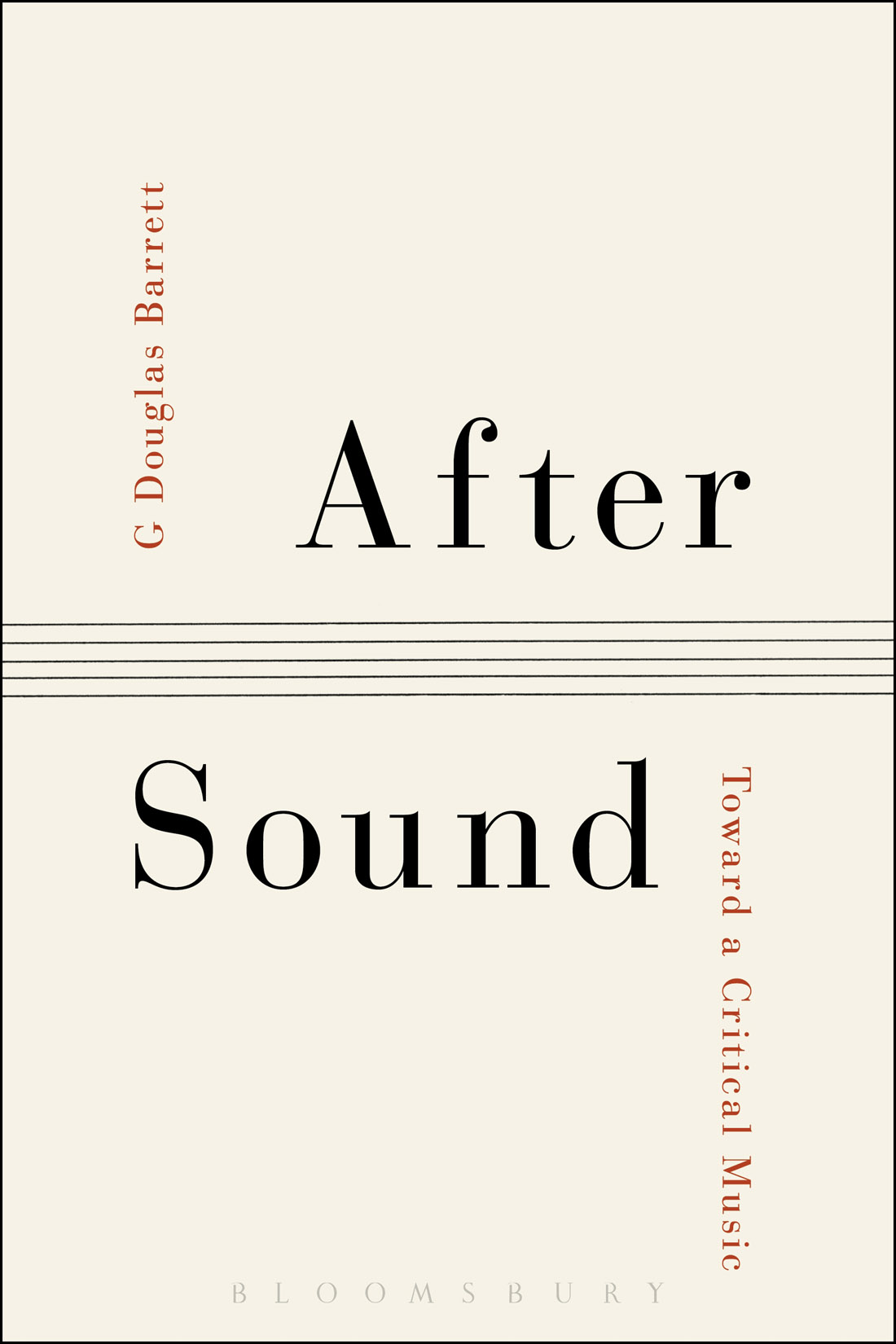

Barrett G. Douglas - After Sound

Here you can read online Barrett G. Douglas - After Sound full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. publisher: Bloomsbury USA, genre: Art. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:After Sound

- Author:

- Publisher:Bloomsbury USA

- Genre:

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

After Sound: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "After Sound" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

After Sound — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "After Sound" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

After Sound

After Sound

Toward a Critical Music

G Douglas Barrett

Bloomsbury Academic

An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Inc

Contents

Music After Sound

This book seeks to reimagine music as a critically engaged art form in dialogue with contemporary art, continental philosophy, and global politics. Represented by a diverse set of artists and musicians working during the past ten years, the artworks and analyses herein interrogate religion, gender, sexuality, HIV/AIDS, education, debt, finance, speculation, and labor. The discussions that follow will question received ideas about music and rework some of its basic tenets. Before proceeding, then, we must suspend the notion of music as a series of discrete sounds identifiable as tones, or notes with determinate pitches, etc., and which, taken together, compose what is commonly referred to as a musical work. For not only is the work-concept exemplified by the late-eighteenth-century musical score put into question, but here musical tones also remain optional. In fact, sound does not form the primary focus of the artistic practices pursued in this book. The first two chapters, for example, are dedicated to silence, the very absence of soundor, more precisely, the two rather different configurations of post-Cagean silence found in the experimental music collective Wandelweiser and contemporary art and AIDS activist group Ultra-red. But isnt music composed of sound?

