seems to be moving more quickly, but is beginning to feel funny, too. Theres no more tolerance for waiting of any sort. We want all the facts and we want them now. To go without email for forty-eight hours can trigger a meltdown. You cant slow down, even once, ever, without becoming irrelevant. Music has become more important because music is a constant. School reunions are beside the point because we already know what our old classmates have done. Children often spend more time in dreamland and cyberspace than in real life. Time is speeding up even faster.

And then the economy collapsed in a weird way that felt like a hard-to-describe mix of Google, The New York Timess website, pop-up ads for Russian pornography websites, and psychic radiation emitted by all those people you see standing by the Loblaws produce section at 6:15 on a week-night, phoning home to see if spinach is a good idea. All this information and more has overtly, osmotically, or perhaps inadvertently damaged a collective sense of time that has been working well enough since the Industrial Revolution and the rise of the middle classes. This timesickness is probably what killed the economy, and God only knows what its up to next. Everywhere we look, people are making online linksto conspiracy, porn, and gossip sites; to medical data sites and genetics sites; to baseball sites and sites for Fiestaware collectors; to sites where they can access free movies and free TV, arrange hookups with old flames or taunt old enemiesand time has begun to erase the twentieth-century way of structuring ones day and locating ones sense of community. People are now doing their deepest thinking and making their most emotionally charged connections with people around the planet at all times of the day. Geography has become irrelevant. Our online phantom world has become the new