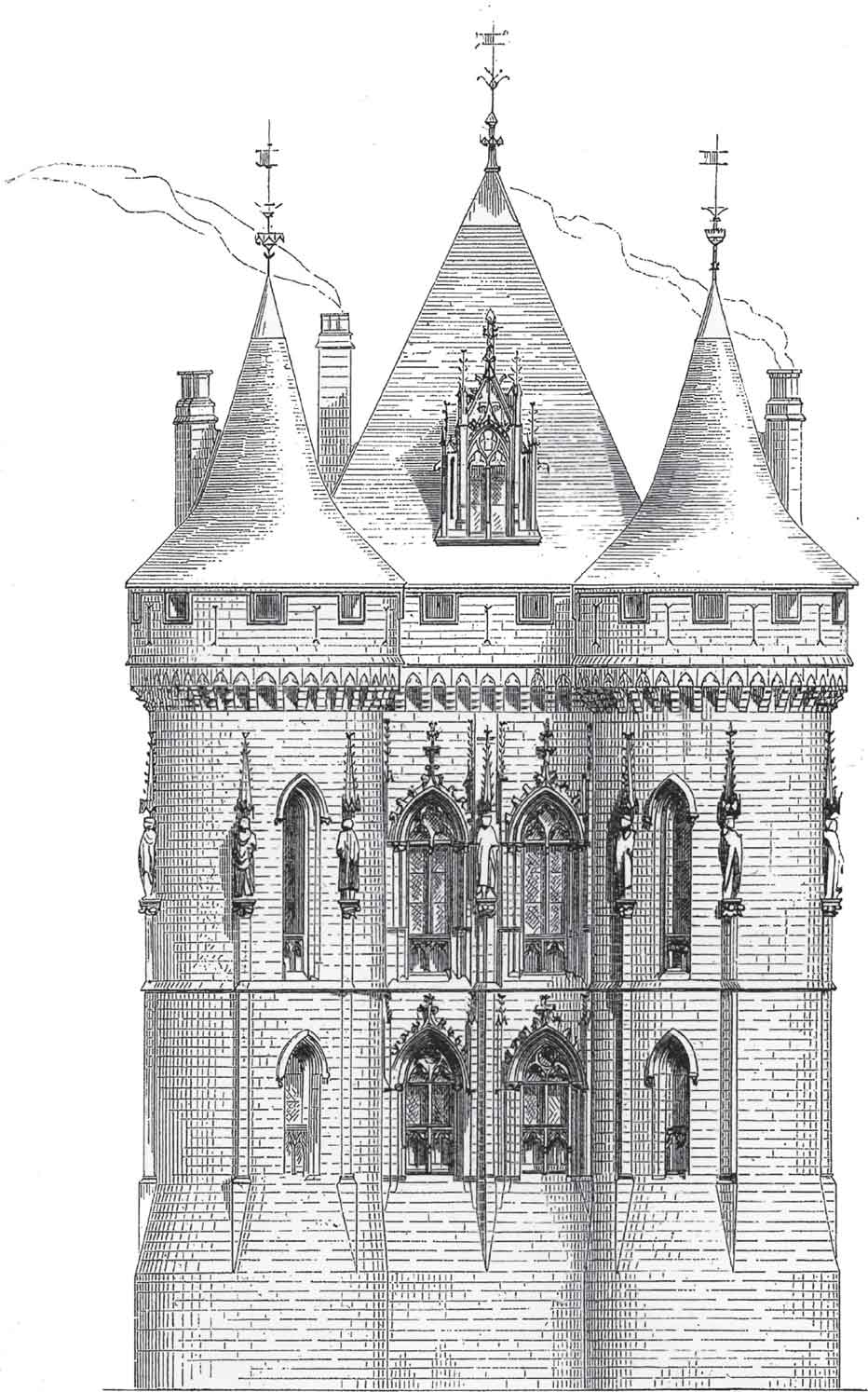

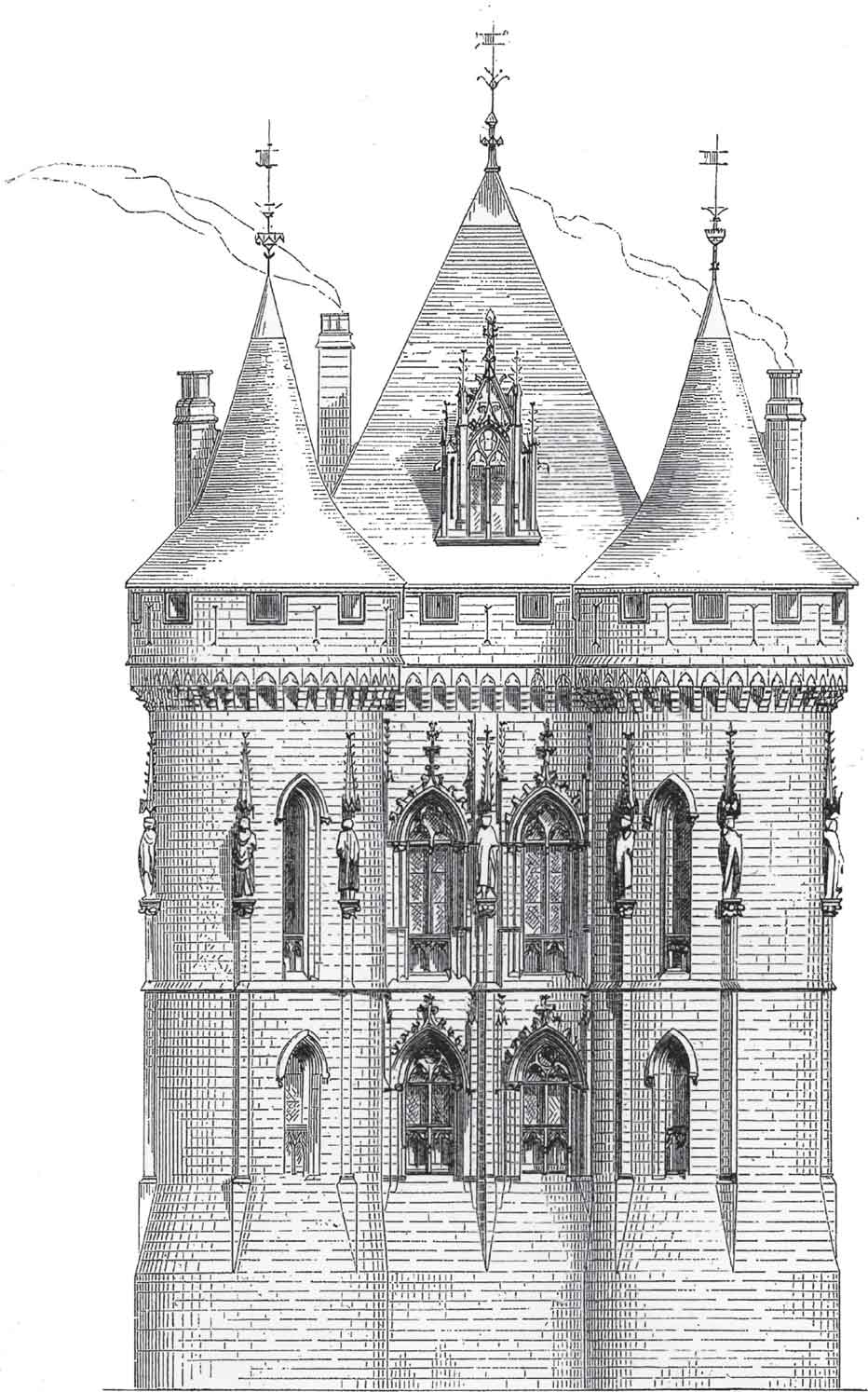

Poitiers, Ducal Palace; conjectural restoration of the Maubergeon Tower by Viollet-le-Duc (1868)

Published in the United Kingdom in 2016 by

OXBOW BOOKS

10 Hythe Bridge Street, Oxford OX1 2EW

and in the United States by

OXBOW BOOKS

1950 Lawrence Road, Havertown, PA 19083

Anthony Emery 2016

Hardcover Edition: ISBN 978-1-78570-103-0

Digital Edition: ISBN 978-1-78570-104-7

Kindle Edition: ISBN 978-1-78570-105-4

PDF Edition: ISBN 978-1-78570-106-1

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Emery, Anthony.

Title: Seats of power in Europe during the Hundred Years War : an architectural study from 1330 to 1480 / Anthony Emery.

Description: Oxford : Oxbow Books, 2015. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2015033829 | ISBN 9781785701030 (hardcover) | ISBN 9781785701047 (digital)

Subjects: LCSH: Hundred Years War, 1339-1453--Social aspects. | Hundred Years War, 1339-1453--Political aspects. | Europe--Kings and rulers--Dwellings--History. | Architecture and society--Europe--History--To 1500. | Architecture and state--Europe--History--To 1500. | Royal houses--Europe--History--To 1500. | Power (Social sciences)--Europe--History--To 1500. | Palaces--Europe--History--To 1500. | Castles--Europe--History--To 1500. | Fortification--Europe--History--To 1500.

Classification: LCC DC96.5 .E46 2015 | DDC 944/.0251--dc23 LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015033829

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the publisher in writing.

Printed in Malta by Melita Press Ltd

For a complete list of Oxbow titles, please contact:

UNITED KINGDOM

Oxbow Books

Telephone (01865) 241249, Fax (01865) 794449

Email:

www.oxbowbooks.com

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

Oxbow Books

Telephone (800) 791-9354, Fax (610) 853-9146

Email:

www.casemateacademic.com/oxbow

Oxbow Books is part of the Casemate Group

Contents

Notes:

Historical Review

Architectural Study

Preface

This study considers the residences of the crowned heads and the royal ducal families of the countries involved in the Hundred Years War between England and France. Though they were the leading protagonists and therefore responsible for the course of the war, do their residences reflect an entirely defensive purpose, a social function, or the personality of their builders?

