This book made available by the Internet Archive.

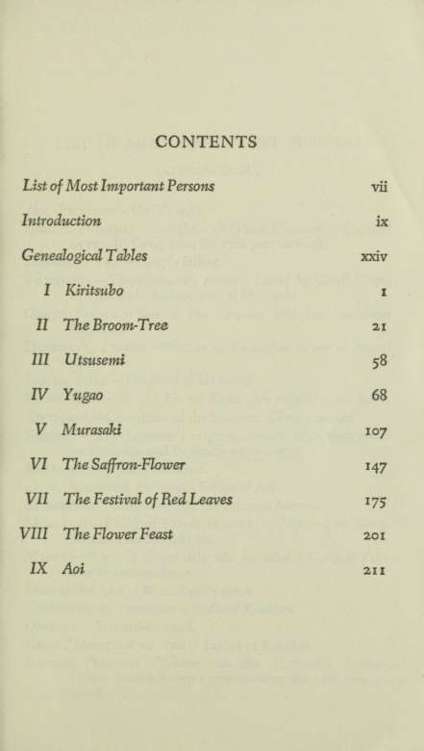

LIST OF MOST IMPORTANT PERSONS (alphabetical)

Aoi, Princess Genji's wife.

AsAGAO, Princess Daughter of Prince Momozono. Courted

in vain by Genji from his 17th year onward. Emperor, The Genji's father.

FujiTSUBO The Emperor's consort. Loved by Genji. Sister of Prince Hyobukyo; aunt of Murasaki.

Genji, Prince Son of the Emperor and his concubine Kiritsubo.

Hyobukyo, Prince Brother of Fujitsubo; father of Murasaki.

Iyo no Suke Husband of Utsusemi.

Ki NO ICami Son of Iyo no Kami, also called Iyo no Suke.

Kiritsubo Concubine of the Emperor; Genji's mother,

KoKiDEN The Emperor's original consort; later supplanted by Kiritsubo and Fujitsubo successively.

KoREMiTSu Genji's retainer.

Left, Minister of the Father of Aoi.

M0M020N0, Prince Father of Princess Asagao.

Murasaki Child of Prince Hyobukyo. Adopted by Genji. Becomes his second wife.

Myobu A young Court lady who introduces Genji to Princess Suyetsumuhana.

NoKiBA NO Ogi Ki no Kami's sister.

Oborozukiyo, Princess Sister of Kokiden.

Omyobu Fujitsubo's maid.

Right, Minister of the Father of Kokiden.

RoKujo, Princess Widow of the Emperor's brother. Prince Zembo. Genji's mistress from his 17th year onward.

viii LIST OF MOST IMPORTANT PERSONS

Shonagon Murasaki^s nurse.

SuYETSUMUHANA, Princess Daughter of Prince Hitachi.

A timid and eccentric lady. To NO Chu JO Genji's brother-in-law and great friend. Ukon Yugao's maid.

Utsusemi Wife of the provincial governor, lyo no Suke. CxDurted by Genji.

YuGAo Mistress first of To no Chujo then of Genji. Dies bewitched.

