Carroll B. Johnson - Don Quixote: The Quest For Modern Fiction

Here you can read online Carroll B. Johnson - Don Quixote: The Quest For Modern Fiction full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 1990, publisher: Twayne Publishers, genre: Art. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Don Quixote: The Quest For Modern Fiction

- Author:

- Publisher:Twayne Publishers

- Genre:

- Year:1990

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Don Quixote: The Quest For Modern Fiction: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Don Quixote: The Quest For Modern Fiction" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Don Quixote: The Quest For Modern Fiction — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Don Quixote: The Quest For Modern Fiction" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

This book made available by the Internet Archive.

for Amy

Note on the References and Acknowledgments

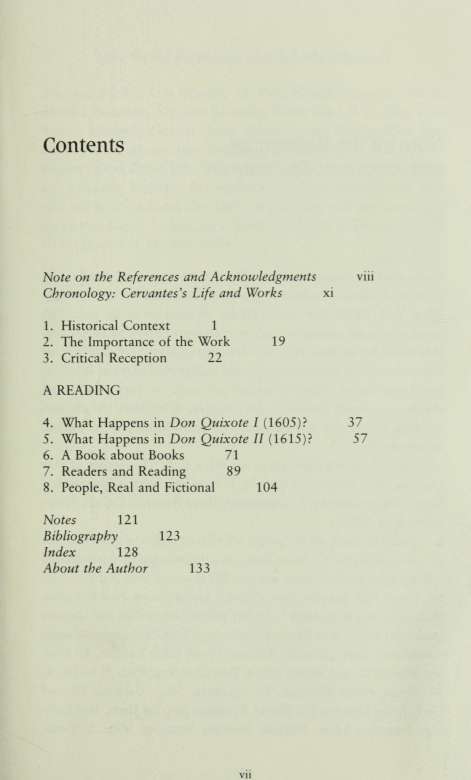

I have used the Norton Critical Edition's Ormsby translation of Don Quixote, revised and edited by Joseph R. Jones and Kenneth Douglas (New York: W.W. Norton, 1981) for all citations in the text. This translation is the smoothest and most accurate I know and is particularly useful for students because it contains excerpts from several other literary texts that constitute important background material as well as ten classic studies. Many references are simply to part (I or II) and chapter (in Arabic numerals), for example, 11:14. Since the chapters are short, the passage in question can be readily located by this method in any edition.

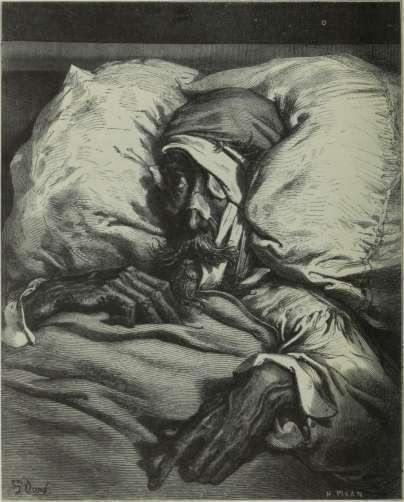

Gustave Dore's illustrations are taken from The History of Don Quixote, by Cervantes, edited by J. W. Clark, with a biographical notice of Cervantes by T. Teignmouth Shore (London: Cassell, Petter, andGalpin, 1906).

I need to thank all the people who have taught me to think about Cervantes and Don Quixote. Some are acknowledged in the notes and bibliography, but too many are not. My teachers: Don Americo Castro, Ernest Hall Templin, Steve Gilman, Joe Silverman, Paco Marquez, Dick Andrews, Raimundo Lida. My fellow cervantistas and Quixote freaks: Jay Allen, Juan Bautista Avalle-Arce, Jean Canavaggio, Joaquin Casalduero, Tony Cascardi, Anthony Close, Louis Combet, Ed Dudley, Manuel Duran, Arthur Efron, Dan Eisenberg, Ruth El Saffar, R. M. Flores, Alban Forcione, Ed Friedman, Mary Gaylord, Michael Gcrli, Javier Herrero, Jim Iffland, Monique Joly, Joe Jones, Tom Lath-rop, Francisco Lopez Estrada, Howard Mancing, Mike McGaha,

Note on the References and Acknowledgments

Mauricio Molho, Luis Murillo, Jim Parr, Helena Percas de Ponseti, Richard Predmore, Augustin Redondo, Walter Reed, E. C. Riley, Elias Rivers, Elizabeth Rhodes, Harry Sieber, George Shipley, Nick Spa-daccini, Bob terHorst, Alan Trueblood, Eduardo Urbina, Bruce Ward-ropper, Alison Weber, John Weiger, Edwin Williamson, Diana Wilson, and Francoise Zmantar. My students at UCLA, especially the ones who ask hard questions. The editor of this series and fast man with a telephone, Robert Lecker. Anne Jones and Lewis DeSimone of G.K. Hall. My analyst. My wife Leslie.

"Don Quixote in bed, about to receive Dona Rodriguez' Illustration by Gustave Dore.

