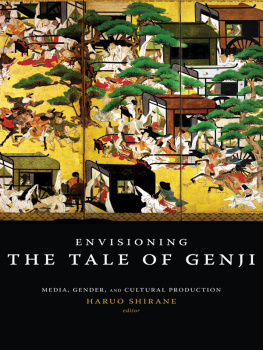

ENVISIONING

The Tale of Genji

Studio of Iwasa Matabei. Battle of the Carriages (detail). Mid-seventeenth-century six-panel folding screen, in ink, color, gold, and gold leaf on paper. 152.4 360.7 cm. John C. Weber Collection, New York City. Aois white-robed attendants push strenuously at the shafts to move Rokujs carriage off to the left. (PHOTO: JOHN BIGELOW TAYLOR)

ENVISIONING

The Tale of Genji

Media, Gender, and Cultural Production

EDITED BY

Haruo Shirane

Columbia

University

Press

New York

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2008 Columbia University Press

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-51346-3

Library of Congress Cata loging-in-Publication Data

Envisioning the Tale of Genji : media, gender, and cultural production / edited by Haruo Shirane.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-231-14236-6 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-231-14237-3 (pbk. : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-231-51346-3 (e-book)

1. Murasaki Shikibu, b. 978? Genji monogatari. 2. Murasaki Shikibu, b. 978?Influence. 3. Murasaki Shikibu, b. 978?Appreciation. 4. Arts, Japanese. 5. Arts and societyJapan. I. Shirane, Haruo, 1951 II. Title.

PL788.4.G43E58 2008

895.6314dc22

2007052280

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

Designed by Lisa Hamm

Contents

Envisioning The Tale of Genji: Media, Gender, and Cultural Production is about the profound impact that The Tale of Genji has had on Japanese culture for more than a thousand years. Much has been written about the remarkable narrative that Murasaki Shikibu composed in the early eleventh centuryits plot, its characters, its setting, its language, and its relation to earlier poetry and literaturebut little has been written about the equally remarkable influence that The Tale of Genji has had on Japanese culture, an impact greater than that of any other single work of Japanese literature. Today, both in and outside Japan, the Genji is synonymous with Japanese literature and culture.

The contributors to this book, experts in diverse fields, examine the complex relationship between The Tale of Genji as the pinnacle of high culture and The Tale of Genji as a phenomenon of popular culture, looking at it not only in the context of the commentary tradition, textbooks, and modern nation building, but also as the object of parody and pastiche and the subject of works in such diverse forms as illustrated books, ukiyo-e, theater, film, manga, and anime. Envisioning The Tale of Genji analyzes the roles of literary genre (poetry, fiction, commentary, modern novel), media (painting, n theater, ukiyo-e, printed book), and education in both the canonization and the popularization of the Genji, paying particular attention to the relationship between written text and visual culture, which played a major part in re-creating and re-envisioning of The Tale of Genji over the centuries.

This book also addresses gender in relation to cultural production. By the end of the medieval period, The Tale of Genji had come to be regarded as a major symbol of Heian court culture. Having been written by a woman mainly about women and for women, it became closely associated with the portrayal of aristocratic women in fiction, poetry, painting, and n. By the Edo period, the Genji had also become an integral but problematic part of womens education. The Tale of Genjis female authorship and depiction of amorous relationships, particularly Genjis illicit affair with Fujitsubo, the emperors chief consort and Genjis stepmother, made the tale a repeated target for harsh criticismfirst by Buddhist writers in the medieval period, then by Confucian scholars in the Edo period, and finally by critics in the Taish and prewar Shwa periods.

Envisioning The Tale of Genji takes up where Inventing the Classics: Modernity, National Identity, and Japanese Literature (Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, 2000), edited by Tomi Suzuki and me, leaves off. Inventing the Classics, which also was published in Japanese and Korean editions, is the first book to examine seriously the canonization of noted works of classical Japanese literature and their relationship to power, authority, and academic institutions. While examining a wide range of major textsfrom the Kojiki (Record of Ancient Matters) to The Tales of the Heike to the puppet plays of Chikamatsu Monzaemonthere was not enough room to address fully three related major issuesthe canonization of The Tale of Genji, the role of popular culture, and the re-creation and cannibalization of classical texts by a variety of mediathat lie at the heart of this book. For this reason, Inventing the Classics and Envisioning The Tale of Genji should be read together.

Envisioning The Tale of Genji had its origins in an international symposium, The Tale of Genji in Japan and the World: Social Imaginary, Media, and Cultural Production, held at Columbia University, New York, on March 2526, 2005. Organized by Melissa McCormick and me, the conference included twenty-one speakers and ten respondents from the United States, Canada, Australia, and Japan.

The symposium was funded by major grants from the Japan Foundation and Toshiba International Foundation, with support from Japan Airlines, the Donald Keene Center for Japanese Culture, the Departments of East Asian Languages and Cultures and of Art History and Archaeology at Columbia University, and John Weber, who sponsored the final dinner. To all we are most grateful.

Special thanks to the many participants for their insightful presentations, spirited discussion, and helpful feedback, especially Paul Anderer, Patrick Caddeau, Carol Cavanaugh, Thomas Harper, Ikeda Shinobu, Edward Kamens, Kawazoe Fusae, Komine Kazuaki, Matsuoka Shinpei, Julia Meech, Midorikawa Machiko, Mitamura Masako, Miyakawa Yko, Joshua Mostow, Richard Okada, Winnie Olsen, Gaye Rowley, Nakajima Takashi, Royall Tyler, Masako Watanabe, and Michael Watson. My gratitude to the doctoral students who assisted in the translations and at the conference: Michael Emmerich, Chelsea Foxwell, Satoko Naito, Gian Piero Persiani, Satoru Saito, Tomoko Sakomura, Saeko Shibayama, Mathew Thompson, and Anri Yasuda. I am eternally grateful to Lewis Cook for his detailed comments and advice.

At Columbia University Press, Irene Pavitt did a superb job as editor, and I thank Jennifer Crewe for her unstinting support and wise counsel.

I gratefully acknowledge the Kajima Foundation for the Arts and the Metropolitan Center for Far Eastern Art Studies for generous publication assistance. I also thank John Weber for the support for and permission to use his Genji painting for the cover and frontispiece.

This book is dedicated to the memory of Edward G. Seidensticker (19212007), who first taught me the joys of The Tale of Genji and provided me with much inspiration and friendship over the years.

ALL JAPANESE names are given in Japanese order, with family name first and personal name second, except for the Japanese contributors to this volume, whose names are given in English order.

The English translations of the Japanese chapter titles of The Tale of Genji are available at the back of this book.

Next page