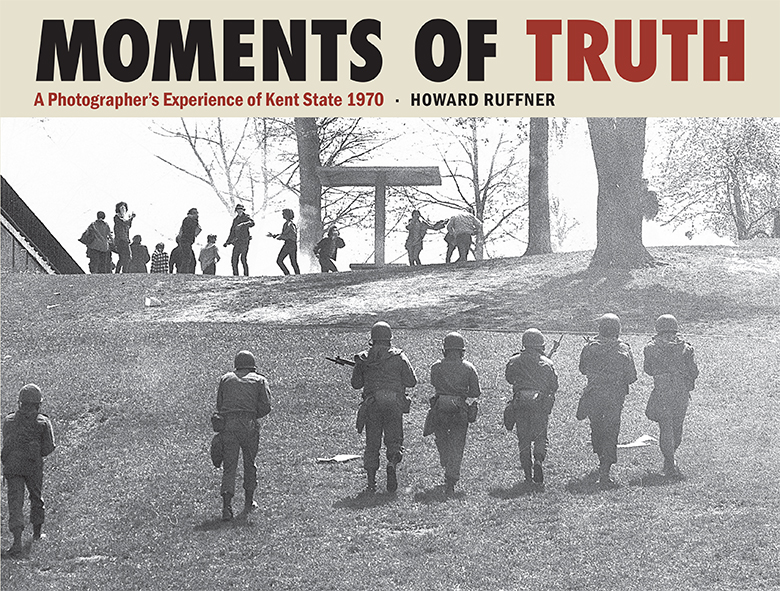

MOMENTS OF TRUTH

A Photographers Experience of Kent State 1970

Howard Ruffner

The Kent State University Press

Kent, Ohio

Frontis: Pictures capture the truth of the tragedy at Kent State on May 4, 1970.

2019 by Howard Ruffner

All rights reserved

Library of Congress Catalog Number 2019013587

ISBN 978-1-60635-367-7

Manufactured in Korea

No part of this book may be used or reproduced, in any manner whatsoever, without written permission from the Publisher, except in the case of short quotations in critical reviews or articles.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Ruffner, Howard, photographer, author.

Title: Moments of truth : a photographers experience of Kent State 1970 / Howard Ruffner.

Other titles: Photographers memoir of Kent State 1970

Description: Kent, Ohio : The Kent State University Press, [2019] | Includes index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019013587 | ISBN 9781606353677 (cloth)

Subjects: LCSH: Kent State Shootings, Kent, Ohio, 1970--Pictorial works. | Ruffner, Howard. | Kent State University--Students--Biography. | Photographers--United States--Biography. | Vietnam War, 1961-1975--Protest movements--United States--Pictorial works.

Classification: LCC LD4191.O72 R84 2019 | DDC 378.771/37--dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019013587

23 22 21 20 19 5 4 3 2 1

This book is dedicated to Allison, Jeffrey, Sandy, and William who were killed on May 4, 1970, on the campus of Kent State University during a peaceful protest rally, and to Dean, Joseph, John, Thomas, Alan, Douglas, James, Robert, and Donald who were wounded that same day by the unwarranted firing of weapons by the Ohio National Guard.

