Godfrey Goodwin

The Private World of

Ottoman Women

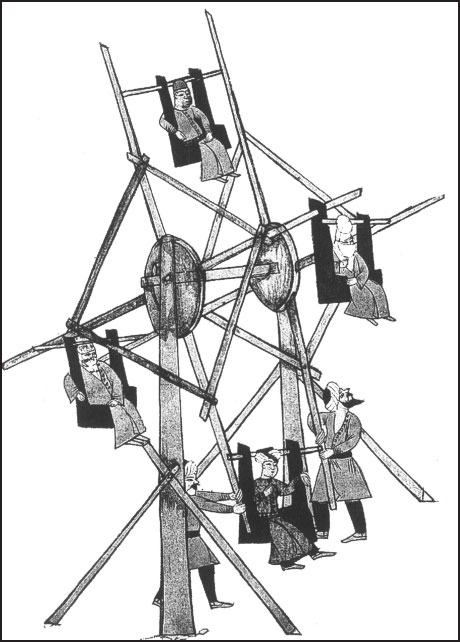

Women having fun on the Great Wheel, early seventeenth century (F. Taeschner, Alt-Stambuler , Hanover, 1925)

I shall die this autumn. My tasks are finished now

I have washed in the brook, climbed the walnut-tree, frightened birds

Been kidnapped. Born twelve children. Cradled, watched

Married a son, lost a daughter, lived to be thirty.

From Autumn by the female Turkish poet Glten Akn (b. 1933). Translation by Nermin Menemenciolu (from The Penguin Book of Turkish Verse, edited by N. Menemenciolu).

Illustrations

Harem girl in the early nineteenth century in front of the palace at Saadabad at Kaithane (the Sweet Waters of Europe) at the top of the Golden Horn (Sotheby, 1984)

A Note on Pronunciation

The spelling adopted here is based on modern Turkish but I have even taken liberties with that. All Turkish letters are pronounced as in English except for the following:

c pronounced j as in jam

pronounced ch as in child

not pronounced; lengthens the preceding vowel

akin to the pronunciation of u in radium

pronounced as in the German Knig

akin to the sh in shark

pronounced u as in the French tu

Acknowledgements

This book was born of many invaluable conversations, including those with the late Mme Emin Pasha, the late Aliye Berger-Boronai and the late Princess Fahrlnissa Zeyd-l-Huseyn, among other members of the akir Pasha family. irin Devrim is still very much alive. The sections on costume owe much to the authoritative publications of Dr Jennifer Scarce from whose works I do not quote directly; indeed, she may feel that she had no influence at all.

It would be impossible to list all the Turkish women and men who have helped me with information, nor can I include all the people who, although not Turkish, have a deep knowledge of the country. They include: Dr Sina and Tulin Akin, Professor Glen Akta, the late Bay Tahir Alangu, Professor Metin And, Professor R. Ark, Professor Nurhan Atasoy, Professor Esin Atl, Mrs Dorin Axel, Dr Margaret Bainbridge, Professor Oya Baak, Professor Michele Bernadini, Professor Faruk Birtek, Lady Burrows, Dr Filiz aman, Dr Cevat Capan, Professor John Carswell, Lady Daunt, the late Bay Emin Divan-Kibrizli, Elmas Hanm, Dr Jale Erzen, Andrew and Dr Caroline Finkel, Mrs Minnie Garwood, Bayan lin Glensoy, Professor Haldun Grmen, Professor Fahir z, Professor zer Kaba and the sadly missed late Ayma Kaba, Mrs Evelyn Kalas, Dr Denise Kandioti, Professor Cemal Kavadar and Professor Glru Necipolu, Professor Geoffrey and Mrs Lewis, Mrs Arlette Melaart, the late Mrs Nermin Menemenciolu-Streeter, Mr Sedat Pakay, the late Mehmet Ali Pazarba, Dr Helen Philon, Professor Andr Raymond, Professor J. M. Rogers, Bayan Kereme Senycel, Dr Ezel Kural Shaw, in particular the late Dr Susan Skilliter, Bay Artun nsal, Mrs Gillian Warr, Bay Bal and Angela Yazc.

I have to thank Bayan Mary Berkmen for her hospitality and support and the librarians of Boazc niversitesi; Michael Pollock, Librarian of the Royal Asiatic Society in London, and its conservationist Graeme Gardiner; the staff of the British Library; and, in particular, Dr Tony Greenwood, Director of the American Research Institute in Arnavutky.

