Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

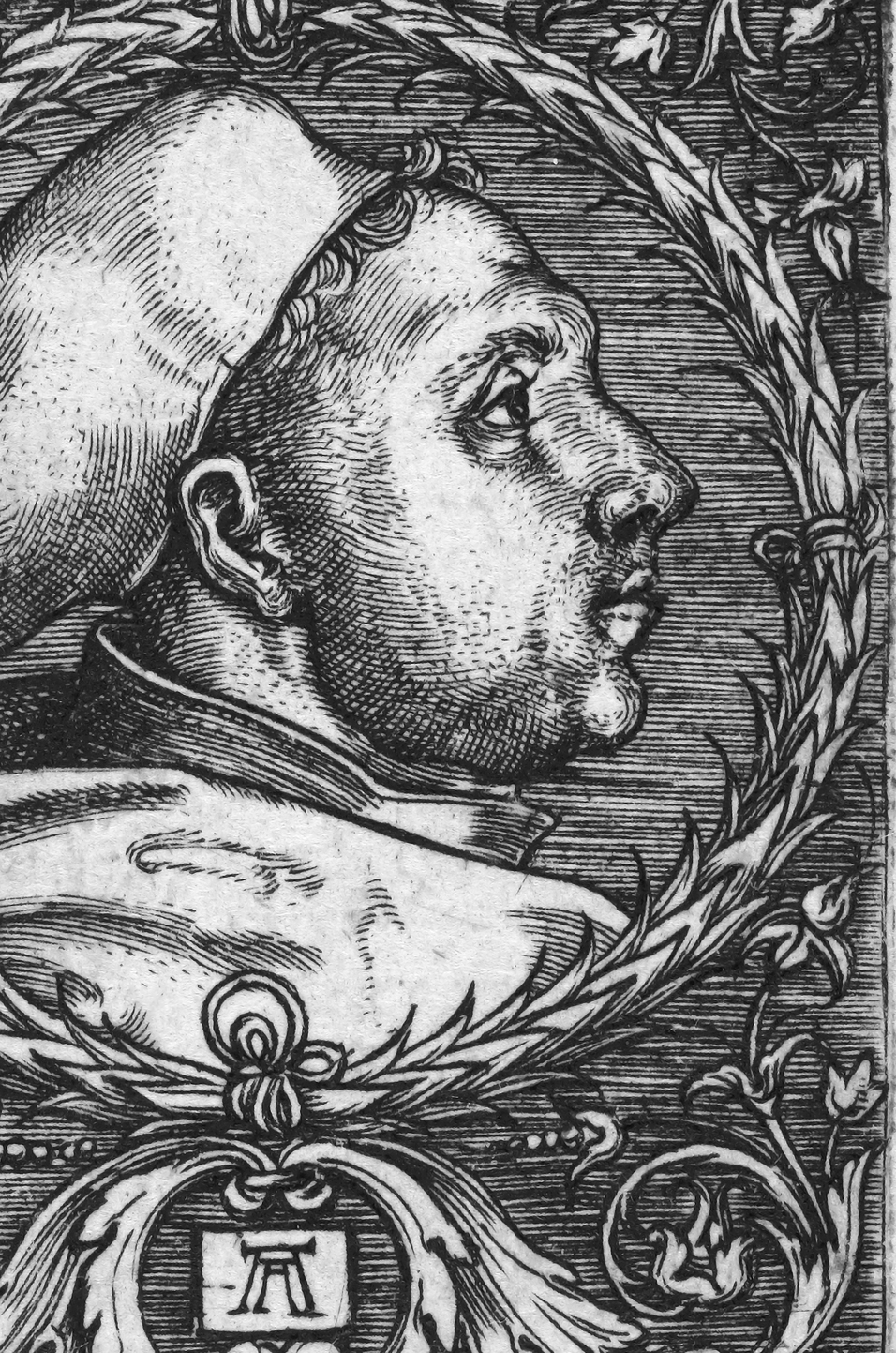

Dr. Martin Luther to Pope Leo X, May 1518, regarding his 95 theses