CONTENTS

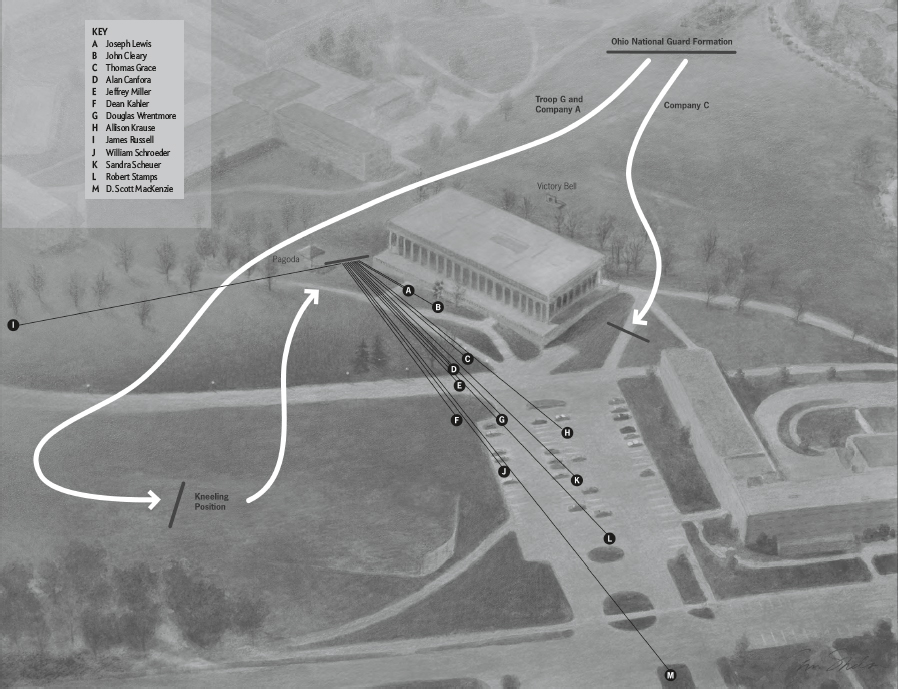

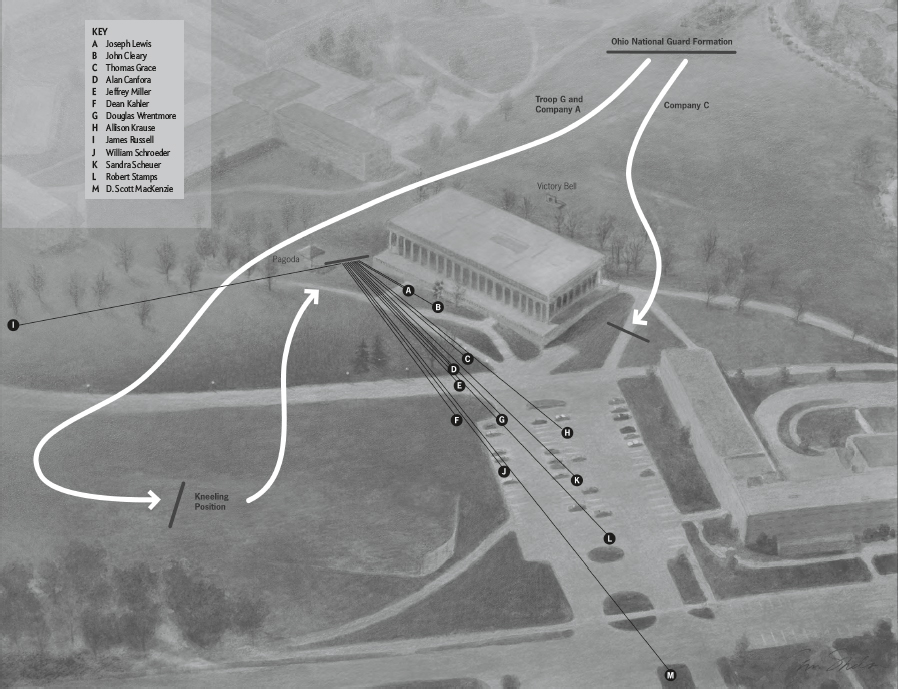

Site of the student rally and shootings on May 4, 1970. Curved lines trace the path of Ohio National Guard troops beginning at 12:05 P.M. on May 4, 1970. At 12:24, guardsmen turned 135 degrees at the Pagoda and 28 fired, primarily toward students in the Prentice Hall parking lot. Map by Chris Sheban with David Middleton. Copyright Kent State University. Reprinted with permission.

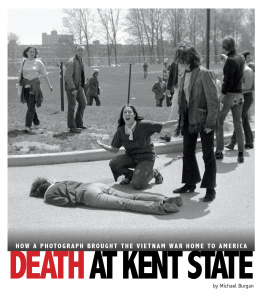

Fifty years ago, breaking news was deliverednot by Twitter or the Internet but by photojournalists whose work became the iconic images of our day or the first draft of history, a phrase attributed to US journalist Alan Barth. Such images abounded during the tumultuous and violent decade of the 1960s and were seared into the memory of a generation: a young JFK Jr. saluting his fathers coffin, a tear rolling down the cheek of MLK Jr.s widow, the twisted bodies of Vietnamese women and children in a ditch near My Lai.

On May 4, 1970, Howard Ruffner, a student who was stringing for Life magazinethe most important news-photo weekly of the timetook a picture that stunned the nation: a young Kent State University student named John Cleary lying in agony on the grass of his own campus, after being shot by Ohio National Guardsmen. Days before, the governor had sent armed troops to Kent State to quell sometimes fierce antiwar demonstrations.