One may object to the idea that silence can figure as a music without sound by arguing, for example, that John Cages 1952 composition refers to sound through its absence: by presenting the concert hall, the audience, and a musician who remains silent, sound is alluded to precisely by its withholding. Sound, in this argument, functions as the irreducible condition of music: music is seen as the aesthetic form that gives sound its proper seating. What happens, though, when sound is radically rescinded as the epistemological grounds upon which music is situated as an art form? What if music had never been a sound art in the first place?

It might come as a surprise, but the very notion of music as sound is a relatively recent invention. With its roots in the writings of a group of German thinkers in the early 1800s, the equating of music with instrumental sound

Absolute music, further sedimented in the mid-nineteenth-century musical aesthetics of Eduard Hanslickparticularly his notion of the specifically musical (as opposed to the extra-musical)would undergo its most exhaustive sequence in the music of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, expanding to include electronic sound and recording technologies among other formal and technological innovations. This music, which stretches from Beethoven to Boulez, but also includes Ruth Crawford Seeger, Pierre Schaeffer, and Karlheinz Stockhausen, worked through the same artistic modernism that brought us abstract expressionism and the subsequent debates around medium specificity in the visual arts. (It was the same artistic modernism because the birth of absolute music, as many would have it, was also the birth of artistic modernism.) Furthermore, language (including conceptuality, logos , etc.) has remained categorically excluded from music, thereby precluding such discursive forms.

How, then, can music become critical (in and of its own form)?

Whither Criticality?

Critical music turns on the question of language because for critical engagement of any kind, meaning is necessary. Language is distinct from meaning, but the two nonetheless rely on one another since language forms the substance and expression of meaning. Ideas leave traces, carve impressions into the world. Constituting a specific kind of matter(ing), concepts impose a consequential ) materialist conceptualism : the notion of a conceptual art that acknowledges the inherent discursivity of artistic practice while taking into account the material impact language and ideas have on the real. But does this mean that critical practice is possible today?

Considering the historical present, in which everything up to and including thought itself has proven commodifiable, is not the very notion of criticality a naive and outmoded concept? If critical art strives, in Chantal Mouffes words, to contribute to unsettling the dominant hegemony, works that appear simultaneously to contain thesis and antithesis. If the tension that arises through such a contradiction leads to a crack in the existing order, an opening onto a special kind of difference, then perhaps in such a case a critical practice might emerge.

As such, critical art is circumstantial, provisional, contextually dependent, and historically specific; it requires reflection and reflexivity, intention and enunciation. Critical in its content, writes Guy Debord in 1963, such art must also be critical of itself in its very form. And so to achieve this kind of engagement, musics concept as (nonlinguistic) sound requires revision. Or at least circumvention.

Sound Art?

Sound art, and its related discourses, represents one such attempt to circumvent the formal boundaries that have prevented this kind of a reorganization or transformation of music. As early as the 1960s, long after music had begun to conceive of itself as organized sound,

Following a recognition of this supposedly new paradigm, sound art faced a twofold legitimation crisis. First, sound art would need to provide a critique of music to legitimate its existence as a category. What could sound art offer that music, the existing art of sounds, could not? Theorists could, for example, criticize music as an essentially Greenbergian art form incapable of situating itself within the kind of expanded field first proposed by visual artfor example, in sculpture in the 1960s. Nearly a decade and a half after Rosalind Krausss inauguration of the postmedium condition (and almost a half-century since conceptual art began its critical interrogation of medium), sound art appears regressive, if not anachronistic.

Even from the outset, sound art had been complicated by the basic categorical difficulty of construing soundat once a phenomenon, material, and senseas an artistic medium. Would such a medium be limited to sound recordings, installations, sculptures, or objects that make sounds? Would it include performance, poetry, film, video, or even dance? Would Fluxus and Happenings be considered sound art? Considering similar questions, Max Neuhaus criticized sound arts taxonomical short circuit between material and medium by suggesting that in any other form the determination would appear ridiculous:

Its as if perfectly capable curators in the visual arts suddenly lose their equilibrium at the mention of the word sound. These same people who would all ridicule a new art form called, say, Steel Art which was composed of steel sculpture combined with steel guitar music along with anything else with steel in it, somehow have no trouble at all swallowing Sound Art.

Neuhauss critique of sound art appeared as a short text in the sound art exhibition Volume: Bed of Sound held in 2000 at MoMA PS1. As an artist often included in these kinds of exhibitions, Neuhauss site-specific installations and architectural interventions are cited by sound art theorists as forerunners of the genre. Yet despite his background as a musician and his variegated practice, Neuhauss works continue to be grouped around what the artist calls an unremarked commonality: sound.

In form, sound art parallels absolute music. Although sound art appeared over a century and a half later and lacked the metaphysical pretensions of absolute music, both movements sought to posit an essentially medium-specific art form based on sound. Absolute music and sound art point from different perspectives to the same construction: sound as an autonomous medium. This is not to reduce the category to what Seth Kim-Cohen calls sound art fundamentalism But more than an incidental categorical overlap, sound art and new music similarly reflect absolute musics primary determining feature: sound. Sound art is , essentially, absolute music.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «After Sound»

Look at similar books to After Sound. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book After Sound and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.