SPAIN

SPAIN

The Centre of the World 15191682

ROBERT GOODWIN

For Clare

Happy age, and happy days were those, to which the ancients gave the name of golden; not that gold, which in these our iron-times is so much esteemed, was to be acquired without trouble in that fortunate period; but because people then were ignorant of those two words MINE and THINE: in that sacred age, all things were common... All was then peace, all was harmony, and all was friendship.

Don Quixote

Contents

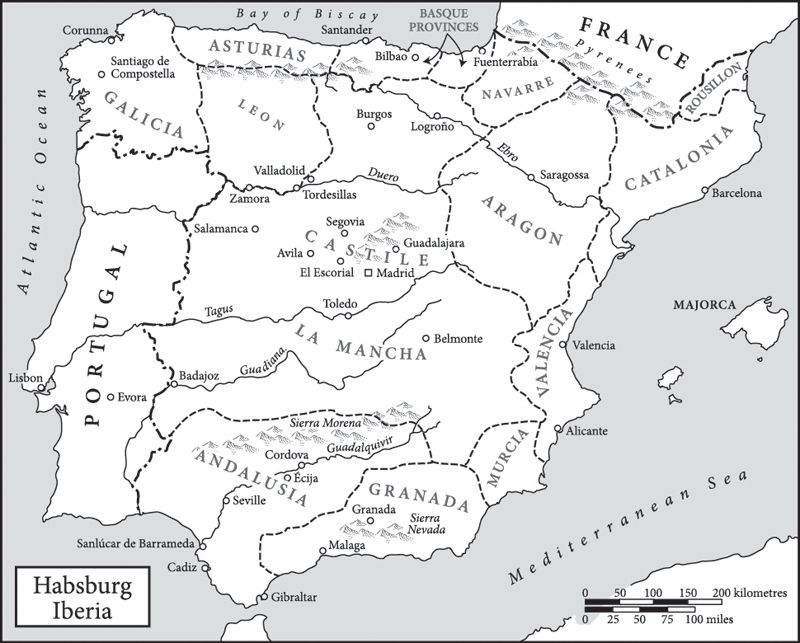

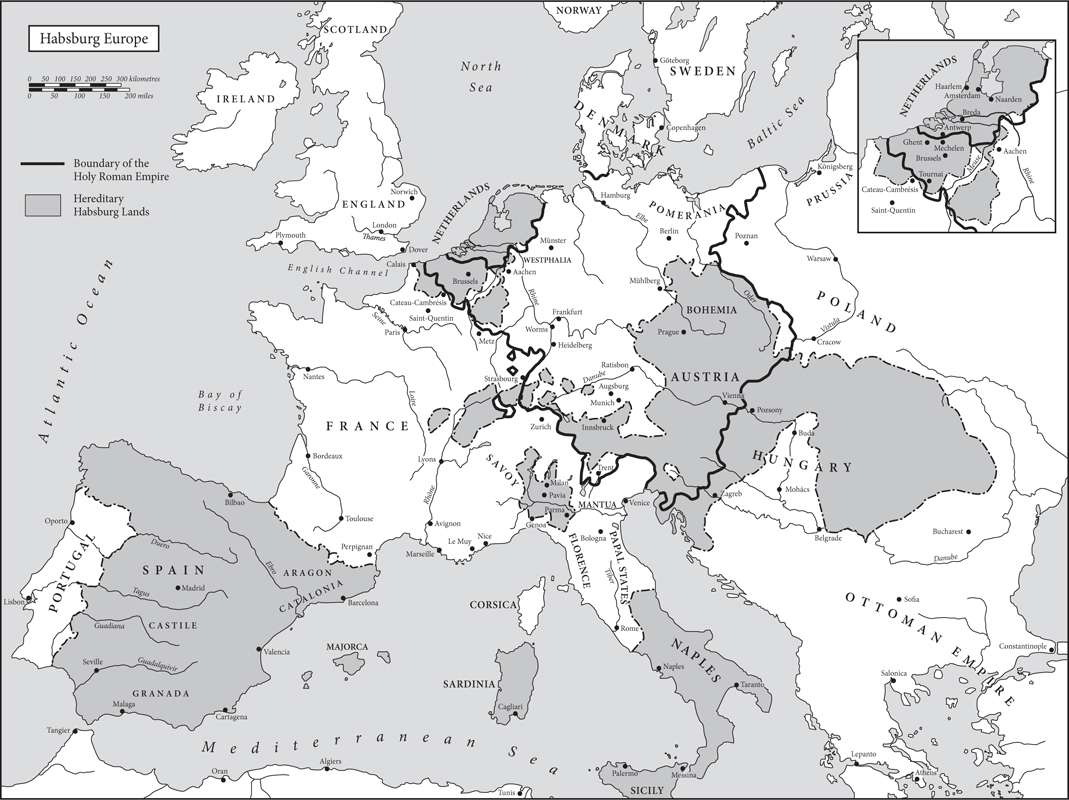

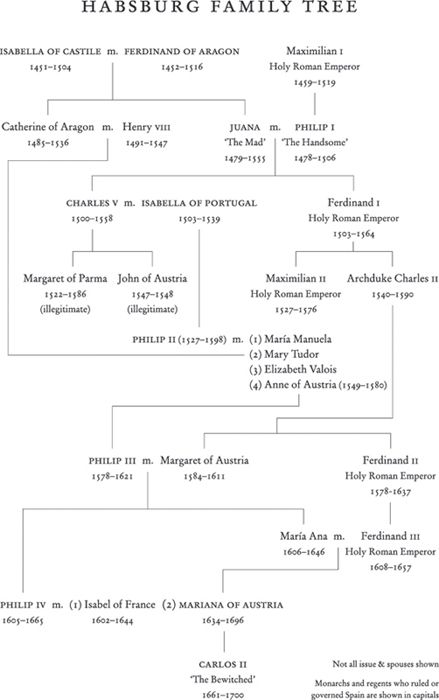

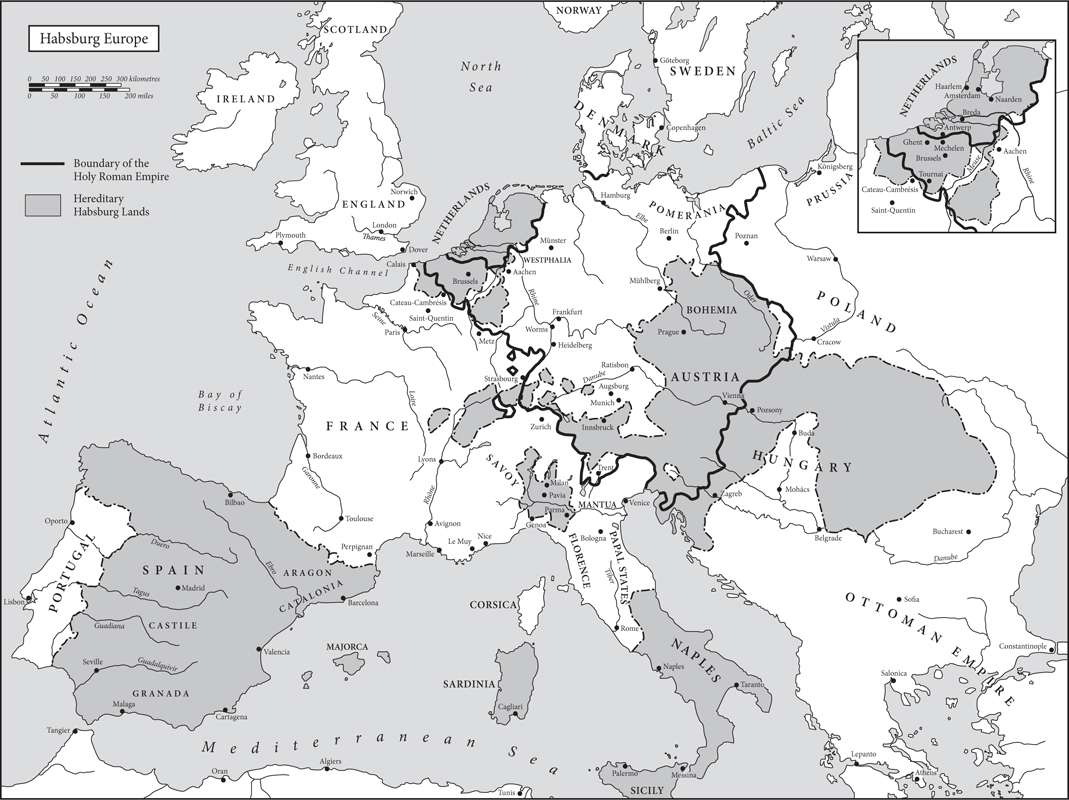

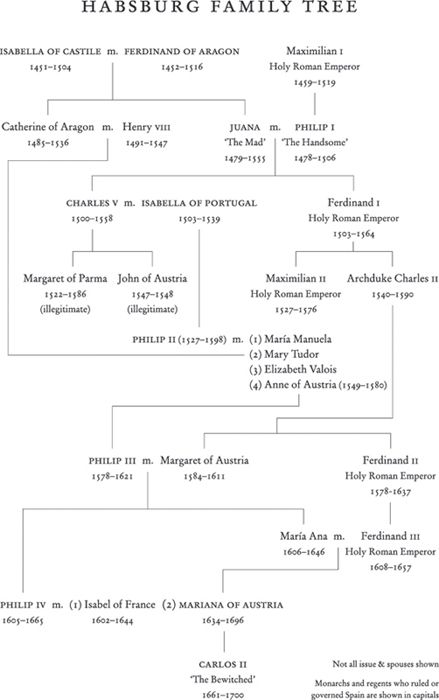

At the beginning of the modern era, Spain became the centre of the western world by accident. In 1492, Columbus discovered the Americas while searching for a route to Asia across the Atlantic and claimed the New World for his Spanish sponsors. Then Charles of Ghent, born in 1500 to a