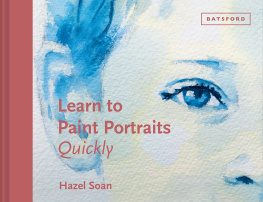

Robert Campin, Portrait of a Fat Man (Robert de Masmines), 142530.

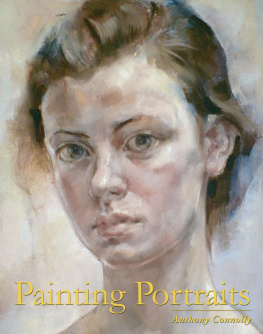

In Europe, recognizably individual portraits date back to the early fifteenth century (although they were possibly not described as portraits until the sixteenth century). Robert Campins Portrait of a Fat Man (Robert de Masmines), 142530, is an example of the closely observed likeness that still characterizes much contemporary portraiture. There is no attempt to idealize; Robert de Masmines has a fleshy, unbecoming gaze.

Fayum mummy portrait, Woman With a Double Strand of Pearls.

The early fifteenth century seems to have been an historical period during which an intensity of looking and recording became necessary or desirable. Prior to this, only Roman portrait busts aspire to the same degree of reality. There are times, perhaps, when our individuality, our uniqueness, has to be set or recorded. It is unlikely, however, that the function of a painted portrait in fifteenth-century Flanders would be the same as the function of a painted likeness today. Beliefs, values, technologies , our understanding of what it is to be human, have all changed since 1430.

It is conceivable that a painted representation in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries was used in the way a photograph might be used today, as a communication of appearance. In 1538 an English ambassador in Brussels arranged for Hans Holbein the Younger to paint Christina of Denmark. Henry VIII wanted to see the Duchesss likeness because he was thinking of marriage. She eventually married elsewhere, but Henry was much taken, it seems, with the sixteen-year-old depicted in Holbein s painting. Indeed, her likeness still captivates; the painting now hangs in the National Gallery in London. Nowadays, we have more immediate, technological means of communicating appearance, although similar transactions are probably just as risk-laden.

In 1956, the then leader of the Soviet Union, Nikita Khrushchev, attacked the cult of the individual and specifically the cult of Stalin. Khrushchev argued that this cult brought about rude violation of Party democracy, sterile administration, deviations of all sorts, cover-ups of shortcomings, and vanishings of reality. More recently, the cult of the individual has had other, more venal, manifestations and cult status has become rather more easy to acquire. I have certainly heard a thirteen-year -old refer to an acquaintance as a legend. The prospect of becoming famous has elbowed its way up in the collective psyche from being a consequence of achievement to being a career aspiration in itself, fuelled by reality television. Celebrity even has its own professional hierarchy C listers and B listers, all hoping one day to be A listers. Fame has been democratized, as was foretold by the shaman, Andy Warhol. It has to be self-evident that we have all scratched away at reality a little by becoming complicit in this cult of the individual. The Co- operative Funeral Service recently conducted a survey of music played at funerals. Frank Sinatras rendering of My Way was the song most frequently requested to mark a persons passing. This might be trivializing the point, but portraiture must owe something to our continuing, our rampant, fascination with the individual; with ourselves as celebrities.

Nevertheless, since the Renaissance the portrait has undoubtedly become something of a mark of status, a fitting tribute to a remarkable individual. The great and the good, the celebrated and the infamous, have all gone under the brush. Ironically, the very great are rarely the subject of very great portraits. The subjects of those truly unforgettable paintings, such as the portrait of Baldassare Castiglione by Raphael, are often rather minor historical figures. Even those who were kings, like Philip IV of Spain, are arguably more easily remembered today because they were painted by such painters as Velzquez. Another example, Madame Moitessier, may well have done it her way, but we think of her now because her husband, a wealthy banker, had the means and judgment to commission Ingres to paint her portrait. When we call to mind the painting of Lord Ribblesdale, we remember John Singer Sargent, just as in the crematorium it is difficult not to think of Frank Sinatra.