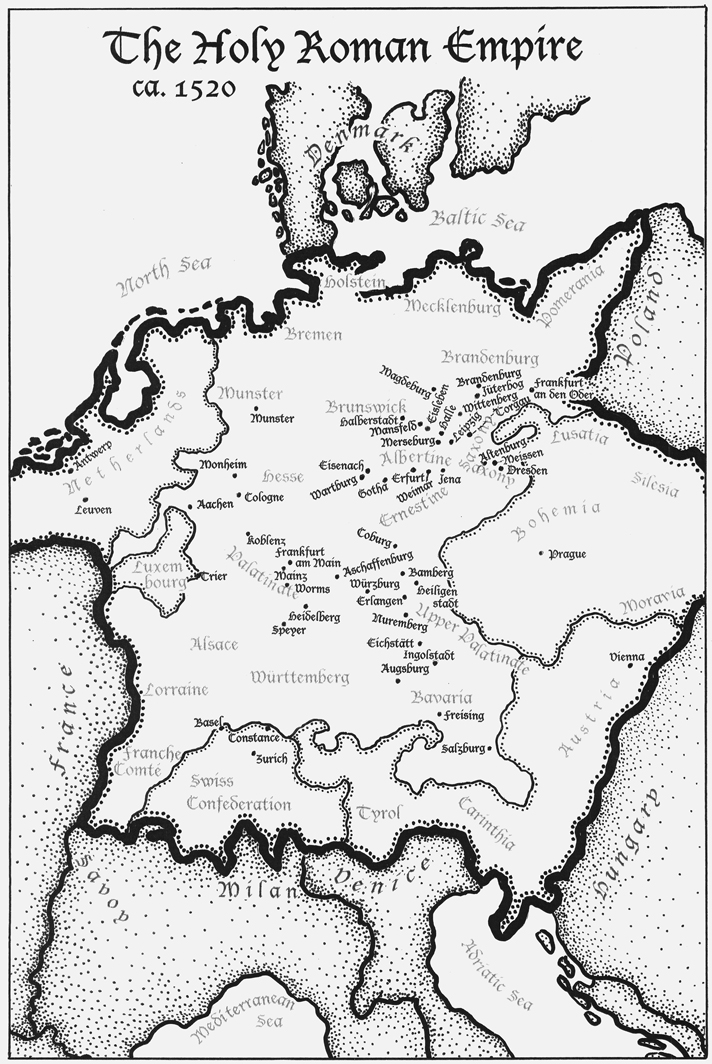

The Holy Roman Empire around 1520.

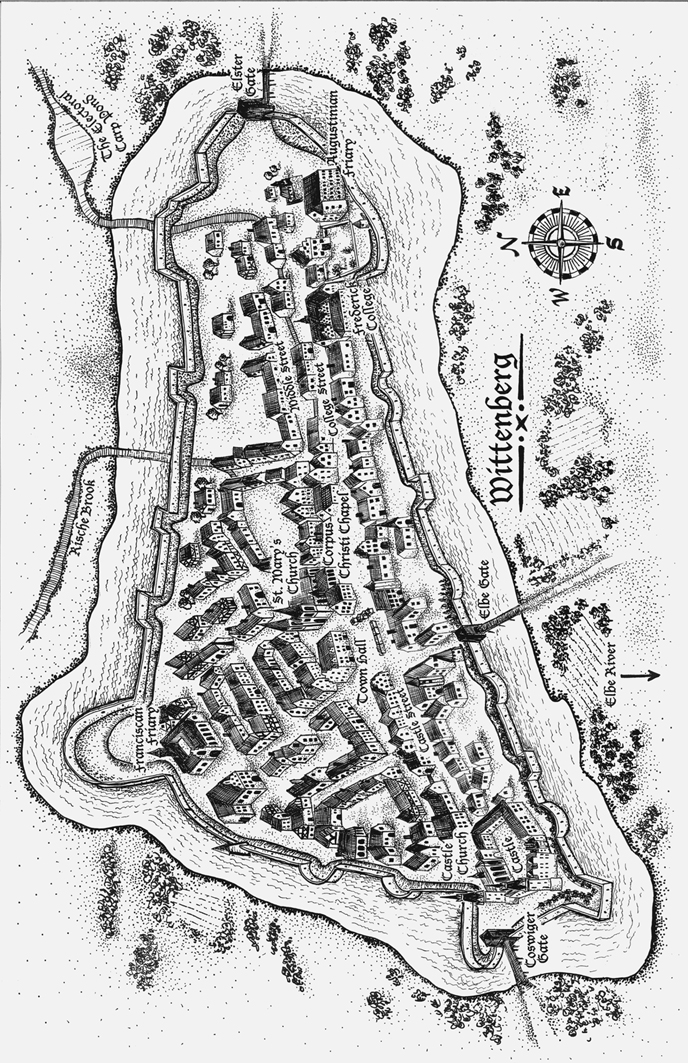

Wittenberg in Luthers Time.