Spanish mother and a Burgundian father, because of a series of marriage alliances and untimely deaths became heir to three of the most powerful royal and princely houses of Europe and a host of other lands and titles. As he grew to adulthood he inherited vast domains in the Netherlands, Burgundy, Italy, Austria and Hungary; and as the future head of the House of Habsburg he was brought up to believe in his moral right to rule the Holy Roman Empire, encompassing most of modern Germany and more. In 1517, at the age of seventeen, he left his native Flanders to claim the thrones of Castile and Aragon, the two great crowns of Spain, and with them the Kingdom of Naples and all of Spanish America. For the next century and a half, the Habsburg dynasty made Spain the economic and military centre of its world, the heart of the first global empire on earth.

In Spain: The Centre of the World 15191682 I have tried to tell that epic history through the stories of two dozen emblematic Spaniards and their monarchs. Biographical anecdote, humour and moments of high drama, dudgeon and low bathos offer an intimate and familiar foreground from which to appreciate the enormity, both in time and space, of the history of Habsburg Spain. There are many magisterial textbooks on the subject, as Spaniards say, but these necessarily contain almost overwhelming amounts of scholarly detail for the general reader, filled with names and dates and places and events, often managing only occasional and fleeting moments of human contact. So, while this piece of storytelling properly belongs alongside them, it is not really of their ilk. This is a book for you, idle reader, as the great Spanish novelist Miguel de Cervantes described you in his introduction to his most important work, Don Quixote, addressing the newly literate reading public of his age, purchasers and consumers of the written and then printed word who forged the tradition which you have inherited and will pass on.