At 24 years old, Howard Ruffner was relatively older than many of his fellow students and already an experienced newsman who had served in the US Air Force during Vietnam. As he points out at the conclusion of this fine memoir, richly illustrated with his own brilliant photographs, the images he captured forever bear witness to history and, like war, can never be erased from memory, either by those who participated, those who captured the images, or those who beheld them.

I was one of the thousands who played a part, albeit a minor one, in the demonstration at Kent that day, and was among the nine casualties who survived their wounds. Four others died, either instantly or within a short time. Although I fail to appear in any of Howard Ruffners pictures in this volumedespite being separated from the photographer at the time of the 67-shot salvo by a distance of no more than 50 feetRuffner did take a photograph of me or nearly did. In the Report of the Presidents Commission on Campus Unrest (1970), a Ruffner image shows a student looking down at me soon after I was hit in the left heel during the first moments of the Guardsmens 13-second barrage.

).

However, as a newsman, Howard Ruffner could not shun his duty to take such images, as distressful as they were to both victim and photographer, as he points out in this memoir. As is often forgotten, Ruffner was among the prey that day as well as the dead, the wounded, and the hundreds who escaped the barrage of bullets. Like all combat veterans, we share a common bond.

He writes about that day:

I heard screaming and yelling. I had a feeling of numbness that I still vividly recall. Several distraught female students approached me and told me to stop taking pictures. They felt I was invading everyones privacy. I knew I was intruding but told them I had to take pictures. I tried to push back my own feelings, even though I shared their disbelief and rage. I also knew I was on assignment and had to take these pictures to show the impact of this horror on innocent students.

Eight years later, I recall Ruffner when we crossed paths for the first time on a cold winter day in December 1978 at the federal building in downtown Cleveland. He was the first witness to take the stand for the plaintiffs, and I was about to take the stand as the second in a civil suit against Ohio governor James Rhodes and the Guardsmen who had shot at us. Ruffner had just rendered the opening testimony on behalf of all 13 shooting victims and their families.

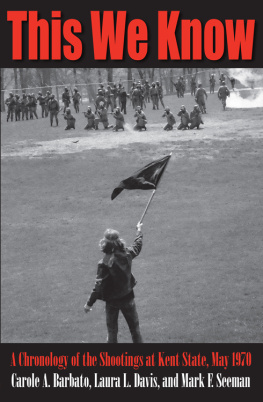

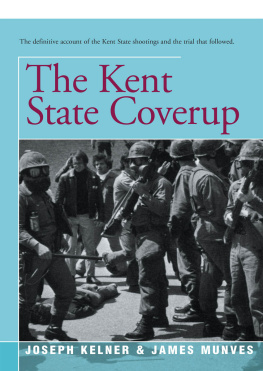

With a steely yet unobtrusive presencecomposure he describes in this memoir as both deliberate and gut-wrenchingly difficult to maintainhe painstakingly went through an extensive array of trial exhibit photographs that he and others had taken. Ruffner had done so effectively once before, in May 1975, having been the first witness selected by the plaintiffs lead counsel to testify in an earlier trial. Attorney Joe Kelner would later write of Ruffner that the students many images served as the most complete photographic record of the days deadly turn. Further, Kelner observed that Ruffner had the quiet manner of a mature person who weighed his words carefully.

Despite the collective efforts and the evidence presented, the 16-week trial, conducted from late May to late August 1975, ended in a bitter defeat for the plaintiffs. In that first court case, 9 of 12 jurors exonerated the governor and all of the Guardsmen who shot to death unarmed students at distances of between 270 and 390 feet. However, due to judicial mishandling of a threat made against a juror in the 1975 trial, a three-judge federal appeals court granted a new trial. Owing to Howard Ruffners personal authority and command of the body of work captured by his camera, he would once again spend days on the witness stand telling the story of what his photographs revealed. Indeed, he was the only non-plaintiff to provide testimony at both trials, the second of which resulted in an out-of-court settlement.

Repeatedly interrupted by defense counsel objections during the first trial, Howard Ruffner now has the opportunity, in these pages, to tell the unbroken story of a day that nearly broke America. He has done so, he relates in these pages, because even after almost 50 years, he is still haunted by the 1975 verdict. And, more to the point of his lifes work, how the power of photography, and the truth it conveys, somehow failed to convince the jury. Every photo is more than its surface, he writes. Each tells a story. The more I stare [at a photo], the more I see the truth. Despite that, he adds: Blood was spilled that day and has never been washed away.