OF MAKING MANY BOOKS THERE IS NO END, said Ecclesiastes in chapter 12, and he probably should have added, especially if theyre about Martin Luther. This is even more true whenever a big Luther anniversary comes along, like the one so enormously upon us in 2017: 500 whole years since the 95 upsetting theses.

But even in ordinary years, a fellow as prolific, and cheeky, and quotableas earth-rattlingas Luther, who is blamed or praised for changing just about everything in the Entire Western World, is going to have his story told more often than most, and in more ways than most too, because no story is ever told the same way twice, not even a famous one like his. As Luther said himself, even the everlasting gospel, the most famous story of all, was told in all sorts of waysbluntly, spun out, this way, thatso why wouldnt the story of his thoroughly corruptible flesh be too?

My own peculiar telling of his story, meant especially for readers who know the name Luther but arent exactly sure why, features not just my own sort of spinning, and shading, and coloring, but also just his first few trembly years of famei.e., from around the time in late 1517 when the obscure Brother Martin first put together his upsetting theses, until early 1522 when as a European-wide celebrity he came out of hiding and started putting his ideas to serious work. It also features a stubborn attempt to set the story relentlessly in his own world and to see through its eyes, not ours, so that we have a fighting chance to grasp the otherness and drama and absolute improbability of the whole astonishing thing. Which means it finally features (just to warn anybody hoping for monumental) Brother Martin, the flesh-and-blood sometimes-cranky friar-professor, instead of Luther, the giant bronze icon who changed the Entire Etc.

What Luther did (and didnt do) during these four-plus years would certainly have giant bronze-worthy consequences that lived on long after he was dust, but this book isnt about those (which are still being argued over). Its about the events of these few years alone, to stress how unlikely and fragile and bewildering they were, and thus to experience them as much as possible in the same nerve-wracking and uncertain way that he did, instead of with an eye roving toward the future, as if the outcome was never in doubt. Thats why, for example, I call him mostly Brother Martin or Dr. Martinnot because Im necessarily on his side, or am his special friend, but because people around him called him that (along with Father Martin). Strangers called him Luther, and so did his enemies, who also called him much worse: when the story shifts to their perspectives, I call him Luther too. But calling him only that would make him distant, when the point is to get up close.

Sure, there are a few exceptions to this Luther-worldly telling, to help move things along. Thus, even though numbers of Bible verses arent given (because there werent any numbered verses yet), the story is in mostly modern English (with Bible citations from the New Revised Standard Version), proposition and article take the more modern form thesis, distances are in miles and feet, dates are (eventually) in months and days, and places and names are in whatever form seemed best-suited, or most familiar, to English-readers, instead of always in the original or in Englishand so Kln is Cologne, Friedrich is Frederick, Franois is Francis, and Karel V is Charles V, but Johann, Johannes, Jan, and Hans are all as is, instead of John, while less famous Karels are as is too. And Martin, of course, is always just Martin.

A HEBREW-READING KNIGHT

Near Jena, in Thuringia. March 4, 1522. Shrove Tuesday, When Nothing is Ever as it Seems.

The young travelers were hungry and thirstyyes of course for knowledge, which was why theyd set out on this long journey in the first place, but at the moment theyd have gladly settled for a little food and drink instead. They were also wet and tired from being slapped around by a storm, and so a good fire and bed sounded just fine too. The problem was, it was Shrove Tuesday, and so when they finally entered Jena and started asking about rooms, all they heard at every single inn was that there were none.

Just as the two travelers, barely 19 years old, headed back out the gate toward a nearby village, to see what they could find there, a respectable-looking man who for some wondrous reason was also out in the godforsaken weather pointed them instead toward the much-closer Black Bear Inn, just outside Jenas walls. And blessd day, the host there certainly did have a room.