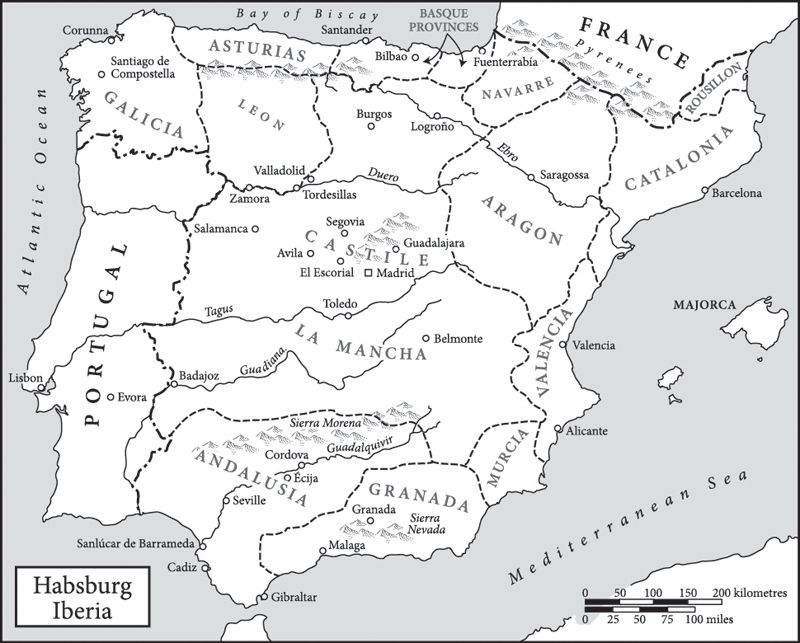

In the early 700s, Muslim armies from North Africa conquered and occupied almost all Spain. Only one chieftain held out against the Islamic invader, Pelayo, leader of a small band of indomitable Christians in the far north. For the next eight centuries, Iberian history was dominated by the slow emergence of the kingdoms of Portugal, Castile and Aragon, as the peninsula was slowly won back by Christian crusaders and opportunist frontiersmen. By the late fifteenth century, that Reconquista or Reconquest was almost complete and, instead, civil war threatened to destroy Christian Spain as the great aristocratic houses lined up their private armies during a succession crisis in Castile. But the marriage of Ferdinand, heir to the throne of Aragon, to Isabella, Queen of Castile, in 1476, proved a powerful alliance, strong enough to force peace upon their unruly subjects; and they sealed this new, fragile sense of unity by announcing a final crusade against Granada, the last Islamic kingdom on the Iberian Peninsula. The Spanish nobility and many foreign aristocrats from across Christendom answered that call to arms and in January 1492 Isabella and Ferdinand, for ever to be known as the Catholic Monarchs, marched victorious into Granada at the head of their army; Boabdil, the last Muslim ruler in Spanish history, stopped at a mountain pass and looked back for one final glimpse of his erstwhile paradise, and he wept; the place is still called the Moors Sigh.

In the euphoric aftermath of victory, the Catholic Monarchs further embraced the current crusading spirit of religious intolerance by ordering the expulsion of all Spanish Jews. They also sent Christopher Columbus to sail to China and India by an Atlantic route; and his accidental discovery of the Americas enabled Spain to become the centre of the world for almost two centuries. But, following the death of Isabella in 1506, Ferdinand, as King of Aragon, had no right to rule in Castile; the crown should have passed to his daughter, Juana, the tragic figure always known in English as Joan the Mad, who was married to Philip the Handsome of Burgundy. Their eldest son was Charles of Ghent, their youngest was named Ferdinand after his grandfather. But when Philip died suddenly, soon after arriving in Spain to claim the throne, Ferdinand, the wily old Catalan, seized power, declaring Juana incapable of rule because of her insanity. The veteran monarch reigned until his death, in 1516, when the young Charles of Ghent, Lord of the Netherlands, Count Palatine of Burgundy, inherited the crowns of Castile, Aragon and Naples, and was proclaimed the King of Kings.

During the sixteenth century, the Spanish Habsburgs defended and expanded their vast Empire, which stretched from the distant east and south of Europe to Goa and the Philippines, to Chile and New Mexico. That imperial story forged the character of Spain and the Spaniards who were the heart and lifeblood of the enterprise. They went to the Americas as conquistadors and settlers, they campaigned across Europe as feared professional soldiers, they travelled as merchants and diplomats, poets and artists. Seville, the great inland southern port, became the centre of world trade, a place of foreign merchants, bankers and adventurers, all drawn to Spain by the contagious magnetism of possibility and the vast quantities of American gold and silver which poured into the kingdom. The Habsburgs and the Spaniards were, hand in hand, in the ascendant politically and militarily across half the world; at home, those fierce tensions between Crown and state, between aristocracy and urban oligarchs, between town and country, between Church, peasant and landlord, balanced one another in a dynamic equilibrium from which emerged great institutions such as universities, schools, the rule of law, banking and local government, and which fostered arts and letters, all underpinned by the severe moral authority of a newly militant Church. It was an era of great optimism and self-confidence.

Then, during the seventeenth century, Spaniards found themselves overstretched and damaged by foreign wars and ruled by decadent monarchs and their venial favourites. Slowly, the world Empire began to come apart. The Spanish Habsburgs lost control of their ancestral lands across Europe, from Portugal to Catalonia and from Italy to the Netherlands, and they lost important possessions overseas as well. The Spanish Crown and its government also suffered and the Habsburgs lost power and influence at home. Yet this period when the monarchs and their state institutions went into sharp decline was also a time of dazzling artistic and literary production in Spain and in many ways Spaniards seem to have flourished in stark contrast to the decadence of their government. The sickness of the Spanish state has, perhaps, proved little more than a carapace which has long obscured historians views of the dynamic nation beneath.

Next page