THE AGE OF CHIVALRY

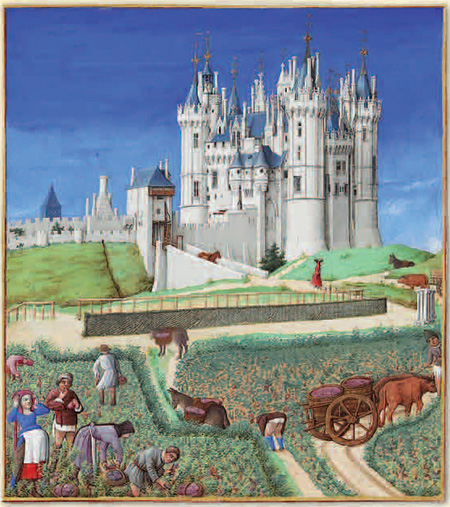

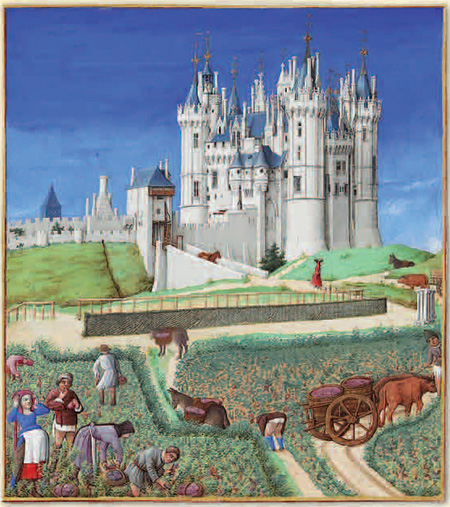

A pastoral scene is shown in this image from the Trs Riches Heures du Duc de Berry, a 15th-century book of hours.

THE AGE OF CHIVALRY

THE STORY OF MEDIEVAL EUROPE, 1000 TO 1500

HYWEL WILLIAMS

New York London

2011 by Hywel Williams

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by reviewers, who may quote brief passages in a review. Scanning, uploading, and electronic distribution of this book or the facilitation of the same without the permission of the publisher is prohibited.

Please purchase only authorized electronic editions, and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of the authors rights is appreciated.

Any member of educational institutions wishing to photocopy part or all of the work for classroom use or anthology should send inquiries to Permissions c/o Quercus Publishing Inc., 31 West 57th Street, 6th Floor, New York, NY 10019, or to .

ISBN 978-1-62365-276-0

Distributed in the United States and Canada by Random House Publisher Services

c/o Random House, 1745 Broadway

New York, NY 10019

www.quercus.com

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

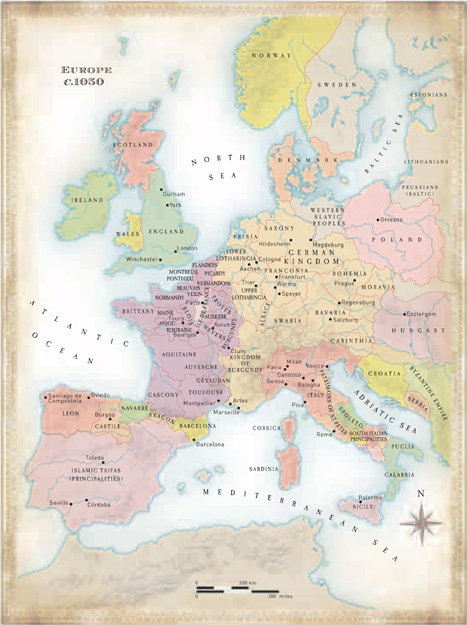

Three distinctive civilizations developed in western Eurasia and North Africa following the fifth century collapse of the Western Roman empires authority. The Greek empire of Byzantium was centered on the eastern Mediterranean while the civilization of Islam became predominant across North Africa and in the Middle East. European civilization incorporated the western Mediterranean territories but it also acquired a new axis which extended northwards to include areas that had been peripheral to classical Roman antiquity. These three cultures were the sibling civilizations of ancient Rome, and western Europe came to define itself as the bastion of Latin Christendom as opposed to the Greeks eastern Orthodoxy. Up until at least the year 1000 Europes level of cultural, intellectual and material development was clearly inferior to that attained by Byzantium and the Islamic states. During the central or high Middle Ages that extended from the 11th to the 13th centuries the continent started to rival its two neighboring powers in terms of political effectiveness, military success and cultural expansiveness. By the 15th century Europeans were asserting supremacy over their erstwhile rivals and superiors. The means by which this great transformation came to pass form the subject matter of this book.

