Steven Richmond received his doctorate in Russian history from the University of Chicago in 1996. He taught history in Istanbul, Turkey for more than ten years. He is presently a Research Fellow of the Netherlands Institute in Turkey, and an Associate of the Center for Middle Eastern Studies at the University of Chicago.

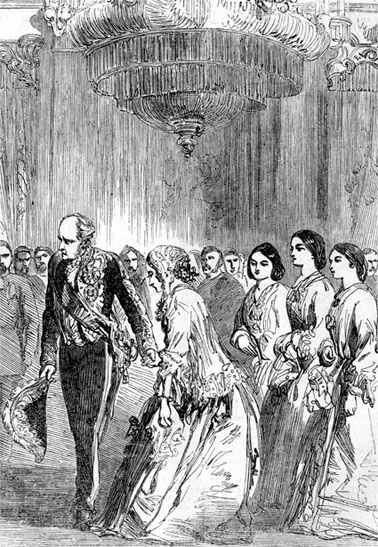

Stratford and Eliza Canning and their daughters Louisa, Catherine and Mary, in the ballroom of the British Embassy at Constantinople, 15 December 1854.

Published in 2014 by I.B.Tauris & Co Ltd

6 Salem Road, London W2 4BU

175 Fifth Avenue, New York NY 10010

www.ibtauris.com

Distributed in the United States and Canada

Exclusively by Palgrave Macmillan

175 Fifth Avenue, New York NY 10010

Copyright 2014 Steven Richmond

The right of Steven Richmond to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or any part thereof, may not be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Library of Ottoman Studies 35

ISBN: 978 1 78076 117 6

eISBN: 978 0 85773 387 0

A full CIP record for this book is available from the British Library

A full CIP record is available from the Library of Congress

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: available

Typeset in Garamond Three by OKS Prepress Services, Chennai, India

To my parents

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

During my years in Istanbul I often visited the sites of the story recounted here. They include Pera, present-day Beyolu, the first and greatest diplomatic quarter in history; Topkapi Saray, the wondrous inner sanctum of Ottoman power, still rarely seen by foreigners through the beginning of the nineteenth century; and the Bosphorus, both worldly in its meaning and ethereal in its beauty, a double bridge east-west by land and north-south by water.These and other impressions gained by personal contact with the scenes of history were essential to the study presented here. My exploration of Istanbul was inspired by Dolores and John Freely, F.Cenan Kocares_it, Emin Saatc_iand Ferdinand Schirza.

The Netherlands Institute in Turkey, with which I have been affiliated as aResearch Fellow, provided me with ascholarly home in Istanbul, ahaven for research, composition and the interchange of ideas. I am grateful to the staff of the Institute and especially to its director, Fokke Gerritsen, for arranging my status there. I am grateful also to Onno Kervers, Consul General of the Kingdom of the Netherlands in Istanbul, for his commentary on my Glossary of Diplomatic Terms.

In Istanbul I was helped in many ways that were vital to this study by Ekrem Ekinci, Melvin Kenne, Susan Nemazee and Peter Westmacott, Cneyd Okay, Ian Sherwood, Victoria Short, Mary Ann and Benjamin Whitten, and Tuncay Zorlu.

An academic sabbatical granted by Istanbul Technical University for the summer and autumn 2009 semesters enabled me to spend six months as avisiting scholar in the Department of History of the Faculty of Arts and Humanities, The School of Oriental and African Studies of the University of London. I am grateful to Benjamin C. Fortna, then head of the Department of History at SOAS, for arranging this status.

I conducted other research visits to London each year from 2006 to 2011 during my university intersessions, and these were all made possible by the hospitality of Thomas Short, Susan Spindler and Peter Brown, Caroline and Andrew Finkel, and Michael Riley. In England Iwas helped in many ways by Mark Bertram, Danielle Doran, Helena Drysdale, Kathryn Ward Dyer, Elizabeth, Priscilla and Giles Hunt, Briony Llewellyn, Betty Whittall and Paul McKernan, Bobbie Brookes Nation, Charles Newton, Lois and David Sykes.

I am additionally grateful to Peter Brown and Giles Hunt for their commentary on many parts of the text.

My editors at I.B.Tauris of London, Lester Crook and Tomasz Hoskins, were professional and patient with my work, and I am grateful to Tomasz for our many discussions concerning the production of the book. I benefitted also from the thoughtful examination of my text that was undertaken by the publishers academic reader.

In the United States of America I was helped in many ways concerning this study by Wayne Altree, Carel Bertram and Fred Donner, Patricia McKelvey and Eugene Putala.

MAPS

Pages 19-21

from William Miller, The Ottoman Empire, 1801-1913.

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1913.

from J. G. Bartholomew,ed. Handy Reference Atlas of the World.

Seventh Edition. London: John Walker Co. Ltd., 1904.

Adetailfrom The Dardanelles andthe Troad. The Bosphorus and

Constantinople, map by Stanfords Geog. Establishment. [Early1920s].

Illustrations

Stratford and Eliza Canning and their daughters Louisa, Catherine and Mary,inthe ballroom of the British Embassy at Constantinople, 15 December 1854. From adrawing, The Illustrated London News, 13 January 1855, page 33.

Yedi Kule, the Ottoman fortress of Seven Towers. From adrawing, The Illustrated London News, 24 September 1853, page 272.

Bb-i Hmyn, the Imperial Gate of Topkapi Saray. From adrawing, The Illustrated London News, 3 August 1850, page 105.

INTRODUCTION

THE STRATFORD LEGEND

Stratford Cannings journey to the Ottoman Empire is a story of his time, a representation of the increased mixing of distant peoples which emerged over the first half of the nineteenth century. The advent of steam travel in the 1820s and 1830s and of the telegraph in the 1850s radically affected communication in both voyage and post. These and other innovations transformed many fields of human relations, and Cannings long career spanned fundamental changes in the practice of diplomacy

For 50 years Stratford Canning kept returning to Constantinople

This study of Stratford Canning and diplomacy with the Ottoman Empire is designed to convey both what and how things happened what diplomacy was like at that time, how things occurred, what the atmosphere was like, and what the people were like, as George F. Kennan, the diplomat-scholar, described the ambition of his own books.

When Sultan Abdlmecit issued significant reforms concerning religious tolerance on 21 March 1844, Stratford Canning was extolled in British newspapers as the Reformer of Turkey and even credited with the most remarkable diplomatic achievement in the annals of Turkey.

But Stratford Canning certainly did not reform the Ottoman Empire. No foreign representative could ever do anything like this for the state to which he was accredited. The reform movement of the Ottoman Empire was home-grown and comprehensive. It was indigenous to Ottoman history. It was conceived and enacted by Ottoman statesmen. And it began to take course before Stratford was even born. His career happened by chance to coincide with the rise of this movement and Stratford Canning supported the reform party with characteristic energy and vigour, according to his protg and long-time associate, Austen Henry Layard, the excavator of Nineveh.

Cannings support for Ottoman domestic reform, as well as for Ottoman international peace, was not inspired by sentiment for the country or its peoples (although he was on many occasions throughout his career motivated by genuine humanitarian concern, and he did after a certain point see his relationship to the Ottoman Empire in something of a missionary light). Rather, it was purely a calculation of British foreign policy relating to the so-called Eastern Question.