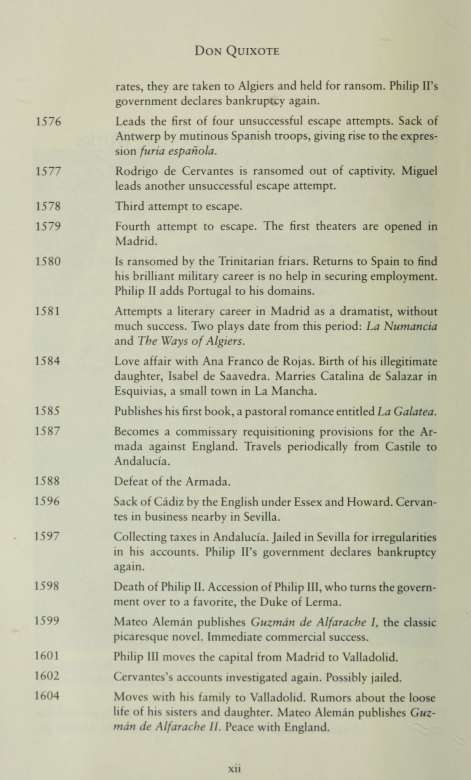

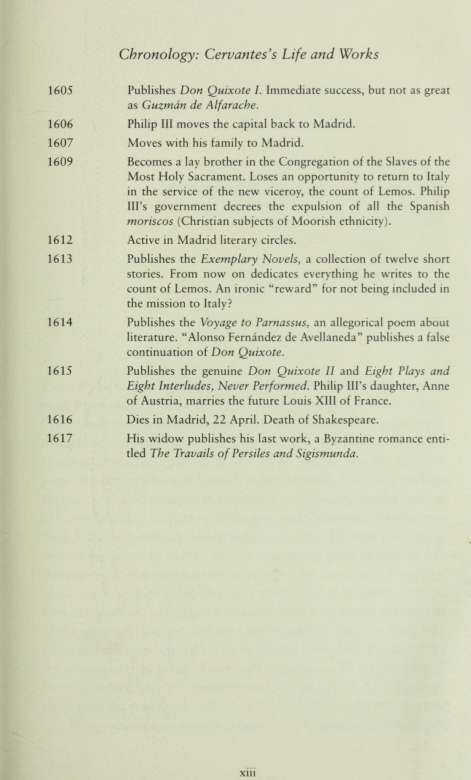

Chronology: Cervantes's Life and Works

1547 29 September? Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra is born in the

university town of Alcala de Henares, the son of Rodrigo de Cervantes, a surgeon, and his wife, Leonor de Cortinas. Fourth of a family of seven. Baptized 9 October. First Index of Prohibited Books. First Statutes of Purity of Blood.

1553 Death of Francois Rabelais.

1554 Publication of the first picaresque novel, Lazarillo de Tormes.

1556 Charles V (Carlos I of Spain), Holy Roman Emperor, abdicates in favor of his son, Philip II.

1557 Philip IPs government declares bankruptcy.

1558 Death of Mary Tudor, Queen of England. She is succeeded by Elizabeth I.

1559 Publication of the first pastoral romance, Jorge de Monte-mayor's La Diana.

1561 Madrid becomes the official capital of Spain.

1563 The Council of Trent (1545-63) ends, reaffirming conservative Roman Catholic doctrine and initiating the Counter-Reformation. Birth of Lope de Vega.

1564 Birth of Shakespeare.

1565 Revolt of the Spanish provinces in the Low Countries.

1567 Publishes his first poems.

1569 In Rome, in the service of Cardinal Giulio Acquaviva; falls in

love with Italian culture.

1571 The Christian fleet, commanded by Don Juan de Austria, de

feats the Turks at Lepanto. Cervantes fights heroically, losing the use of his left hand.

1575 After residing in Italy for some time, sails for Spain with his

brother Rodrigo on the galley Sol. Captured by Muslim pi

Historical Context

Every book is about its own time and place. Maybe that's not what is most interesting to us in the late twentieth century, but it's a fact. Critics have always observed that Cervantes makes all the social types of his society, from prostitutes and mule drivers to ecclesiastics and the grandest aristocrats, pass in review in his pages. Yes, the Quixote presents a compendium of Spanish society in 1600, but that is perhaps the least profound aspect of it. Important social issues, literally matters of life and death, are taken up in the text, and Cervantes's treatment of them is characteristically antiestablishment. Don Quixote is a revolutionary document in its own time, a courageous piece of writing, but this important dimension is lost to us unless we can acquire some idea of the social context in which it was produced and to which it refers. Certain things in Cervantes's text make sense only within the context of the sixteenth century, and we only succeed in impoverishing ourselves and our experience if we try to pretend they're not there, or if we try to read only in terms of our own experience. We simply have to learn something about Spain between 1500 and 1615. As it happens, those were exciting times with more than a little resemblance to ours. In my student days the first work of Don Quixote criticism people

Don Quixote

usually heard about was a book that appeared in 1925 by a man named Americo Castro and called El pehsamiento de Cervantes (Cer-vantes's thought). Castro in 1925 saw the Quixote as the fruit of all the intellectual currents of the Renaissance. He demonstrates that Cervantes was at the very least abreast of what was going on elsewhere in Europe. Castro especially singles out Cervantes's familiarity with the revival of Platonism or neoplatonic philospohy in Italy, with the Italian literature of the Renaissance, and above all with the Christian humanism of Erasmus of Rotterdam.

Humanism, as the term was understood in the Renaissance, is a strategy for yielding up understanding based on the belief that the written text is the source of knowledge, and that consequently the scholar's job is to understand and elucidate the text. This is not a particularly remarkable notion in 1990. Professors of literature consider themselves humanists. Our job is to make the texts of earlier periods accessible to our studentsin fact, this chapter of this book and a great deal of literary scholarship in general are examples of a degraded form of Renaissance humanism. But it was pretty revolutionary around 1450. Erasmus and his fellow humanists were practitioners and champions of what is called philology, or the New Learning. It will be helpful to consider the New Learning in opposition to its rival, the Old Learning or scholasticism.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Don Quixote: The Quest For Modern Fiction»

Look at similar books to Don Quixote: The Quest For Modern Fiction. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Don Quixote: The Quest For Modern Fiction and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.