The War is usually ascribed to the period from 1337 to 1453 but this study has been extended by a further thirty years as the political and architectural repercussions of the War continued to be felt in England and even more so in France until the deaths of Louis XI and Edward IV.

During its course, the War extended to other parts of Europe. This particularly applied during the fourteenth century when it involved the county of Flanders and the states of Aragon, Castile, Portugal, and the papacy at Avignon. Scotland and Flanders continued to participate during the fifteenth century. The residences of their rulers are therefore of equal relevance and significance to those of France and England.

With a subject of such broad span, this study has concentrated on sixty properties extending from the castles at Windsor and Kenilworth to those at Saumur and Rambures, and from the palaces at Avignon and Seville to the manor-houses at Germolles and Launay. A number of subsidiary or associated properties are also considered in the more broad-themed sections.

Castle and house studies in England and to some extent in France are currently in a state of flux arising from recent re-interpretations and revisionism, as well as the appreciation of the complex and differing roles of such residences in the political, social, and cultural circumstances of the time. These contrasts can be symbolised by comparing the starkness of Tarascon Castle with the contemporary decorative retreat of the duke of Berry at Mehun-sur-Yvre. Few castles and palaces in Europe are alike, despite the common background of the war. What this overview considers are the differences in layout, style and purpose including ceremonial needs and social control of some of the most commanding residences of the later middle ages.

This study is intended to be no more than an introductory overview, but as many students have a limited knowledge of the political background of the later middle ages, each region and its residences are prefaced by supporting historical and architectural surveys to help position the properties against the contemporary military, financial, and aesthetic backgrounds.

The subject spans an extremely broad and complex landscape which leaves many areas untilled. But if it shows the range and complexity of the scene, then it may lead to a less narrow approach to castle and house studies.

Titles have been anglicised but this only occasionally applies to their names. The Bibliography for the individual buildings immediately follows the relevant text. More broad-based studies historical and architectural are listed in the concluding Select Bibliography.

INTRODUCTION

THE HUNDRED YEARS WAR: 13301480

The phrase The Hundred Years War, first used by Desmichels in 1823, may be a highly convenient term to describe the attenuated late medieval conflict between England and France, but it is conceptually misleading. It is not so much that this struggle for supremacy extended well beyond the traditional limits of 1337 to 1453, but the fact that it was not a continuous war but a series of vicious conflicts, separated by extended periods of uneasy peace or truce marred by sporadic hostilities. Nor was it simply between the Plantagenet and Valois dynasties, but also between them and fiefs such as Brittany, Flanders, and Burgundy who chose to support one side and then the other as the political or economic situation demanded. To a lesser extent, it also involved several other European countries, creating a complex pattern of political, financial, economic, military and social consequences. Though this study is precise in its scope, one consequence common to this as to most other aspects of the war is that a conflict which began between protagonists who only knew the feudal order was concluded about 150 years later by a society increasingly dominated by trade and finance at the dawn of the Renaissance.

The origins of the conflict were deep rooted and lay at least as far back as the Angevin inheritance of Aquitaine in the mid-twelfth century. The more immediate cause was the dynastic crisis in France in the years following the death of Philip IV in 1314 and his short-lived successors, and the feudal responsibilities and family conflict inherent in the close relationship between the royal houses of France and England. It was also about the gradual development of national characteristics and consciousness, particularly in France with the associated concept of a single state centred on Paris, and to it opposition by a number of great princes and vassals of the French crown anxious to develop their own political independence, particularly the count of Flanders and the king of England as duke of Aquitaine.

Nor were the key protagonists equal. France was the wealthiest kingdom in western Europe with a population estimated at between 15 and 21 million inhabitants. Though agriculturally rich, the royal domain embraced only about half the kingdom with the remainder essentially held by four almost independent fiefs of the French king Aquitaine, Brittany, Burgundy and Flanders. The machinery of government, centred on Paris, was expanding though with difficulty in the mountainous south, but Philip IV (12851314) had won his conflict with the papacy, with the added benefit of the popes proximity after his relocation from Rome to Avignon from 1309. England and Wales was a poorer country with a population of about four and a half million, principally spread across central and southern England, and lacking the benefit of a substantial manufacturing industry. On the other hand, it was far more cohesive than France, with a well-oiled central administration, a more efficient means of levying taxes and raising an army, and far greater loyalty from the leading magnates. There was, though, a potential danger along the northern frontier if Scotland formed an alliance with France. Neither country believed that the conflict was more than a quarrel about feudal sovereignty nor that it would extend beyond a few seasons of warfare. This might have been so, had not Edward III formally assumed the title and arms of the king of France in 1340, inaugurating a new posture in Anglo-French relations, and making it impossible for either side to compromise.

Next page