T he work related to this book has taken many twists and turns over the years and has benefited from the assistance of many friends, mentors, and colleagues. The original research was made possible by a number of fortuitous events, family connections, and people I met in the after-hours world. A number of people became famous and did not want to be named in the book; others were so eager to be involved they shared their field notes. The assistance they offered provided an important contribution to the making of this book in more ways than they know.

My former students are deeply thanked: Dr. Anahi Viladrich, Dr. Beverly Yuen Thompson, Dr. Cristina Dragomir, and Dr. Shatima Jones. Others who played a key role in the making of the material for this book: Isabella Bauso, Scott Beck, William Borstell, Frenchy Charleston, Jane Ciampa, Marlene Kim Connor, Leo Craig, Paul Craig, Patrick Devitt, Natalia Filippova, Selina Fulford, Rezvaneh Ganji, Tom Gerry, Monica Gomez, Alexandra Harocopos, Hakim Hasan, William B. Heimreich, Yukiko Kimura, Audee Kochiyama, William Kornblum, Jana Leo, Adrian Leung, Dara Levendosky, Noah Lucas, Ye Lui, Carmen Martinez, Jules Ostro, Jackie Oberlander, Phillip Oberlander, Yvette Pipers, Denise Poane, Dave Ray, Donald Smith, Sergeant Floyd Smith, Jason Smith, Sandra Smith, Teun Voeten, Conrad Walker, Diane Williams, Janice Williams, and Charles Winick.

At Columbia University Press I want to thank my anonymous reviewers and warmly acknowledge the help and guidance provided by my editor Eric Schwartz, Lowell Frye, Marisa Lastres, and the able art staff. Special thanks to James Alicea for his keen assistance and masterful art and to Sandra Smith and Kahlil Zulu Williams for their assistance.

People who remain anonymous by only one name: Alice, Buddy, Caprice, Conchita, Cookie, Dexter, Dustin, James, Janie, Jayson, Jessica, John, Madeline, Mavis, Mike, Nellie, Preciosa, Sonny, Tina.

All my students who assisted in the book with ideas, comments, and suggestions: Patrick Devitt, Dade Dodson, Isabelle Durbin, Tabitha Liucci, Lily Majteles, Jordon Marco, Nina Moss, Sarah H. Pitt-Cort, Mia Pumo, Hailey Redd, Amir Sharif, Amber Shooshani, Jacob Yusufov.

Although all of the aforementioned assisted in some way in the completion of this book, I take complete responsibility for any of its shortcomings.

1980s AND 1990s

The day was warm but not hot in the city. I left downtown and made my way uptown, going back to Harlem, where I did my fieldwork. I live in two worlds, the world of the academy by day and the life of the street by night, and I felt I had to reconcile them if I was ever to be the writerthe sociologistI wanted to be. I lived in Harlem but spent much of my time downtown in Village eateries, bars, and clothing shops, often mingling with people who I felt at times did not understand or always appreciate uptown hoi polloi. By the same token, the academic world only came in contact with my uptown compadres when they became the subject of some scholarly inquiry, poor people to study. I had not thought Id be following the advice of a bunch of professors telling me to ask questions of people in a Harlem nightclub, but that is what I was intending to do.

My brother-in-laws connect to the club made it easier to gain entre, but he did not assist me in getting into all the places I visited. But my being a social scientist is more or less intimately, organically, tied to the lifeworlds and communities I study. Thus, the issue concerning getting in raises the bar to a great degree because of what I was learning from doing this kind of work, where much of the worlds I decode is literally hidden in plain sight. I did not walk in with a notepad and start writing down what I saw and heard, but I did record when people were not around or in the bathroom, in my car, and on matchbook coverspart of my Malinowskian imponderabilia thing.

I did record only the people I knew well and those who asked I tape their stories. These taping situations took place outside the club proper and only a few times inside, when the place was empty. Had I not gotten permission, taping would have been foolishly difficult and dangerous to do covertlyplus it may have gotten me shot, even if I was the brother-in-law of the proprietor.

I believe the reconstruction of what I saw and heard can be considered another methodological tool, and since I am not trained as a professional court stenographer, most of my notes were only an approximation of what I heard and saw. Regardless, in order to write about what I saw and heard outside the limited formal interviews and to maintain a detailed, systematic journal of events, I had to be there. The account of what I saw and heard outside of the formal interviews with people is akin to keeping a detailed diary.

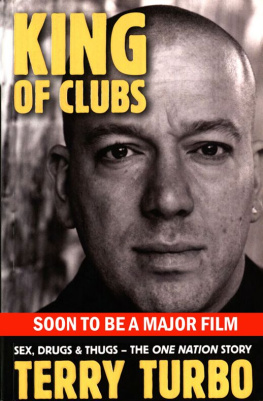

This is part and parcel of the ethnographers trade, especially in view of what is taking place at the clubmuch of which is illegal. As an ethnographer, I sometimes start with a question, but when it came to this work, I had many questions. What institutions in the community support a thuggish lifestyle? Where in the ghetto do people who make illegal money go? Where do they spend illegal money? Where are some of the places those who make illegal money hang out to show off their illegal finery? What goes on in these places where thug life is vibrant and active? Where do you go to do something indelicate and off-color or risqu, something illegal, something wrong? Where do you go if you are looking to visit Sin City? A few years ago, you might have gotten a glimpse of this world in the HBO series The Wire, in the scene where the boxer, Dennis, goes to a place that resembles an after-hours spot, where all kinds of deviant acts are taking place.

My sociologist colleague Paul Willis clearly makes several important points. In brief, the question is: What goes on here? But for an ethnographer, to find out whats happening means going out there to find out whats happening there. Willis writes about what he calls going half-native in describing the ethnographers role in field research; he says the role engages bodily presence. In other words, you must be there on the scene in body and mind; you must live through the event and have face-to-face contact or bodily traction, a kind of bodily interaction. This means you always have to go half-native, what he calls bodily implication; you had to have access to the action and pick up meaning as it happens. I soon learned that the after-hours club is one of the places that supports thug life and hustlers of various kinds, who go to such places to spend their money, so thats where I went.

2017

Once I was in the after-hours world, most people did not know anything about me except that I was a patron who hung around the spot. Most people I only saw one or two times; a few regulars came back once a month or so, but I basically spent little time with patrons after the first night. People did not know I was doing any kind of study. My note taking was never obvious, though I always had a notebook or journal with me and would capture conversations or snippets Id overheard. I developed several strategies; one was to listen to two conversations taking place on either side of me.

This meant my hearing was quite selective; the approach here is to reconstruct the conversations. I would piece together parts of the speech and make whole sentences as needed. If I heard a joke, I would just jot down the punch line because recalling the punch line made the rest of the joke easier to remember.

I was aided by the work of my contacts, what Hakim Hasan calls bridge persons, who provided notes, introduced me to further contacts, and showed me around areas I had not been privy to. In going over my Le Boogie Woogie material, I realized I needed to provide a snapshot of what the after-hours world is like today (20162019), for contrast. This made it possible to gain an understanding of cultural meanings and provide necessary details of the intensive period of the work. In that sense Murphys is the shadow of Le Boogie Woogie.