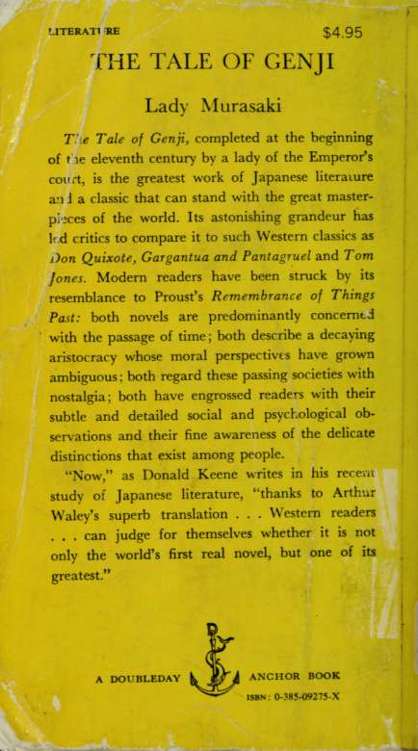

INTRODUCTION

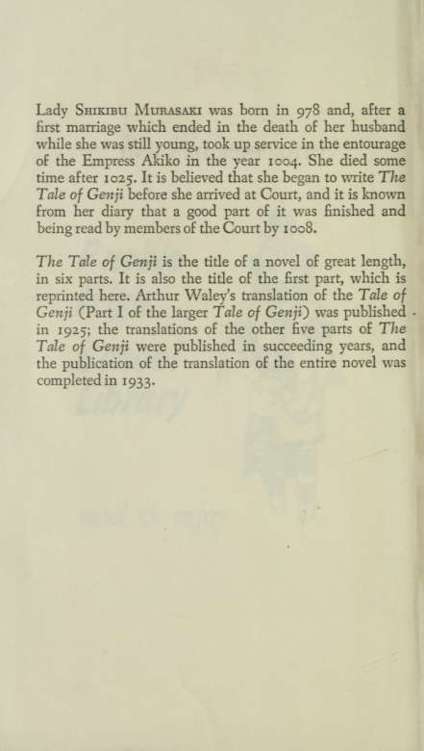

MuRASAKi Shikibu was bom about a.d. 978. Her father, Tametoki, belonged to a minor branch of the powerful Fujiwara clan. After holding various appointments in the Capital he became Governor first of Echizen (probably in 1004); then of a more northerly province, Echigo. In 1016 he retired and took his vows as a Buddhist priest.

Of her childhood Murasald tells us the following anecdote:^ When my brother Nobunori^ (the one who is now in the Board of Rites) was a boy my father was very anxious to make a good Chinese scholar of him, and often came himself to hear Nobunori read his lessons. On these occasions I was always present, and so quick was I at picking up the language that I was soon able to prompt my brother whenever he got stuck. At this my father used to sigh and say to me: 'If only you were a boy how proud and happy I should be.** But it was not long before I repented of having thus distinguished myself; for person after person assured me that even boys generally become very unpopular if it is discovered that they are fond of their books. For a girl, of course, it would be even worse; and after this I was careful to conceal the fact that I could write a single Chinese character. This meant that I got very little practice; with the result that to this day I am shockingly clumsy with my brush.'

Betw^een 994 and 998 Murasald married her kinsman Fujiwara no Nobutaka, a lieutenant in the Imperial Guard. By him she had two daughters, one of w^hom married the Lord Lieutenant of Tsukushi and is reputed

^ Diary, Hakubunkwan text, p. 51.

2 Died young, perhaps about 1012, while serving on his father's staff in Echigo.

(very doubtfully) to be the authoress of an uninteresting novel, the Tale of Sagorovw. Nobutaka died in looi, and it was probably three years later that Murasaki's father was promised the governorship of Echizen. Owing to the machinations of an enemy the appointment was, at the last minute, almost given to someone else. Tametoki appealed to his kinsman the Prime Minister Fujiwara no Michinaga, and was eventually nominated for the post*

Murasaki was now about tw^enty-six. To have taken her to Echizen would have ended all hope of a respectable second marriage. Instead Tametoki arranged that she should enter the service of Michinaga's daughter, the very serious-minded Empress Akiko, then a girl of about sixteen. Part of Murasaki's time was henceforth spent at the Emperor's Palace. But, as was customar\^, Akiko frequently returned for considerable periods to her father's house. Of her young mistress Murasaki writes as follows:* *The Empress, as is well known to those about her, is strongly opposed to anything savouring of flirtation; indeed, when there are men about, it is as well for anyone who wants to keep on good terms with her not to show herself outside her own room.... I can well imagine that some of our senior ladies, with their air of almost ecclesiastical severit}^, must make a rather forbidding impression upon the world at large. In dress and matters of that kind we certainly cut a wretched figure, for it is w^ell known that to show the slightest sign of caring for such things ranks wdth our mistress as an unpardonable fault. But I can see no reason why, even in a society where young girls are expected to keep their heads and behave sensibly, appearances should be neglected to the point of comicality; and I cannot help thinking that Her Majesty's outlook is far too narrow and uncompromising. But it is easy enough to see how this state of affairs arose. Her Majesty's mind was, at the time when she first came to Court, so entirely innocent and her ov^m conduct so completely impeccable that, quite apart from the extreme reser\^e which is natural to her, she could never herself conceivably have

3 Diary, p. 51.

occasion to make even the most trifling confession. Consequently, whenever she heard one o us admit to some shght shortcoming, whether of conduct or character, she henceforward regarded this person as a monster of iniquity.

'True, at that period certain incidents occurred which proved that some of her attendants were, to say the least of it, not very well suited to occupy so responsible a position. But she would never have discovered this had not the offenders been incautious enough actually to boast in her hearing about their trivial irregularities. Being young and inexperienced she had no notion that such things were of everyday occurrence, brooded incessantly upon the wickedness of those about her, and finally consorted only with persons so staid that they could be relied upon not to cause her a moment's anxiety.

'Thus she has gathered round her a number of very worthy young ladies. They have the merit of sharing all her opinions, but seem in some curious way like children who have never grown up.

*As the years go by Her Majesty is beginning to acquire more experience of life, and no longer judges others by the same rigid standards as before; but meanwhile her Court has gained a reputation for extreme dulness, and is shunned by all who can manage to avoid it.

Next page