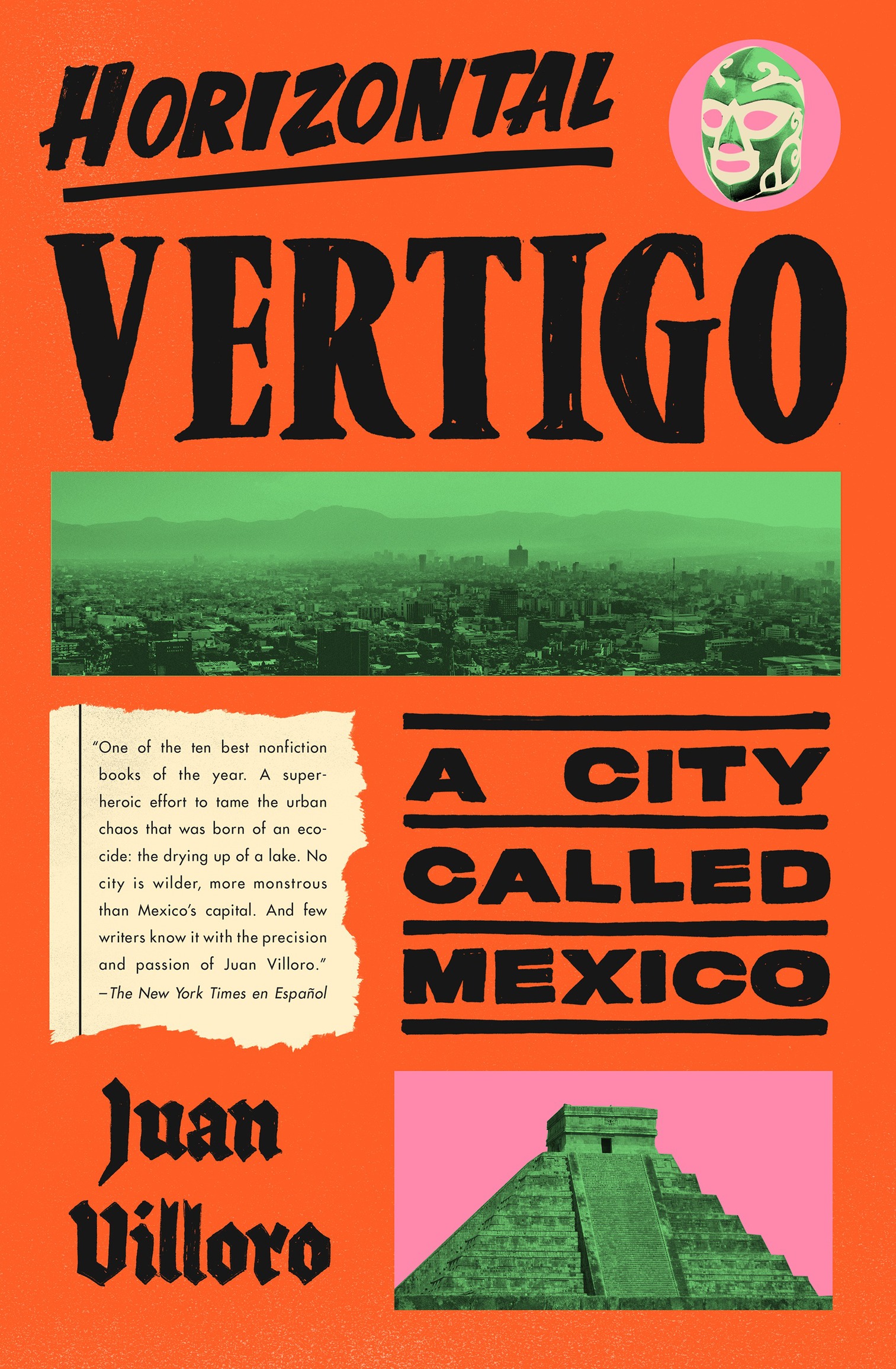

Juan Villoro - Horizontal Vertigo: A City Called Mexico

Here you can read online Juan Villoro - Horizontal Vertigo: A City Called Mexico full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2021, publisher: Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, genre: Art. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Horizontal Vertigo: A City Called Mexico

- Author:

- Publisher:Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group

- Genre:

- Year:2021

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Horizontal Vertigo: A City Called Mexico: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Horizontal Vertigo: A City Called Mexico" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Horizontal Vertigo: A City Called Mexico — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Horizontal Vertigo: A City Called Mexico" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Translation copyright 2021 by Alfred MacAdam

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Pantheon Books, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York, and distributed in Canada by Penguin Random House Canada Limited, Toronto. Originally published in Mexico as El vrtigo horizontal by Almada Ediciones S.A.P.I. de C.V., Mexico City, in 2018. Copyright 2018 by Almada Ediciones and Juan Villoro. Prologue copyright 2018 by Nstor Garca Canclini

Pantheon Books and colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Villoro, Juan, [date] author. MacAdam, Alfred J., [date] translator.

Title: Horizontal vertigo : a city called Mexico / Juan Villoro ; translated from the Spanish by Alfred MacAdam.

Other titles: Vertigo horizontal. English.

Description: First American edition. New York : Pantheon Books, 2021.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020031282 (print). LCCN 2020031283 (ebook). ISBN 9781524748883 (hardcover). ISBN 9781524748890 (ebook).