Social structures were reorganized at a profound level in western Europe from c.500 onward: the traditions of imperial Rome now yielded to those of the Germanic peoples, such as the Franks and the Lombards, who had migrated to the south and west. New kingdoms were thereby established in western Europe, and monarchys institutional authority turned former citizens into subjects. A process of Christianization was encouraged by missionaries, sponsored by rulers and often imposed on subjugated pagan peoples, and monasticism became the supreme expression of European religious life.

Europe had been a geographical term since Graeco-Roman antiquity but the word acquired a cultural and political significance during Charlemagnes reign as king of the Franks (768814). The scale of his victories gave Charlemagne a dominion over most of the territories which had once comprised the Western Roman empire, and in the year 800 he was crowned emperor by Pope Leo III. Charlemagnes heirs and successors however failed to maintain his expansionist momentum, and after the division of the former Carolingian empire (843) European kings found it difficult to raise the armies needed to enforce their authority. A century-long period of strain and danger followed with Magyar invasions from the east and Viking incursions from Scandinavia undermining Europes recovery and self-confidence.

Hardened by these battles, European military and political leaders were able to regain the initiative by the late tenth century, and the papacys decision to grant an imperial crown to the German king Otto I in 962 marks the start of the institution which would later be termed the Holy Roman Empire. Demographic growth, urban development, and a burgeoning sense of national identityas well as the papacys assertion of its own independent powerare the hallmarks of the central Middle Ages. From the 11th century onward the chivalric code, which inculcated the virtues of valor, courtesy, honor and loyalty, achieved a widespread diffusion among the European lites. Chivalrys influence transcended the ethics military origins, and its celebration of the cult of love, both human and divine, had a profound impact on social conduct, religious idealism and aesthetic inspiration.

The phrase medium aevum was coined during the early 17th century by French and English historians of jurisprudence, and its vernacular equivalents, moyen age, Middle Ages and medieval, were adopted subsequently. These authors also popularized the notion that feudalismanother word they inventedwas the universal form of social life in western Europe by the 11th century and that it lasted for at least another 300 years. The terms feudum (or fief) and feodalitas (services connected with the feudum) refer to a form of property holding which was especially common in France and England. But the way in which European societies changed in the post-Roman and medieval centuries inevitably assumed many different guises, and an uniform feudal system did not exist at any stage in the history of medieval Europe. An assertion of lordship however did become widespread and its exercise showed how power at local, regional and national levels could be established by a mutual exchange of vows between superiors and inferiors. Obligations of service might then be incurred by those sometimes called vassals and promises of protection would be made by the relevant lord.

During the 14th century Europeans had to cope with a series of both natural and man-made disasters: widespread famines, the Black Death of 1348 and subsequent years, as well as the mid-century collapse of Italian banks. Technological change meant that warfare became both more expensive financially and increasingly devastating in its human impact. Expansion and development halted in both the towns and the countryside, and Europes population, which had stood at some 70 million in 1300, was almost halved. European resilience is nonetheless the key feature of this renewed time of trial with first the rural areas and then the urban centers being rapidly repopulated. The intellectual, political and social changes associated with an initially Italian renaissance evolved out of late medieval society, and are inconceivable outside that context. Personal enterprise, intellectual curiosity, and institutional responsiveness to change: these defining characteristics of European civilization were formed during the medieval centuries and it was that legacy from its past which enabled the culture to survive, evolve and flourish.

Next page