BEHOLDING

BEHOLDING

SITUATED ART AND THE AESTHETICS OF RECEPTION

Ken Wilder

BLOOMSBURY VISUAL ARTS

Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

50 Bedford Square, London, WC1B 3DP, UK

1385 Broadway, New York, NY 10018, USA

BLOOMSBURY, BLOOMSBURY VISUAL ARTS and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

First published in Great Britain 2020

Ken Wilder, 2020

Ken Wilder has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as Author of this work.

For legal purposes the constitute an extension of this copyright page.

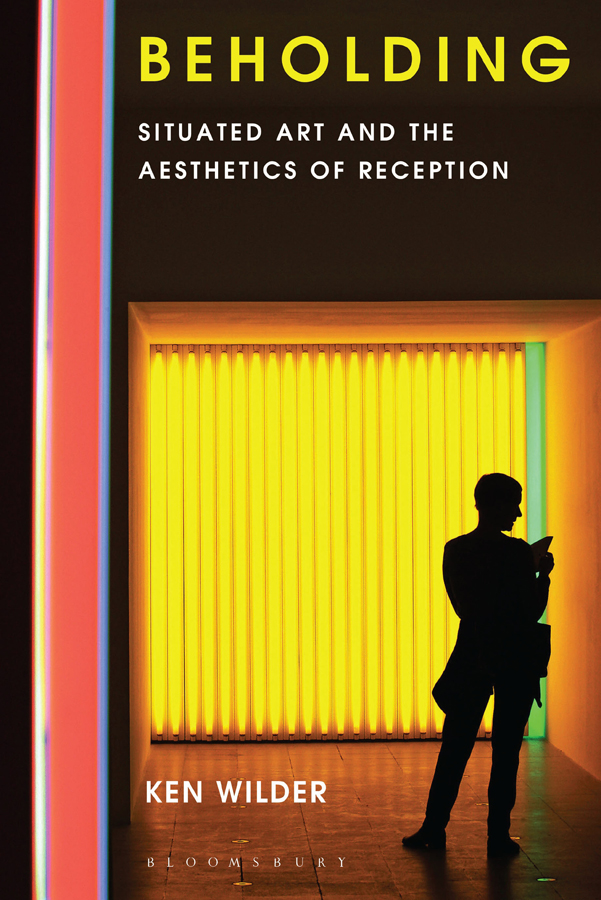

Cover design: Louise Dugdale

Cover image ADRIAN DENNIS/AFP via Getty Images

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers.

Bloomsbury Publishing Plc does not have any control over, or responsibility for, any third-party websites referred to or in this book. All internet addresses given in this book were correct at the time of going to press. The author and publisher regret any inconvenience caused if addresses have changed or sites have ceased to exist, but can accept no responsibility for any such changes.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress.

ISBN: HB: 978-1-3500-8840-5

ePDF: 978-1-3500-8842-9

ePub: 978-1-3500-8841-2

To find out more about our authors and books visit www.bloomsbury.com and sign up for our newsletters.

To Sharon

&

the memory of my parents

CONTENTS

This book proposes a theory of beholding art. More particularly, it proposes a theory of beholding situated art. While perhaps unfamiliar to some, I use this qualifying term to encompass not only rare examples of site-specific practice (a term subject to frequent misuse) but also group portraiture, painted for anticipated locations, and what we might call site-responsive art works that, while subject to different iterations, engage their situation as an essential part of the encounter. These are artworks that are sensitive to their site and anticipated audience and, while not necessarily in situ in a strong sense, are purposively sited within specific contexts, drawing aspects of that situation not only spatial but also institutional into the remit of the encounter.

