Cervantes Don Quixote

THE OPEN YALE COURSES SERIES is designed to bring the depth and breadth of a Yale education to a wide variety of readers. Based on Yales Open Yale Courses program (http://oyc.yale.edu), these books bring outstanding lectures by Yale faculty to the curious reader, whether student or adult. Covering a wide variety of topics across disciplines in the social sciences, physical sciences, and humanities, Open Yale Courses books offer accessible introductions at affordable prices.

The production of Open Yale Courses for the Internet was made possible by a grant from the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation.

RECENT TITLES

Paul H. Fry, Theory of Literature

Roberto Gonzlez Echevarra, Cervantes Don Quixote

Christine Hayes, Introduction to the Bible

Shelly Kagan, Death

Dale B. Martin, New Testament History and Literature

Giuseppe Mazzotta, Reading Dante

R. Shankar, Fundamentals of Physics: Mechanics, Relativity, and Thermodynamics

Ian Shapiro, The Moral Foundations of Politics

Steven B. Smith, Political Philosophy

Cervantes Don Quixote

ROBERTO GONZLEZ ECHEVARRA

Yale

UNIVERSITY PRESS

New Haven and London

Copyright 2015 by Yale University.

All rights reserved.

This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers.

Man Carrying Thing, from The Collected Poems of Wallace Stevens by Wallace Stevens, copyright 1954 by Wallace Stevens and renewed 1982 by Holly Stevens. Used by permission of Alfred A. Knopf, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Random House LLC. All rights reserved.

Passages from Cervantes The Trials of Persiles and Sigismunda, translated by Celia Richmond Weller and Clark A. Colahan (Cambridge: Hackett, 2009), are reprinted by permission of Hackett Publishing Company, Inc. All rights reserved.

Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational, business, or promotional use. For information, please e-mail (U.K. office).

Set in Minion Pro type by Newgen North America, Austin, Texas.

Printed in the United States of America.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Gonzlez Echevarra, Roberto.

Cervantes Don Quixote / Roberto Gonzlez Echevarra.

pages cm. (Open Yale courses series)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-300-19864-5 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Cervantes Saavedra, Miguel de, 15471616. Don Quixote. I. Title.

PQ6352.G65 2015

863'.3dc23

2014031674

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.481992 (Permanence of Paper).

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

To my Yale College students,

for and with whom this course was created

Contents

Preface

This book was originally a lecture course for Yale undergraduates, which I have offered for many years through the Literature Major (Comparative Literature) and the Department of Spanish and Portuguese. This accounts for its containing some information that Hispanists in particular will find to be of an introductory nature. It also explains its occasional avuncular tone, which I tried to eliminate in the revision but traces of which inevitably remain. In my commentaries on Cervantes, however, I have endeavored to offer original insights; new slants on his life and works and even daring fresh interpretations. Yale undergraduates are sharp and willing to experiment, and I try to find ways of making accessible even the most complicated approaches, in the classroom and in my critical and scholarly work. Obscure critical jargon is not my style. I hope the general reader, to whom this book is aimed, finds my commentaries and arguments informative, illuminating, and compelling. I trust there is enough innovation in the book that I should not be embarrassed by specialists reading it.

Cervantes scholars will soon discover that I often summarize and even quote verbatim some of my earlier work on the Quixote and The Exemplary Novels, particularly from my Love and Law in Cervantes but also from my Cervantes Don Quixote: A Casebook. I could not do otherwise; my teaching and scholarship are intimately intertwined, feeding off one another. Besides, I feel that in glossing my own work I am not just repeating it but refining it.

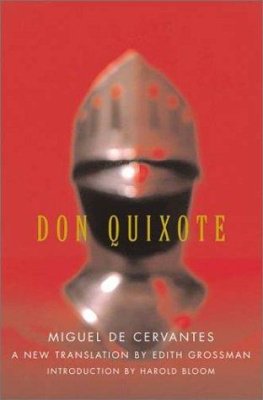

I have used John Rutherfords translation in the Penguin Classics edition with some resignation. It is good enough and it is prefaced by my introduction, which I naturally prefer to those of others. There is no exceptional translation of the Quixote. My favorite is Tobias Smolletts because he was a writer, not a former or current literature professor. But Smolletts somewhat archaic tone may put off some contemporary readers. Much is lost in the translations, anyway; first and foremost the contrasts between the speech of Sancho and other lower-class characters and that of Don Quixote. Cervantes is a virtuoso of dialectal forms. In any case, I am not a reader of translations, except when there is no alternative, as with the Greek classics and the Russian novelists. I have devoted a lifetime of work to be able to read with ease all the major works in the Romance languages, particularly French and Italian but also Portuguese and others, in the original. I am not a believer in Jorge Luis Borgess quip about translations sometimes being better than the original texts. I do not think he believed in it either. He labored hard to read the Icelandic sagas in their language, and he was quite proficient in (at least) English, French, Italian, and German.

My native and dominant language is Spanish, and I consider myself part of the critical and prose tradition of that language, in which I have published not a small amount of scholarly work, essays, and some journalism. I am Cuban, therefore a Latin American, and since my childhood as a faculty brat I have been surrounded by Spanish and Latin American literature. The reader of this book may find traces of this determining linguistic foundation in my American English. I am not a Spaniard, however, though Spain has become for me like a second motherland, and I have often taught, lectured, and lived in Spain, for the most part in Madrid and Salamanca. What this means is that I have a perspective on Cervantes that is from within his language but not from inside the nationalist obsessions that have beset criticism of his works since the eighteenth century. I am happy to report that this trend has abated in the recent past, but also unhappy to report that Cervantes is not read much in Spain anymore, particularly in the schools and by young people.

I have read and corrected the transcriptions of the lectures that make up this book, trying to prune as much of the personal inflections as possible. I have cut out anecdotes, a few jokes, asides, and other matters that the reader will not enjoy, although I hope my students did in the classroom. A course, I realize now more than ever, is very much influenced by the personality of the professor, who with his rhetoric and body language establishes communication with the students in a way that cannot be captured on the printed page or even in a videotape. This is why I believe there is no substitute for the classroom when it comes to education, particularly in the humanities. But the Open Yale Courses and other projects at various institutions are valuable approximations that have the virtue of reaching many people all over the world. I receive countless e-mails from individuals in faraway places who have followed my course.

Next page