My wife has been an invaluable critic and has survived the intrusion of the manuscript into her life.

As always, my publisher Andr Gaspard has been continually protective and encouraging while Jana Gough has again been the most humane of editors. With this book she has taken quite exceptional pains and I am deeply indebted to her.

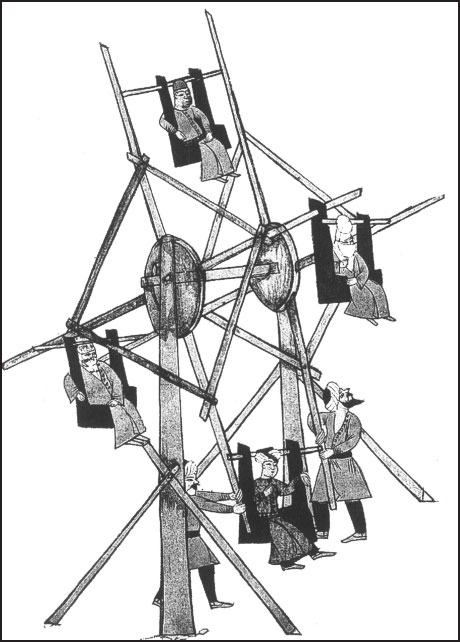

The Wedding (F. Taeschner, Alt-Stambuler, Hanover, 1925)

Foreword

We Must Walk Where No Aircraft Flies

It is important to make clear from the start that the great problem in writing this book has been the paucity of letters by Turkish women, let alone diaries. I have therefore had to resort to contemporary accounts these are mainly by European travellers who were often poor or spasmodic witnesses. There is, however, another source: the growing evidence gathered and evaluated by modern economic and social historians such as Inalck and Faroqhi in particular.

The scope of the book has been restricted else it would have grown out of all proportion. It is for this reason that Syrian and Egyptian women have been ignored: although, strictly speaking, they were Ottomans for several centuries, they belong to their own respective cultures. I also decided to stop at 1924 when Atatrk founded the Republic. The period requires a second volume in which to record the achievements of women in the last seventy years. Nor would I be able to write it. It is for that reason that the book is restricted to the period of the sultanate. Even this has had to be cut ruthlessly because the Ottoman empire nurtured many disparate societies.

Anyone who has lived and travelled in modern Turkey, and who cares a jot for the human race, can only be impressed by the hardship of village life even today. This includes that of the extended villages which form the suburbs of cities and towns. For a great many people, life is a condition that must be endured. Yet there are moments of relaxation, of pleasure and of festivities while the earth still bears fruit, however grim the future may be with the dwindling harvests from forests and sea. It is gossip which keeps a community alive that great game that notices the slightest gesture that is out of place, hesitation before a familiar door, the late arrival at the washing place that is the club to which all village women belong. It comes from acute observation and a shared store of knowledge beside which the skills of poker, bridge and meddling with micro-chips appear singularly commonplace.

The Republic legalized the liberation of women in spite of all the prejudices nurtured through generations which recede into the dark ages before recorded history. Women now direct major museums and are professors in the universities. They are beginning to be a force in the politics of the democracy. This change from the past to the future is not confined to the educated but is perceptible among the young in spite of reaction and this heartens older generations who battled for liberation. It should be remembered how recently equality for women has evolved in the richer countries of Europe and America. Even today, a woman has never been elected president of the United States or appointed editor of a great newspaper. Such things will come.

It is important to recognize that the nineteenth century was just as much a period of social and political turmoil in Istanbul as it was in the rest of Europe. It did not come to the rescue of Ottoman women immediately but the first schools for girls bred the first suffragettes. It was to be long before the villager could enjoy the privilege of reading and writing. Besides the schools, a secret revolution occurred when governesses came into fashion among wealthy families. These women came from England, France and Germany, sometimes all at the same time. Some were not very clear in their own minds about the future of women as they saw it. They were unlikely to evangelize their charges except by osmosis and by endowing them with the eye-widening pleasures of commanding several languages and their imported cultures.

![Goodwin - Fatal colours : the battle of Towton, 1461 ; [Englands most brutal battle]](/uploads/posts/book/98484/thumbs/goodwin-fatal-colours-the-battle-of-towton.jpg)