Now, this might be thought of as being rather too heterogeneous a category of art practice to have any kind of critical purchase; indeed, even so-called autonomous artworks in traditional media such as painting and sculpture are affected by extrinsic factors: that is, the works outer apparatus, such as its frame or pedestal. Not only is an artworks conditions of access a factor to be taken into account, such as the ubiquitous white cube gallery, but our experience of the artwork is also altered by variants such as the position where it is hung on the wall or placed within the room, the quality of lighting, the materiality and colour of the surface on which it is hung or placed, its proximity to other works and so forth. Moreover, the juxtaposition with other similar and/or contrasting works perhaps as part of a series by the same artist, or the gathering of artworks under a curatorial theme will also affect our experience and understanding. In other words, extra-pictorial or extra-sculptural factors can profoundly affect how we perceive and interact with autonomous works of art, and in this sense all art is thus situated.

These curatorial factors are not, however, the subject of the book. Rather, I impose a caveat on the works to be considered in this volume, which delimits the concern to a distinct category of art practice. My subject is works where the experience of the situation is itself constitutive of the works meaning. Here the content of the work of art, to use the language of Susan Sontag, does not exist independently of the situation, and of the experience of that situation. A painting being placed too near the corner of a room, or at an awkward height, while affecting our experience at some level, is not, in and of itself, a contributory factor to the works semantic content. There are, however, artworks that might be said to imply a representational excess, used in a non-mimetic sense, in that the virtual space of the work extends to encompass the actual space of the beholder. Such works have an excess over and above that which is, strictly speaking, represented an excess of meaning that must be enacted or performed by the contributory presence of the beholder and is thus dependent upon perceptual, ideational and imaginative processes the spatially situated encounter prompts. Here, to remove a work from its original context will, indeed, change its meaning.

My primary concern is therefore with what John Shearman terms transitive works of art (which he opposes to self-sufficient intransitive works) that are only completed by the presence of the beholder, such that her performative role is necessary for realizing this representational excess. This conceives of beholding as a process, such that the resulting interaction constitutes an effect to be experienced rather than an object to be defined. But with such a caveat, have I not moved from a very broad category of art to, seemingly, an extremely narrow category? Perhaps so. Nonetheless, and not insignificantly, this group of works includes some of the most prominent artworks within the history of art. This is perhaps indicative that something significant is going on here. Indeed, that we are so often drawn to such works suggests that while they often deliberately problematize the beholder position, in bringing our orientation into play (while eluding our grasp) we find such works deeply engaging not least because we have work to do to complete the incomplete .

A key contention underpinning the book is that such situated works therefore perform a locative function, in terms of providing indexical cues as to the position the beholder must adopt in order to place herself in the requisite experiential connection to the works meaning. As such, they facilitate demonstrative or, more generally, indexical thought with respect to the virtual realm of the artwork (this, that, here, there, in front of, behind and so forth), which in situated works is indexed relative to the position we occupy in actual space. The artwork thus functions as though is not reducible to a form of indexical sign characterized by its positional mode of operation. It is my contention that this involves the imagination. More specifically (though my general argument is not dependent upon such an assertion), I believe such artworks utilize the demonstrative potential of mental imagery: where quasi-perceptual experiences inherit their apparent spatiality from binding processes used by the apparatus of early vision. In other words, this is an indexing that exploits a frame of reference shared with not only visual perception but also (given the bodys capacity to coordinate multiple frames of reference) other non-visual forms of spatial orientation. Unfortunately, given the limited space I am not in a position to defend such a claim; nonetheless, it is at least consistent with the position advanced by the cognitive scientist Zenon Pylyshyn. Moreover, it is deeply sympathetic to the embodied perception of Merleau-Ponty and James J. Gibson. Crucially, the contention that need concern us here is that situated artworks utilize concurrently perceived spatial cues from our actual environment (whether visual or otherwise) to locate ourselves relative to the artworks particular mode of virtuality, such that aspects of our actual situation are drawn into the works imaginative remit. Even in the case of situated painting, where we tend to be confined (though not always) to a particular viewpoint, this binds virtual space to our own bodily frame of reference, with all the implications of an embodied perception actively enmeshed in the world.

Next page