Subjects: LCSH : Mexico City (Mexico)Civilization21st century. Mexico City (Mexico)Social life and customs21st century.

Classification: LCC F 1386 . V 5713 2021 (print) | LCC F 1386 (ebook) | DDC 972/.53dc23

LC record available at lccn.loc.gov/2020031282

LC ebook record available at lccn.loc.gov/2020031283

Ebook ISBN9781524748890

www.pantheonbooks.com

Cover images: (top) sirtravelalot/Shutterstock; (middle, Mexico City) Luis Emilio Villegas Amador/EyeEm/Getty Images; (bottom, Pyramid of Kukulkan, Chichen Itza) Kofi Adjebeng/EyeEm/Getty Images

Cover design by Tyler Comrie

ep_prh_5.6.1_c0_r0

Regarding these things I artlessly express, which cause astonishment when seen and give so much pleasure, and about which I could say a great deal, well, when I think about them, Im really shocked, because they bear such a strangeness that even I cant manage to understand what they are.

Juan de la Cueva , Epistle to Master Snchez de Obregn, First Corregidor of Mexico

We arent united by love but by horror.

Thats probably why I love it so much.

Jorge Luis Borges , Buenos Aires

Those of us who inhabit a megalopolis are made uncomfortable by some of the studies carried out by social scientists. Is the order they create to group facts believable? Is their organization of numbers, of kinds of behaviors, of the frequency charts of accidents and thefts over the course of years all that well reasoned for those of us who on a daily basis experiment with less safe streets at different hours of the day or night and try to put up with the traffic and other kinds of chaos all in order to find meaning and relief in the great disorder?

This book is not lacking the statistics or real estate and police accounts we use to explain Mexico City, but to decipher the surfeit and whimsies of living in this place, where the figure of the flneur who strolls along intending to get lost on the trail of a surprise was replaced by that of the deported person (who cant go home again), Juan Villoro gathers together those who narrated the city and discusses things with them. He knows the witnesses who documented Mexico City when it was only the historic center, then he passes through a tide of low houses and wonders where were going when towers 820 feet high spring up. Are we really exaggerating when we believe those heights exceptional?

Our doubts are put to the test by Horizontal Vertigo when it compares our megalopolis with facts and stories about Buenos Aires and New York or when it recalls what shocked so many foreigners in other times about the capital of Mexico. He weaves together ethnographies of the Mixcoac neighborhood he lived in as a child with ceremonies in which the Cry of Independence is celebrated or when national heroes (Obregn) and foreign heroes (Hernn Corts) are honored. As an expert who participated in the group that produced the recent constitution of Mexico City, Villoro notes all the clues as to how it was written and forgotten. He contrasts official excesses with the stories of those who administer daily monotony: office boys, conscripts, wrestlers, the accidental installation artists who decorate public parking lots or hang shoes on electric lines.

At times these investigations are dense, like those, as Clifford Geertz says, that anthropologists carry out. For example, the well-documented study of street children. But his gaze is just as incisive in more ludic accounts such as that on the Tepito market, the Chopo market, the bureaucracy of the capital, the holidays, and the theme parks. The pleasure of the text derives from this uninhibited mix of styles and uncertainties.

There is an element of Ill bet I can do this in trying to write one book about a city where people live in millions of different ways. Villoro accepts the challenge by taking charge of different generations in a single family, without turning his back on the adventures his own has had. In this palimpsest of memories, of abandoned houses and others where people live as if they were abandoned, of infinite and infinitely varied interior patios, intermediary terraces, storage closets, cafs, and the poems that evoke them, of gas stations right next to the mausoleums of heroes, temples dedicated to lost causes, and simple weather issues, its almost scandalous, the author says, that so many cities bear the same name.

The infinite demands strategies to become something close to us. Making things that are disconcertingly near to us, the thing that reduces distances: thats the chroniclers ingeniousness. But how do you go about setting up a book, a coherent or at least credible interpretation, by means of this total immersion journalism that ventures into territories and ruins that are so diverse? There is no interpretation, but there is a book. The books strategy is to isolate those points where disorder manifests itself in ways that seem urban, behind the trademarks and logos, those toponymics of No Place, as John Berger calls them.

Shortly after reading Villoros manuscript, actually, his palimpsest, there appeared a book about another multicultural city, a book that had its orders (never just one): Jorge Carrins book on Barcelona. That book made Villoros clearer to me. Why when the various examples of a metropolis are defined by pedestrians, the number of cars, speed, or traffic, does Carrin analyze the Catalan capital using side streets? Because, says Carrin, in each side street we find the affirmation and negation of the entire city. Those passageways, hyperlinks, connections between places or concepts that are neither roads nor streets, ignore or elude by pausing the vertigo of traffic. Barcelonas side streets are footnotes, tunnels that take us to what is beneath the page, beneath the urban text.

Villoro and Carrin, heterodox disciples of Walter Benjamin, ferret out metropolitan meanings digging around in the detours through which their respective cities at least become legible if not organized. Their points of reference are closer to the scraps of paper on the streets, what people talk about, their ways of strolling around and inventing side streets than they are in maps without garbage, than the division of Mexico City in administrative zones and other arbitrary notions.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Horizontal Vertigo: A City Called Mexico»

Look at similar books to Horizontal Vertigo: A City Called Mexico. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Horizontal Vertigo: A City Called Mexico and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.