Contents

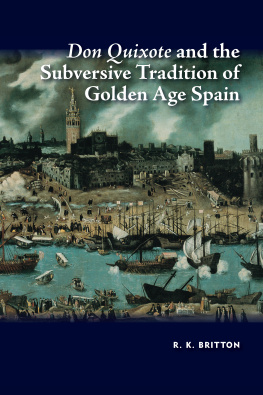

Don Quixote and the

Subversive Tradition of

Golden Age Spain

Don Quixote and the

Subversive Tradition of

Golden Age Spain

R. K. BRITTON

Copyright R. K. Britton, 2019.

Published in the Sussex Academic e-Library, 2019

SUSSEX ACADEMIC PRESS

PO Box 139, Eastbourne BN24 9BP, UK

Distributed worldwide by

Independent Publishers Group (IPG)

814 N. Franklin Street

Chicago, IL 60610, USA

ISBN 9781845198619 (Cloth)

ISBN 9781845198626 (Paperback)

ISBN 9781782845744 (EPub)

ISBN 9781782845751 (Kindle)

ISBN 9781782844921 (Pdf)

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purposes of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This e-book text has been prepared for electronic viewing. Some features, including tables and figures, might not display as in the print version, due to electronic conversion limitations and/or copyright strictures.

This study offers a reading of Don Quixote , with comparative material from Golden Age history and Cervantes life, to argue that his greatest work was not just the hilariously comic entertainment that most of his contemporaries took it to be. Rather, it belongs to a subversive tradition of writing that grew up in sixteenth-century Spain and which constantly questioned the aims and standards of the imperial nation state that Counter-reformation Spain had become from the point of view of Renaissance humanism.

Prime consideration needs to be given to the system of Spanish censorship at the time, run largely by the Inquisition albeit officially an institution of the crown, and its effect on the cultural life of the country. In response, writers of poetry and prose fiction strenuously attacked on moral grounds by sections of the clergy and the laity became adept at camouflaging heterodox ideas through rhetoric and imaginative invention. Ironically, Cervantes success in avoiding the attention of the censor by concealing his criticisms beneath irony and humour was so effective that even some twentieth-century scholars have maintained Don Quixote is a brilliantly funny book but no more. Bob Britton draws on recent critical and historical scholarship including ideas on cultural authority and studies on the way Cervantes addresses history, truth, writing, law and gender in Don Quixote and engages with the intellectual and moral issues that this much-loved writer engaged with. The summation and appraisal of these elements within the context of Golden Age censorship and the literary politics of the time make it essential reading for all those who are interested in or study the Spanish language and its literature.

Cover illustration : Vista de Sevilla, attributed to Alonso Snchez Coello (15321588). Reproduced with the kind permission of the Museo de Amrica, Ministerio de Educacin, Cultura y Deporte, Madrid, Spain.

R. K. Britton is an honorary research fellow in the Department of Hispanic Studies, Sheffield University, where he is also a part-time tutor in Spanish in The Institute of Lifelong Learning. His research interests are modern Latin American literature, the literature and culture of Golden Age Spain and literary translation. His The Poetic and Real Worlds of Csar Vallejo (18921938) was widely reviewed: Bob Brittons book brings Csar Vallejo fascinatingly to life, Adam Feinstein, author of Pablo Neruda: A Passion for Life.

Contents

Preface and Acknowledgements

Not long ago, I made an informal enquiry to a well-respected British university press in a city, whose name, at this moment, I choose not to recall, about whether it would be interested in a proposal for a book on Cervantes and Don Quixote that I was writing. The voice of the editor at the other end of the telephone hesitated before she replied: Cervantes?... mmmmm,... Don Quixote ?... There is rather a lot out there already you know. I pursued the matter no further.

In this respect, she was quite right. There is a lot out there. More than on any other single text probably, except for the Bible and the Koran. And Don Quixote is still only four hundred years old! Nevertheless, why should any sensible twenty-first century reader bother to plough through nearly a thousand pages of a story written four centuries ago? One answer may lie in the astounding amount of critical and academic baggage that this book, now hailed as the worlds first modern novel, brings with it. This intimidating body of work reveals the very considerable changes in approach and interpretation that different generations of scholars and critics have brought to the task of interpreting this amazing text, which seems to offer to each one a different key facet of itself that has previously been overlooked or underestimated. It is, perhaps, the nature of great art that it can be reconstructed, or reconstruct itself, so as to speak directly to each new and changing audience, but Don Quixote seems to have served not only as a mirror that reflected the face of sixteenth and seventeenth century Spain, but also one in which succeeding generations recognised themselves.

To briefly illustrate this point, there is a great deal of evidence that in seventeenth and eighteenth century Europe, notably in Spain, France and England, Don Quixote was regarded simply as a funny, entertaining book in which the reader did not seek for human and moral complexities or historical judgements. Later critics saw things differently however. For the Romantics the mad knight of La Mancha became a tragic symbol of the failure of heroic idealism in a material and corrupt world; for the Generation of 1898, he became an allegory of Spains loss of national vision which led to its decline from an imperial world power to a national backwater stifled by tradition. By the 1920s, this view began to be rejected (along with symbolism and modern allegory) in favour of one that saw Don Quixote as essentially a product of its own age and circumstances, which could only be understood from a historicist standpoint. New biographical studies of Cervantes, based on fresh documentary evidence, also began to appear so that the figure of the historical Cervantes, as distinct from the writer who hid behind a variety of literary masks, began to emerge. Furthermore, it did so against a more detailed and certain backdrop of the social history of Spain under Hapsburg rule.

The picture was further influenced by changing intellectual tastes and fashions derived from recent disciplines, such as psychology, sociology and linguistics, together with the evolution of traditional ones such as history, politics and economics. The twentieth century also saw the emergence of Critical Theory and a varied current of sophisticated, forensic literary scholarship that has become an integral part of university education in the arts and humanities in Western Europe and the USA. Indeed, if we now ask who the twenty-first century readers of Cervantes masterpiece are likely to be, the answer is certainly in the so-called developed countries that they will mostly be people who have passed through a system of mass higher education, extending to some 40 percent of the national population. This, I suggest, marks the emergence of a new kind of reader for all kinds of literature, but for old books it is especially important. The educated reader of today the precise equivalent of what Cervantes referred to as the lector discreto (the reader of good judgement) of his own time is likely to bring to the task, and to a degree that would have been rare in the past, a new sense of history, a keen awareness of the cultural diversity of the world, and at least some of the specialist tools of critical appreciation honed in todays universities degree courses.